Integrity Briefing: Parliamentary inquiry puts more than just one MP on trial

What began as a low-key “Beltway story” of marginal interest has escalated into a significant test of New Zealand’s parliamentary integrity. The announcement that Parliament’s Registrar of Pecuniary Interests, Sir Maarten Wevers, will launch a formal inquiry into National MP Carl Bates’ failure to declare 25 properties marks a pivotal moment. Just last week, this was a story the government might have hoped would fade away. Today, it has become an official matter of accountability that cannot be ignored.

Sir Maarten’s decision to initiate a full inquiry is anything but routine. In a letter from his office, he made it clear that a preliminary review assessed whether the matter was merely “technical or trivial.” By determining that a full inquiry is “warranted,” the Registrar delivered a formal judgment: this issue is substantial, and there may well be a breach of disclosure obligations that demands investigation. This validation by a respected, non-partisan officer of Parliament lifts the controversy out of the realm of partisan point-scoring and places it squarely within the formal machinery of accountability.

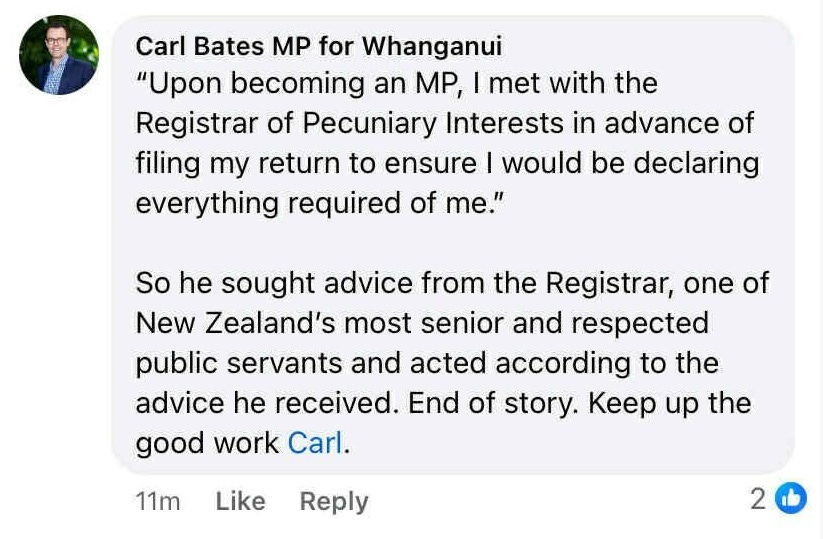

The seriousness of this development stands in almost comical contrast to early attempts to wish the story away. After the revelations first broke, a supportive comment promptly appeared on Facebook: “he sought advice from the Registrar… and acted according to the advice he received. End of story. Keep up the good work Carl.”

The only problem was that the post came from Bates’ own official MP account. Bates attributed the gaffe to a staffer’s “silly mistake,” but the phrase “end of story” proved deeply ironic. The story was clearly not over at all. In fact, the ham-fisted social media defence only fanned the flames — political reporters had a field day with the apparent sock-puppet self-endorsement, and public suspicion grew rather than subsided.

If everything had truly been above board, why was an MP (or his team) anonymously defending his hidden assets online? The optics of an MP seemingly applauding himself underscored the public’s concern that this was not a trivial paperwork mix-up, but a serious breach of transparency and trust. With the launch of a formal inquiry, the Carl Bates saga is just beginning in earnest.

Why the Register matters: A Tool against corruption, not a tick-box exercise

The Register of Pecuniary Interests is not some dry bureaucratic formality. It is a fundamental pillar of democratic accountability, designed to give the public confidence that politicians are legislating in the national interest – not their own financial interest. Its entire purpose is to expose potential conflicts of interest before they can corrode public trust.

A few years ago, I interviewed Sir Maarten Wevers about his role overseeing the Register. He explained that the Register was created “so that the public know what the interests of those members are. So that when decisions are made by the House they know whether or not there might be a conflict of interest and that people might be making decisions that favour entities with which they’re associated and it’s been a great innovation for transparency [in the] political process”.

His words cut to the heart of the Bates case. This is not an abstract or technical issue. Trusts linked to Bates and his family own 25 properties, many of them rentals in his Whanganui electorate – making them among the region’s biggest private landlords. As an MP, Bates votes on legislation that directly impacts the property market and landlords, including the current government’s restoration of interest deductibility for rental properties — a policy worth an estimated $2.9 billion to landlords. The public has an absolute right to know the full extent of an MP’s property holdings when their elected officials are making decisions of this magnitude, especially during a national housing crisis. The Register of Interests is the mechanism meant to provide that crucial transparency. When it fails, the public is left to wonder who their representatives are truly serving.

The Anatomy of a loophole and a history of inaction

Carl Bates’ defence is that he followed the rules and even sought the Registrar’s advice on what to declare. And that is precisely the problem. His case exploits a systemic loophole in Parliament’s disclosure rules — a loophole that Parliament was explicitly warned about after the Michael Wood affair, yet chose not to close. This elevates the issue from one MP’s personal oversight to a case of deliberate institutional inertia.

As I detailed in a previous column (“The loophole allowing MPs to hide their property empires”), the mechanism Bates used is a masterclass in legal obfuscation. After winning the election, Bates transferred his shareholdings in two property-owning companies to a new entity called Seize the Day Trustee Company Limited. That trustee company is held by the Carpe Diem Trust, of which Bates happens to be a beneficiary. This two-step shuffle creates a legal firewall, allowing him to claim he has no direct interest in the 25 properties themselves – technically true on paper, but deeply misleading in spirit.

This loophole was not some unforeseeable quirk; it was a disaster waiting to happen. In 2023, the inquiry into Labour Minister Michael Wood’s undeclared airport shares highlighted this exact ambiguity in the rules. In its final report, Parliament’s Privileges Committee noted that both it and the Registrar agreed that more clarity was needed on how interests held in trusts should be declared. The committee formally recommended that the Standing Orders Committee (which writes Parliament’s rules) should clarify the requirements. Yet since that official recommendation was made, absolutely nothing has changed. Parliament was put on notice about this precise weakness in its transparency regime and failed to act. That inaction set the stage for exactly what we have now: the non-disclosure of a multi-million-dollar property portfolio by an MP, perfectly legal under muddled rules that everyone knew were flawed.

In fact, warnings about these kinds of loopholes go back even further. All the way back in 2008, then-Foreign Minister Winston Peters infamously failed to declare a $100,000 donation that had been routed through a lawyer’s trust account. In response, the Privileges Committee censured Peters for breaching the disclosure rules and stressed that “all distinct interests must be declared, regardless of whether they are channelled through a trust or third party.” The lesson was clear even then: an MP shouldn’t be able to hide an interest just by parking it in a trust. Yet neither that precedent nor the more recent Wood scandal was enough to spur a rule change.

Tellingly, when I asked Sir Maarten Wevers about the role of trusts in disclosures during our interview, he noted that an MP must declare their interest in a trust, and that this can then be “pursued by the media or other people.” It was a polite way of acknowledging the system’s weakness: it effectively relies on journalists and outsiders to do the forensic digging that the Register itself should have made unnecessary. In other words, the loopholes are an open secret, and the system has been coasting on the assumption that someone else will connect the dots.

The Wevers inquiry: Precedent and expectation

Given Sir Maarten Wevers’s distinguished career as one of New Zealand’s top public servants – including his handling of the Michael Wood inquiry – we can expect a rigorous and impartial investigation from him. His past findings show a deep concern for how these failures damage public trust not just in an individual politician, but in the integrity of the entire political system. In his 2023 report on Michael Wood, Sir Maarten wrote that Wood’s incorrect returns had “cast a shadow over the entire Register, and the trust and confidence that the public are entitled to expect they can have in their elected representatives.” He also criticised Wood’s “worrying and ongoing lack of awareness of the need to correct errors” in his disclosures.

The Bates case is arguably far more significant than Wood’s, given the sheer scale of the assets involved — 25 properties worth an estimated $10 million, versus around $12,000 in shares in Wood’s case — and because it strikes at the heart of the housing crisis. If Sir Maarten was gravely concerned about the damage caused by the Wood affair, his conclusions on Bates are likely to be just as severe, if not more so. The inquiry will see him gather evidence and report his findings to the House. If he determines that a question of privilege is involved, the matter will automatically be referred to Parliament’s ultimate disciplinary body, the Privileges Committee.

However, this inquiry puts Sir Maarten in a uniquely challenging position. He is investigating a case where the MP’s central defence is “I followed the advice I was given” – advice that originated from the Registrar’s own office, based on the very rules that are now glaringly shown to be flawed. Therefore, his final report cannot simply focus on Bates’ personal conduct or compliance. To be credible, it must also address the systemic failure of the rules he is tasked with administering. This dynamic makes the inquiry’s outcome potentially far more consequential than a one-off reprimand. It could finally force the Standing Orders Committee (and Parliament itself) to confront the loopholes that it has so far been content to ignore.

A Systemic rot that demands sunlight

The Carl Bates affair is a symptom of a much larger disease in our politics: a culture of legalistic evasion that has been allowed to fester in Parliament. It’s a culture of following the letter of the law while brazenly betraying the spirit of transparency.

As RNZ’s Mediawatch pointed out in its coverage of this issue on Sunday, housing stories in the media are often framed as matters of property investment and personal gain, rather than as questions of social policy or political accountability. Major outlets run far more stories treating houses as “investments” than they do examining solutions for housing affordability or homelessness. This media context makes the Bates investigation even more significant. It has the potential to refocus the conversation from “How can investors maximize returns?” to “Are our leaders serving the public or themselves?”

In fact, Mediawatch highlighted and quoted my analysis about exactly this problem. I argued that an MP with a dozen rental properties might think twice about openly voting to end tax write-offs for landlords. But if those properties are quietly stashed in a trust, the conflict stays off the front page.

And that is the crux of it: these convoluted trust arrangements allow politicians to have massive skin in the game on issues like housing, while keeping those interests out of the public eye. It’s a recipe for policy bias and public cynicism. How can we honestly expect Parliament to tackle the housing crisis boldly and impartially when so many MPs are secretly profiting from the very status quo that has created the crisis – skyrocketing property values, housing shortages, and tax-free capital gains?

Indeed, the Bates saga shines a light on a broader reality: New Zealand’s Parliament is stacked with property owners and trust beneficiaries. This isn’t one rogue MP exploiting a grey area — using trusts to manage assets is common practice in our legislature. Roughly a third of all MPs declare property holdings in trusts, and many others simply own multiple properties outright.

Even some politicians themselves have acknowledged the inherent conflict of interest. Back in 2017, Act leader David Seymour – who at that time didn’t own a house – pointed out that “the average National MP owns 2.2 properties of their own.” He suggested this was one reason the government tended to offer only half-hearted housing solutions “that you’d almost suspect weren’t supposed to work – because they certainly haven’t.”

Likewise, former Green Party co-leader James Shaw quipped that the prevalence of multi-property owners in Parliament is “a good signal for why there isn’t a capital gains tax in this country.” In short, the personal financial interests of MPs as landlords and property investors create a systemic bias. There’s a built-in disincentive for them to pass laws that might lower property values or introduce tough tax measures on housing – and, it appears, a disincentive to tighten transparency rules that would expose just how deep this vested interest runs.

This official inquiry into Bates provides a crucial opportunity to lance the boil that is this wider culture of evasion. But ultimately, the long-term solution does not lie with the Registrar or any one watchdog. It lies with the MPs themselves, particularly those who write the rules on the Standing Orders Committee. They are, in effect, judge and jury over their own disclosure requirements.

And as I cautioned when this story first broke, real change will not happen without strong pressure from outside Parliament. “There really has to be extra strong pressure put on the institution of Parliament to clear this up,” I told the New Zealand Herald, “because it’s just going to reduce public trust in the political process more and more – and rightly so.”

Time to close the loopholes

The Carl Bates affair should be a watershed moment for New Zealand. It’s proof-positive that the current disclosure rules are not fit for purpose. Tinkering around the edges won’t cut it – we need urgent, substantive reform to restore trust in our system. Two key fixes stand out:

Mandate true transparency for trusts: The rules must explicitly require MPs to declare significant underlying assets they benefit from, even if those assets are held via discretionary trusts or shell companies. No more hiding behind legal technicalities—if an MP stands to gain financially from a property or investment, it needs to be on the public record. This includes closing the specific “Bates loophole” by making it crystal clear that an MP can’t dodge disclosure by shuffling assets into a company owned by a trust. The intent of the Register must be honoured: disclose what you really own or benefit from, not just what you directly hold on paper.

Strengthen and clarify the rules: Parliament should finally implement the Privileges Committee’s 2023 recommendation and eliminate the ambiguity surrounding interests held in trusts. The Standing Orders (Parliament’s own rulebook) need to be tightened and modernised. The default should be simple: when in doubt, disclose. If there are grey areas clever lawyers can exploit, those must be rewritten in plain language to cover modern trust and company arrangements. No more loopholes that undermine transparency.

Fortunately, an opportunity for meaningful change is at hand. The impending 2026 Review of Standing Orders – normally a dry, procedural exercise – could be the vehicle to enshrine these reforms. Public submissions for that review are currently being gathered – they close at midnight – and this time around the stakes are high. It will show whether our Parliament is serious about cleaning up its act, or content to keep the status quo and watch public trust continue to erode. The ball is in the MPs’ court to prove that they deserve the public’s confidence.

At the end of the day, this debacle is not really about one MP’s slip-up on a form. It is about the integrity of our democracy. It’s about whether New Zealanders can have confidence that the laws of the land — especially laws addressing a crisis like housing — are being made for the public good, and not to protect the private wealth of a political class hiding assets behind trusts and legal smoke screens. Sunlight is the best disinfectant, and it’s time for Parliament to let it in.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Director of The Integrity Institute

Note to media: I am available for further comment and interviews on the parliamentary inquiry, the Register of Pecuniary Interests, and the need for reform of political transparency rules.

Further reading:

Bryce Edwards: Integrity Briefing: The Loophole allowing MPs to hide their property empires

Chris Knox & Jaime Lyth (Herald): Parliament launches inquiry into National MP Carl Bates’ undeclared 25 properties

No Right Turn: This corruption has to stop

Russell Palmer (RNZ): Inquiry to look into National’s Carl Bates’ failure to declare properties

Thomas Coughlan (Herald): Whanganui MP Carl Bates deletes FB post praising himself after housing revelations

Chris Knox (Herald): MP put 25 properties in family trust before facing financial declaration rules (paywalled)

Colin Peacock (RNZ): Mediawatch: Property news pumping up the market?

Totally supportive and would like to see any Trust declared by an MP, openly declare what assets etc. Are held within it. Great work.

Thanks Bryce for a succinct commentary on this matter. Very much doubting that it's a coincidence that the loophole and flawed advice is related to property. There is in my view something particularly unhealthy about the widespread obsession with property as a wealth generator, as it is largely parasitic, or perhaps the term paralytic would be more appropriate, with value an outcome of internal churn factors, such as failure to release adequate residentially zoned land, rather than real, exportable value that this country so desparately needs. Such internal churn based value is a huge problem for a trading nation that cannot sustain itself from its internal produce. However the culture is now so deeply embedded that politicians of all stripes are desparate to avoid bursting the bubble for reasons of both political and personal gain. So around and around we go.