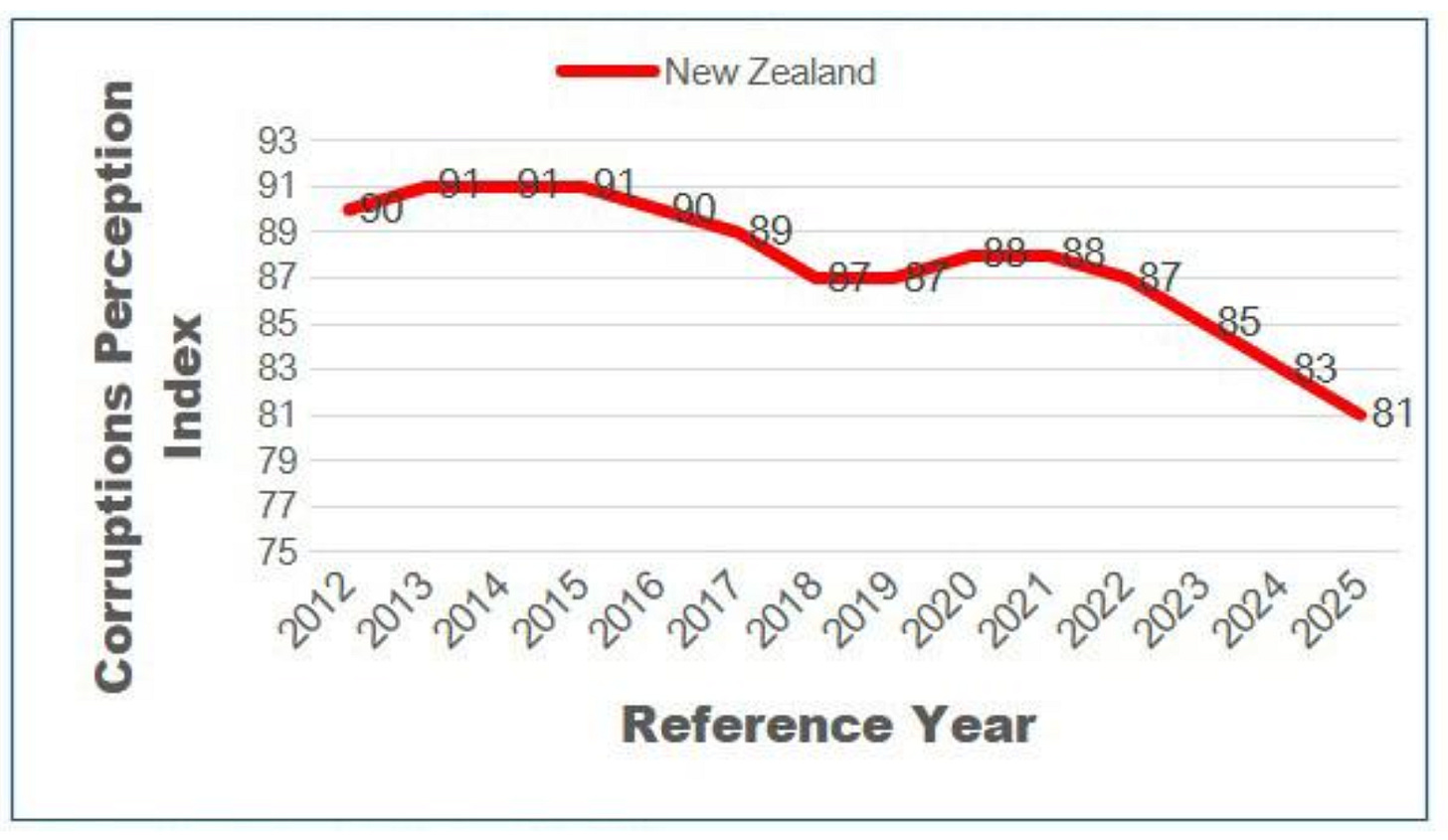

New Zealand’s slide down the global corruption rankings has become so predictable it barely causes a stir. Tonight, Transparency International released its annual Corruption Perceptions Index, and New Zealand has dropped again: from 83 to 81, losing another two points and sinking to equal fourth alongside Norway. We are now eight points behind Denmark, which continues to sit comfortably at the top. Over the past four years, New Zealand has lost ten percent of its total score. That’s not a blip. It’s a pattern.

The question isn’t whether we should be worried. It’s why we aren’t more worried.

The Numbers behind the numbers

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is a composite index, built from 13 international surveys and assessments. Eight of them cover New Zealand. Each year, Transparency International runs a peer-reviewed process to weight the contributing sources and maintain comparability over time. So while some like to dismiss it as “just perceptions,” the methodology is more rigorous than critics suggest.

This year, New Zealand’s decline was driven primarily by two of the eight contributing surveys: the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook and the World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey. Both capture the views of senior business executives. These are people who actually deal with government processes, contracting, and regulation. In the IMD survey, respondents were asked a blunt question: “Does bribery and corruption exist, or not?” In the WEF survey, executives were asked how common it is for firms to make undocumented payments or bribes connected with imports, exports, public utilities, tax, public contracts, and judicial decisions. They were also asked about diversion of public funds.

The responses, to put it simply, were worse than last year. Senior New Zealand business leaders are telling the world they have growing concerns about misconduct in the public sector, particularly where it interfaces with the private sector.

Now, some will read this and shrug. “We’re still fourth in the world,” they’ll say. “What’s the problem?” The problem is the direction. Denmark is stable at 89. Finland is at 88. Singapore (which now blocks NZ from reclaiming the top spot in Asia-Pacific) is at 84. Countries like Switzerland, Sweden, and the Netherlands have also slipped, but none have declined as steeply or as consistently as New Zealand. We used to share the podium with Denmark. Today, we are eight points behind. That gap would have been unthinkable a decade ago.

What the taskforce found

The timing of this year’s CPI release could hardly be more awkward. Today also saw the publication of the Anti-Corruption Taskforce’s pilot report, which is the first attempt by New Zealand law enforcement to get a system-wide picture of fraud and corruption inside the public sector.

The taskforce was led by the Serious Fraud Office, with support from New Zealand Police and the Public Service Commission. Six government agencies participated: Inland Revenue, ACC, Corrections, MSD, Land Information New Zealand, and Sport New Zealand. Over a 15-month period, those agencies reported 446 alleged incidents of internal fraud and corruption. Many were classified as misconduct. But they also included cases that warranted criminal investigation.

Here’s the key sentence (and it’s damning): “Cases of internal fraud and corruption are almost certainly being under-reported, due to a number of factors, and the true scale of the issue remains unclear”.

The taskforce found wild variation between agencies. One agency reported having no or only partial controls for 70% of the assessment criteria. Another reported the same for 64%. These aren’t obscure technical benchmarks. They include basics like centralised monitoring of gifts and benefits, due diligence checks on suppliers, and fraud risk assessments.

Agencies weren’t even clear on when they should refer suspected corruption to the police or the SFO. In one case, an agency was told a staff member had been offered a five-figure bribe. The bribe wasn’t accepted. But the internal report was so sparse that a referral to law enforcement was essentially impossible. The taskforce pointedly noted that offering a bribe is itself a criminal offence, whether or not it’s accepted. Some agencies apparently didn’t understand that.

The report cited a UK study estimating that between 0.45 and 5.6% of New Zealand’s public sector spending is lost to fraud, corruption, and error each year. Applied to Budget 2025, that comes to somewhere between $823 million and $10.24 billion. It’s a huge range. But even the lower end should concentrate minds.

Perhaps the most revealing finding was about how government agencies treated internal corruption. Many cases were handled as employment matters. When staff resigned mid-investigation, the matter would often just evaporate. In one case the SFO highlighted, a woman used forged references to get a public sector job, was caught, resigned, and then successfully applied for another public sector role using the same fake references. She and her husband went on to fraudulently obtain $2 million.

The taskforce report is careful and measured. Read it closely, and you see a public sector that’s all talk on integrity but short on action.

Nippert puts his finger on the problem

Herald journalist Matt Nippert is one of the very few reporters in New Zealand who consistently digs into white-collar crime, and he called today “a red-letter day for white-collar-crime watchers”. He’s right. The simultaneous release of the CPI and the taskforce report amounts to a one-two punch that should end the complacency once and for all.

Nippert made a point that deserves wider attention. He noted that for too long, “New Zealand exceptionalism has seen the country ignorant and inert in defending against the pernicious risk – and reality – of corruption and other crimes against public trust”.

He also raised the OECD’s repeated assessments of New Zealand’s compliance with the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials. During several recent review trips, the OECD noted that New Zealand’s lack of foreign bribery prosecutions was, according to Nippert, “not salutary, but concerning”. In other words, the absence of cases isn’t evidence that things are clean – it’s evidence that we’re not looking hard enough. Or that we don’t have the tools and resources to do so.

This is a crucial insight. Our previous chart-topping CPI status was, as Nippert put it, perhaps more due to “ignorance than saintliness”. As Nippert put it, when corruption isn’t being noticed, let alone investigated or prosecuted, “absence of evidence can be mistaken for the reverse.” It’s the old problem: if you don’t look under rocks, you don’t find bugs.

What about TINZ?

Transparency International New Zealand issued a strong press release today. Chair Anne Tolley said the country’s declining score “signals growing risks to New Zealand’s democratic integrity and global reputation”. She called for a national anti-corruption strategy, lobbying regulation, timely disclosure of political donations, and enhanced oversight of electoral processes.

All good. But I have to say – and regular readers of this newsletter will know this is a recurring theme – I remain sceptical about the local chapter’s track record on this issue.

For years, TINZ used the CPI as essentially a cheerleading exercise for New Zealand. When we topped the rankings, the press releases celebrated. When politicians pointed to our number one status as proof that reform was unnecessary, TINZ didn’t push back hard enough. Its reports tended to be cautious, abstract, and careful not to offend the Wellington establishment. No names were named. No scandals were cited. The effect was to downplay the problems and make for rather dull reads that, unsurprisingly, got ignored.

This cheerleading has contributed to the very complacency that allowed our score to erode. The basic orientation in the Wellington beltway towards corruption has been to celebrate New Zealand’s low-corruption status, and then use it to justify why we don’t need to implement the integrity reforms that comparable countries have. No lobbying register? We’re number one on the CPI, so clearly we don’t need one. No beneficial ownership register? Surely a country this clean doesn’t require the compliance burden.

To be fair, TINZ has shifted its tone since about 2024. The appointment of Julie Haggie as CEO brought a more forthright approach, and the organisation has begun to call things out more directly. Their analysis of this year’s CPI is more detailed and more honest than in previous years. The “Level the Playing Field” campaign, launched with the Helen Clark Foundation and Health Coalition Aotearoa, is a genuine step forward on lobbying reform.

But TINZ still has structural problems. It is chaired by a former National Party Cabinet Minister. It receives funding from government agencies, including the intelligence services. Anti-corruption campaigner Tex Edwards (no relation) has publicly accused TINZ of “essentially falling asleep at the wheel” while lobbyist control of government policy ran rampant. His view, which I think has merit, is that TINZ has been “more of an obstacle for the integrity agenda than a solution,” partly because of its proximity to the establishment it should be scrutinising.

Is it possible to be both an insider and a watchdog? Sometimes. But it requires a level of independence and willingness to cause discomfort that TINZ has not always demonstrated.

The Bigger picture

Step back, though, and it’s even bleaker. New Zealand remains the only Five Eyes country without a whole-of-government national anti-corruption strategy. We have no lobbying register – the OECD ranks us 34th out of 38 countries for regulating influence on policymaking. We have no cooling-off period for ministers entering lobbying. We have no beneficial ownership register, despite repeated promises and FATF criticism. We have no independent anti-corruption commission.

Australia, by contrast, established a National Anti-Corruption Commission and has seen its CPI trajectory turn upward. So while NZ talked about some reforms, Australia actually acted.

And here at home? In 2025, corruption convictions and fraud cases worth tens of millions of dollars ran through the courts: in construction, building inspection, infrastructure, health, procurement, and IT. There were charges involving police officers, corrections staff, and border officials. New Zealand recorded its first criminal cartel convictions, involving bid-rigging in construction, and the Commerce Commission brought civil cartel proceedings against courier companies for price-fixing and customer allocation. Kiwis lost $265 million to fraudsters in 2024/25.

The SFO now estimates that around 40% of its current caseload involves allegations of corruption. That is a remarkable number for a country that supposedly doesn’t have a corruption problem.

Meanwhile, the CPI itself doesn’t even capture some of the things that matter most in a country like New Zealand. It doesn’t measure lobbying influence, the revolving door between politics and business, political donation influence on policy, or regulatory capture. It doesn’t capture private sector corruption, money laundering, or organised crime.

As I’ve argued before, the CPI was designed to measure old-fashioned bribery (brown envelopes and embezzlement). It was never built to detect the sophisticated legal corruption that characterises wealthy democracies. A country can score 81 on the CPI and still have a political system severely captured by vested interests.

Where to from here?

The Government’s taskforce report ends with a line about “recognising the value in protecting a strong reputation rather than trying to buy back a ruined one”. Fair enough. Except it shows a mindset still primarily about brand management rather than democratic accountability. The goal shouldn’t be protecting New Zealand’s “reputation.” The goal should be making sure our public institutions actually work for ordinary people, not for insiders and vested interests.

Finding fraud, as the taskforce report itself notes, “is a good thing”. It means the system is working. We need to get past the idea that detecting corruption is embarrassing. What should be embarrassing is choosing not to look for it.

The global picture is grim too. Transparency International’s global report noted the CPI average has dropped for the first time in more than a decade, to just 42 out of 100. Only five countries now score above 80, which is down from 12 a decade ago. The number of countries scoring below 50 now stands at 122 out of 182. There is a pattern of democracies weakening, from the United States (64) to France (66) to the United Kingdom (70).

New Zealand is part of that wave. And the longer we pretend we’re immune to it, the further we’ll fall.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Director of the Democracy Project

Further Reading: