Democracy Deep Dive: Corporate lobbyists’ quiet victory in the retirement villages battle

The Government’s announcement this week on reforming the Retirement Villages Act has been dressed up as a victory for fairness and consumer protection. Ministers have visited retirement villages for the cameras, promising “clarity” and “straight-up information” for older New Zealanders handing over their life savings. Who could object to that?

But strip away the press release language, and you find something less inspiring. The retirement village industry has largely protected its profitable status quo. The grassroots residents who campaigned for years for genuine reform have been handed a few crumbs. And the whole episode stands as a case study in how corporate power operates in New Zealand, using sophisticated lobbying techniques that most citizens never see.

Let’s be clear about what happened here. The Retirement Village Residents Association, a genuine grassroots organisation representing tens of thousands of New Zealanders living in these villages, wanted a mandatory buyback period of 28 days. That is, when a resident leaves or dies, the operator would have to return their capital within a month. This would force operators to treat repayment as a genuine obligation rather than something they can delay indefinitely while continuing to profit.

What did the Government announce? Twelve months. Not 28 days. Not the six months that some compromise advocates suggested. A full year.

For a grieving family waiting to settle an estate, or an elderly person who needs their capital to fund a move to hospital-level care, twelve months is an eternity. It means the industry gets to continue holding onto people’s money, essentially interest-free for half that time, while families remain in financial limbo. Several major operators have already indicated the changes won’t affect them much, because they were broadly doing this anyway. Ryman Healthcare bluntly told journalists they don’t expect to be impacted.

Even worse is the decision to make these changes non-retrospective. The new protections will only apply to contracts signed after the law comes into force. The 56,000 New Zealanders currently living in retirement villages, the people who led the fight for reform, will be stuck with their existing contracts. As the genuine Retirement Village Residents Association president Brian Peat put it, this creates a “two-tier system” where existing residents are left in limbo.

Think about the perversity of that. These are often people in their 70s, 80s, and 90s. They mobilised. They submitted. They marched on Parliament. They told their stories to the media. And now they’re being told the changes they fought for will benefit the next generation, not them. Many won’t live to see the benefits flow. Consumer NZ’s Kate Harvey captured the feeling: “We’re gutted for current residents who have been campaigning so hard for some fairness.”

The Lobbying machine

How did the industry achieve this outcome? Through the time-honoured methods of corporate influence in New Zealand, which remain largely invisible to the public.

This is a multi-billion dollar sector. The “Big Six” operators, including Ryman, Summerset, Metlifecare, and Oceania, have assets measured in billions. With that kind of money at stake, they can afford the best lobbying talent and deploy sophisticated strategies that ordinary citizens simply cannot match.

The Retirement Villages Association, the industry lobby group, brought in Capital Government Relations, the lobbying firm owned by Labour’s Neale Jones and National’s Ben Thomas. This is bipartisan influence-peddling at its finest, ensuring access to power regardless of who’s in government. Senior lobbyist Mike Jaspers, who previously worked as a spin-doctor for Prime Ministers Jacinda Ardern and Helen Clark, was deployed to help with the media campaign.

Throughout the review process, operators warned that strict regulation would have a “chilling effect” on new developments. They threatened that if forced to return residents’ money within a reasonable timeframe, they would stop building new units, worsening the housing shortage for seniors. This is the classic nuclear option of industry lobbying: regulate us and everyone will suffer. The Government appears to have swallowed this argument wholesale, even though the industry has been extraordinarily profitable for years.

The Astroturf operation

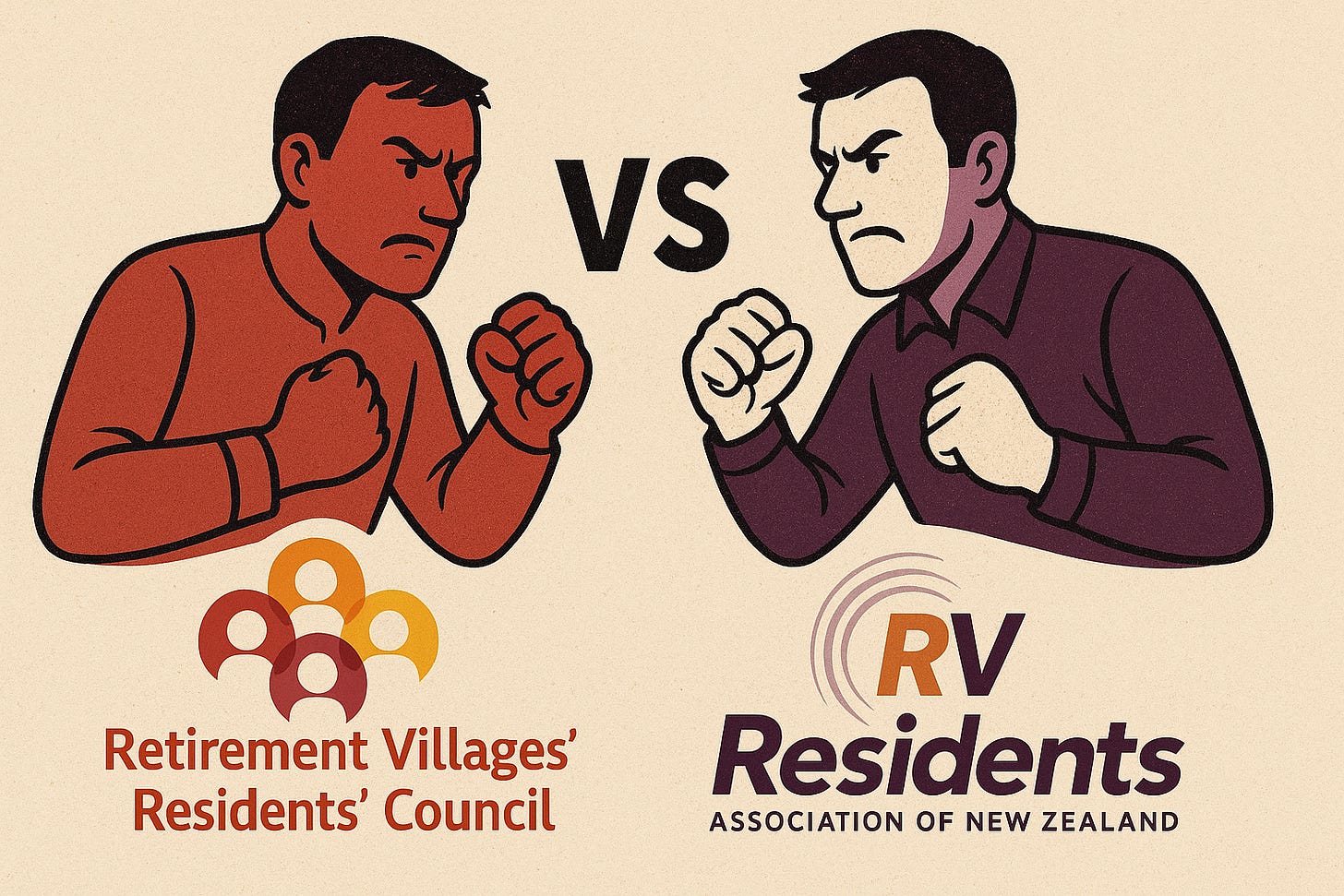

But perhaps the most cynical tactic was one I wrote about in May, in a column called “A Case study in the dark arts of lobbying”. Faced with a determined grassroots residents’ association calling for strong reforms, the industry simply created its own rival organisation.

The Retirement Village Residents Council was established in late 2023, funded entirely by the operators through their lobby group, with Capital Government Relations handling the media work. Notice the name: Retirement Village Residents Council versus Retirement Village Residents Association. Just one word different. Designed to confuse. Designed to muddy the waters.

This is textbook astroturfing, creating the appearance of grassroots support that is actually manufactured by corporate interests. The council’s members aren’t elected by residents. Ordinary village residents can’t even join. One council member, Denise Whitehead, has a 32-year career in retirement village development and previously sat on the Retirement Villages Association’s executive committee. A former industry executive is now positioned as someone representing residents against the operators.

The strategy worked beautifully. Government officials quickly began consulting with both groups, treating the industry-funded council as equivalent to the genuine residents’ association. When politicians wanted to appear “balanced,” they could point to this manufactured moderate voice. When they wanted to avoid the more radical demands of actual residents, they had cover.

We can see this playing out in the response to this week’s announcement. The genuine Retirement Village Residents Association expressed deep disappointment. Brian Peat pointed out that the 12-month deadline “falls far short” of what residents need, noting that their members overwhelmingly considered three months fair and reasonable. He warned of the divisive two-tier system for existing residents.

But the industry-funded council? Their spokesperson Carol Shepherd called the changes “a welcome step in the right direction” that “strike a better balance, being fairer for residents and village operators alike.” Note that language: “fairer for operators.” It’s an unusual thing for a genuine consumer advocacy group to worry about fairness to the corporations they’re meant to be challenging.

The Media falls for it

The success of this astroturf operation is evident in today’s media coverage. The Otago Daily Times ran an editorial headlined “Retirement village changes a good start.” It quoted the industry-funded council alongside the genuine residents’ association, treating them as equivalent voices. No mention that one is funded by the very operators being regulated. No suggestion that there might be a conflict of interest.

This is exactly what the lobbyists paid for. By having a “residents’ voice” that praises the Government’s watered-down reforms, the industry de-legitimises the anger of actual residents. It allows ministers to say they’ve listened to stakeholders and struck a balance. It neutralises the political heat that might otherwise force more meaningful change.

The review process became something of a tri-partite arrangement: the industry lobby group, the astroturf residents group, and the real residents’ association. Two out of three voices at the table were effectively funded by operators. The fix was in from the start.

What’s really at stake

It’s worth understanding why the industry fought so hard to preserve its model. The retirement village business is extraordinarily profitable precisely because it’s tilted heavily in favour of operators.

Residents don’t own their units. They pay large sums, often half a million dollars or more, for a “licence to occupy.” When they leave or die, operators take a deferred management fee of 20 to 30 percent. Any capital gains go entirely to the operator. While waiting for a unit to be resold, families have been forced to keep paying weekly fees, bleeding estates for months or years in some cases.

One resident, Pat Price, handed over $695,000 for her Auckland unit in 2020, only to leave last year for family reasons. Months later, she was still waiting for her $515,000 repayment. The village cited a sluggish housing market. Stories like hers are common.

This system generates huge cash flows for operators. They can take their time reselling, benefit from rising property values, and keep collecting fees from departed residents. It’s a business model that thrives on ambiguity and imbalance. A genuine review might have disrupted this. Instead, it’s been protected.

A broader lesson

The retirement villages saga offers a textbook case in how power really works in New Zealand. We have institutions that look democratic: parliamentary reviews, public consultations, select committee processes. We have ministers who talk about listening to all voices and striking balance.

But underneath this veneer of process, corporate interests deploy resources that grassroots citizens simply cannot match. They hire professional lobbyists with connections across the political spectrum. They create astroturf organisations. They feed carefully crafted messages into media coverage. And it works.

Labour’s seniors spokesperson Ingrid Leary has a member’s bill proposing a three-month repayment period, which she argues “no one should be waiting a year to get their own money back.” She’s right, but her voice is drowned out in the post-announcement consensus-building.

Retirement Commissioner Jane Wrightson welcomed the reforms as a “landmark moment.” She praised the balanced approach. But for residents and their families, this is a defeat dressed up as progress. They wanted real protection. They got cosmetic change that largely codifies what the better operators were doing anyway.

The genuine Retirement Village Residents Association can hold their heads high. They fought for fairness against formidable odds. But they were up against more than just inertia. They were up against a well-oiled influence machine, complete with lobbyists who know how to navigate Wellington and an astroturf operation designed to manufacture moderate consent.

The industry has successfully protected its patch. The Bill won’t even hit Parliament until mid-2026, giving plenty of time for further watering down during the select committee process. Consumer NZ’s Jon Duffy warned that cabinet decisions have been diluted before: “We need to be really conscious of death by a thousand cuts.”

For observers of New Zealand’s democracy, this is a dispiriting reminder of how things actually work. When a relatively powerless group, elderly residents of modest means, goes up against wealthy corporations backed by professional lobbyists, the outcome is rarely in doubt. The operators deployed everything from high-level lobbying to a manufactured residents’ group to make sure their voice was loudest in the room.

The seniors who helped build this country deserve better than a system where their genuine voice is drowned out by faux “representatives” financed by the companies they’re trying to reform. The astroturf Retirement Village Residents Council is still out there, still being quoted, still muddying the waters. Capital Government Relations have earned their fees. The fight for integrity in our democracy continues, inside retirement villages and far beyond.

So, the fight for fairness in retirement villages is not over. The genuine residents will continue to campaign, but they now know exactly what they are up against: a machinery of influence designed to ensure that in the battle between people and profits, the house always wins.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Director of the Democracy Project

Our appreciation again Bryce for the analysis. We certainly need to attend to changing the lobbying laws, plus the rest!

So disgusting- but I've seen it in some many policy areas- overseas pensions is another- people lose heart when they are told to make do with crumbs and it is too hard to keep fighting