The picture is firming up, and it’s devastating. Six people are dead at the foot of Mount Maunganui because, over four critical hours on the morning of 22 January, New Zealand’s emergency management system failed. Not just failed, but failed repeatedly, in ways that now look systemic. And what’s becoming clearer with each new revelation is that this wasn’t just bad luck or an unforeseeable tragedy. This was a disaster waiting to happen, built on decades of complacency, underfunding, and a dangerous habit of ignoring what geologists have been telling us.

The timeline alone is damning.

Around 5am, Lisa Maclennan woke to find her campervan had been shoved forward by a slip. She spent the next hours desperately trying to raise the alarm – knocking on doors, waking campers, trying to reach camp staff. No one was at the office. The emergency number went unanswered.

At 5:47am, local man Alister McHardy called 111. He’d seen multiple slips near the campground and was worried about people below. Fire and Emergency told him it was “more a council matter” and said they’d notify Tauranga City Council. They did (at 5:51am) but here’s where things get truly alarming. The call went to the Council’s Contact Centre, not its Emergency Operations Centre, and the message did not got through to the appropriate people. That distinction, as Andrea Vance points out in The Post today, “may become critical. It already exposes gaps in how life-or-death information is recorded, escalated and acted on.”

At 6:18am, another camper called Police. She spoke to them for eight minutes. She told them a slip had pushed a campervan about a metre forward. Police said they’d try to send someone. No one came.

Around 7:42am, the campground manager and a Council worker drove through the site in a golf buggy. Campers pointed out the slips. The staff looked at them, then drove off to check on the Surf Club. They never came back. Another Tauranga City Council ute drove through the campground around 7:45am, past three visible slips.

At 8:02am - more than three hours after the first warnings - the Council announced on social media that the mountain’s walking tracks were closed. Still no evacuation order for the campground directly below the unstable slope.

At 9:30am, the hillside came down. Six people died. Lisa Maclennan, the teacher who had spent the morning trying to save others, was one of them.

The Lies we tell ourselves about preparation

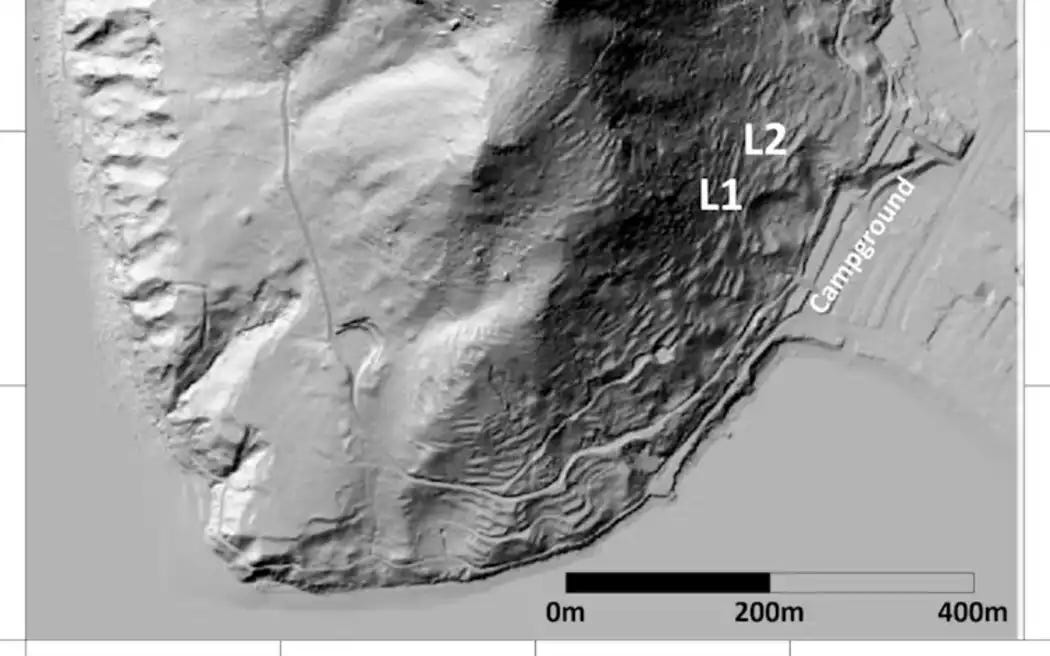

Mount Maunganui has a documented landslide history stretching back more than a century. A major slip occurred in 1977 in almost exactly the same spot. A 2014 scientific paper mapped landslides on Mauao back to 1943. As Vance notes bluntly: “This is not a freak event in an unknowable place. Mauao has a documented landslide history stretching back more than a century.”

Two decades ago, in 2005, geotechnical engineers told Tauranga City Council that buildings should not be allowed in the “runout zones” at the base of potential landslides unless specially protected. The runout zone is exactly what it sounds like: the area where debris from a slip will end up. The advice was stark: “Only in rare circumstances would it be prudent to violate” the zone criteria. Buildings shouldn’t be there. Full stop.

Yet in July 2025, when the Council commissioned WSP to do a comprehensive landslide susceptibility study using detailed terrain mapping, the hazard boundary stopped short of the holiday park. Why? The Council won’t answer, but it seems that tourists don’t get the same risk assessment as ratepayers. If you’re not paying rates, you don’t show up on the hazard map.

The mountain itself was used as the case study for the WSP report – it “clearly flagged the danger across Mount Maunganui” – yet somehow the campground at its base, full of vulnerable people in tents and campervans, fell through the cracks.

This is the bureaucratic logic that kills people.

New Zealand’s geological blindness

We are a nation obsessed with earthquakes, yet we are blind to our deadliest hazard: the earth beneath us giving way. The reality is that landslides have killed more people in this country than quakes.

Professor Martin Brook from the University of Auckland puts it plainly: “Most of New Zealand is under-researched from a geological standpoint.” Over the past 160 years, landslides have claimed between 700 and 1,800 lives, significantly more than earthquake deaths over the same period. GNS Science research shows landslides cause an average of three deaths per year and cost the country $250-300 million annually.

We’ve recently become sensitive to tsunami risk. Signs have gone up, evacuation routes mapped. But landslides, historically far more dangerous, have been largely ignored. Brook again: “The country had woken up recently to tsunami risk and signs and advice had sprung up, but had only begun waking up to the risk of landslides since 2023 though they were the country’s most deadly natural hazard.”

Why the blindness? Part of it is that landslides don’t come with the dramatic, single-event horror of an earthquake that brings down a whole city. They kill “one or two at a time, often in places people think are safe,” as disaster risk specialist Tom Robinson notes. The deaths accumulate quietly. No one particular disaster galvanises public attention or forces political action.

But there’s another reason, and it gets to the heart of what’s broken in New Zealand’s approach to managing natural hazards: we’ve systematically dismantled the expertise needed to make good decisions.

The Outsourcing disaster

David Buxton is a Northland geotechnical engineer. He benefits financially from the current system. And even he says it’s not working.

Since the 1990s, Buxton explained to RNZ, councils have been “shedding expertise” – getting rid of in-house geotechnical engineers and contracting the work out instead. The problem isn’t just that this is expensive. It’s that councils are now “reliant on outside advice” but also “reliant on in-house people without that depth of technical knowledge to make that decision-making.”

You end up with a situation where councils commission reports they don’t fully understand, written by consultants who leave once the job is done. There’s no institutional memory, no one with deep geological knowledge sitting in the room when crucial land-use decisions are made. The result, Buxton says, is “patchy follow-through.”

Auckland Council bucked this trend. It invested in in-house geotechnical expertise. That investment, Buxton notes, has been “paying off in its response to floods.” But most councils can’t or won’t make that investment, caught in a bind where central government keeps piling responsibilities on local government without providing the funding or regulatory framework to actually deliver.

Andrea Vance makes this point forcefully: “Nor should local government become the scapegoat. Councils are already underfunded and overburdened, carrying climate risk on balance sheets never designed for it.”

So when things go wrong, who gets blamed? Not the decades of policy decisions that hollowed out local government capacity. Not the successive central governments that refused to build a proper national framework for managing climate-amplified hazards. Instead, attention focuses on the Council worker who drove past the slip at 7:45am, or the dispatcher who said it was “a council matter.”

Those operational failures matter, absolutely. But they’re symptoms of a much deeper political failure.

The System that wasn’t there

One phrase keeps coming up in the commentary on Mount Maunganui: “common operating picture”. It sounds like jargon, but it points to something fundamental that New Zealand still doesn’t have.

Vance again: “New Zealand has still not built a common operating picture for disasters, despite warnings going back two decades, and most recently after Cyclone Gabrielle and the Auckland Anniversary floods.”

A common operating picture means that when someone calls 111 at 5:47am to report a landslide risk, that information doesn’t just get logged somewhere. It gets escalated. It reaches the people with the authority to order an evacuation. It connects the dots between what Fire and Emergency knows, what the council’s Contact Centre knows, what Police know, and what the people on the ground can see.

Instead, in New Zealand we have information silos. Fire and Emergency says they notified the Council. The Council’s chief executive initially claimed they had “no record” of the call, then backtracked and admitted the Contact Centre got it but the Emergency Operations Centre didn’t. The campground was left essentially unstaffed during a state of emergency. No one, it seems, had a clear picture of what was happening or the authority to act on it.

Jack Tame draws the parallel to Pike River: “Just as Pike River was a catalyst for huge health and safety law reforms, the Mt Maunganui disaster is fast shaping up as a watershed moment for property owners and councils around the country.”

Pike River killed 29 miners in 2010. The public outcry forced major changes to occupational safety law. Will Mount Maunganui do the same for emergency management and land use? It should. But that depends on whether the inquiry that follows has the teeth to look beyond the operational failures to the deeper policy choices that set the stage for this disaster.

The Inquiry question

Police have announced they’ll be looking into whether there’s criminal liability. WorkSafe is investigating whether organisations with a “duty of care” for the holiday park met their health and safety responsibilities. The coroner will conduct an inquest. Tauranga City Council has announced its own independent review.

But as Vance argues persuasively, a Council-initiated review can’t carry the full weight of what needs to be examined. “When the land, assets, data and decision-making all sit within the same organisation, true independence is structurally impossible.”

Central government also needs to be scrutinised. What happened to the $6 billion National Resilience Plan that Labour set up after Cyclone Gabrielle? The current Government wound it up in Budget 2024, returning $3.2 billion to the Crown. Finance Minister Nicola Willis said this was about putting spending through “normal Budget processes.” But as Vance asks: “How much of that reached hazard mapping, early-warning systems, or real-time information platforms?”

The Prime Minister has announced this afternoon that the Government is likely to launch its own official inquiry. That’s good. It should happen. But the “terms of reference” will matter enormously. Will it look at why Mauao wasn’t included in the WSP landslide study? Will it ask why the campground was never mapped as sitting in a runout zone, despite explicit advice two decades ago? Will it examine whether councils have the capacity – the funding, the in-house expertise, the legal framework – to actually manage these risks?

A government-level inquiry would have, as Vance says, “the power, resources and political distance to follow every thread, including the science, the maps, the warnings, the comms systems, the funding choices, and the response.”

Without that, we’re left with the usual pattern: a narrow operational review, a few scapegoats, some incremental procedural changes, and then back to business as usual. Until the next preventable disaster.

The Climate crisis we refuse to name

Adam Pearse, writing in the Herald, notes that Prime Minister Chris Luxon has handled the immediate emergency response well, alongside Emergency Management Minister Mark Mitchell, who has been “calm and confident.” But Pearse asks the harder question: “How Luxon delivers on what is one of the greatest threats facing this country will go a long way toward defining his own legacy as a leader.” He’s talking about climate policy.

So far, that answer isn’t promising. When pressed on climate adaptation, Luxon points to Climate Change Minister Simon Watts, who is working on a national flood map due in 2027. Meanwhile, New Zealanders are told to expect a bipartisan approach and trust that the Government is building resilience.

But what does that resilience building actually look like when you’ve dismantled a $6 billion resilience fund? When the National Adaptation Framework, released in October 2025, is heavy on process and light on urgency? When councils are expected to lead local adaptation planning but lack the funding, technical support, and regulatory framework to do so?

Climate scientist James Renwick has been making the same argument for years. Climate change isn’t making more storms necessarily, but it is “making the most extremes of weather more extreme.” Warmer air holds more moisture; when that moisture comes out, you get more intense rainfall. Tauranga recorded 198mm of rain in 12 hours on 21-22 January - two and a half months’ worth in half a day. That’s the new normal.

Dealing with climate change, Renwick says, isn’t a “cost to the economy” but an investment. If we don’t make it, “the future cost is going to be huge and, ultimately, it’ll be overwhelming. It will destroy our economy.”

Yet public sentiment is running well ahead of the politicians. A new poll reported today by Marc Daalder of Newsroom shows 54 percent think the Government should be doing more to tackle climate change. Only 20 percent rate the climate response positively. The most common feelings about the Government’s approach are concern, disappointment, and frustration. It seems that the gap between what the public wants and what successive governments are delivering has never been wider.

What Happens next

The families of the victims deserve answers. Lisa Maclennan, Måns Loke Bernhardsson, Jacqualine Wheeler, Susan Knowles, Sharon Maccanico, and Max Furse-Kee died because the system failed them. They deserve to know why.

But this goes beyond six deaths at a campground in Tauranga. This is about a country that has spent decades ignoring what its geologists have been saying. That has systematically defunded and deprofessionalised local government. That still, after Cyclone Gabrielle, after the Auckland floods, after decades of warnings, doesn’t have a functioning common operating picture for disasters. That talks about climate resilience while cutting the funding for it. That maps hazards for ratepayers but not for tourists.

The Herald’s editorial asks the right question: “Those in power must ask: are they doing everything they can to prepare and prevent for such tragedies?” The answer, clearly, is no.

So what would doing everything look like?

It would mean taking geology seriously. Funding councils properly to hire and retain in-house geotechnical expertise instead of relying on expensive, disconnected consultants. Mapping hazards comprehensively, including in areas like campgrounds that don’t generate rates revenue.

It would mean building that “common operating picture” so that when multiple people call 111 between 5am and 8am reporting an active landslide, someone with authority actually gets the information and can order an evacuation.

It would mean treating climate adaptation as the existential priority it is, not as something to be handled through “normal Budget processes” while the money quietly disappears. It would mean a national framework for managing climate risk, backed by serious funding, rather than leaving 67 councils to figure it out on their own with inadequate resources.

It would mean asking hard questions not just about who drove past the slip at 7:45am, but about the decades of policy decisions that left that person without clear protocols, without backup, without the institutional capacity to recognise the risk they were looking at.

And it would mean being honest about what we’re facing. Not “unprecedented” events that no one could have foreseen. But entirely predictable consequences of a warming climate colliding with decades of underinvestment, deregulation, and wishful thinking.

Some will continue to say it’s “too soon” to talk about all this. That we should wait for the inquiry, respect the families’ grief, not “politicise” the tragedy.

But the politics were already there, in every decision that led to this point. The question isn’t whether we talk about them. It’s whether we’re honest about what they reveal.

Six people are dead. Without big reform – real reform, not just procedural tinkering – authorities will continue to fail New Zealanders. The Mount Maunganui tragedy is simply the most visible, most heartbreaking sign of a system that isn’t working.

The only question now is whether we have the political will to fix it.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Director of the Democracy Project

Further Reading: