Annual Audit of Political Donations

Following The Money in 2025: The Democracy Project Annual Audit of Political Donations in New Zealand

By Dr Bryce Edwards, Director, the Democracy Project

Executive Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the $10.5 million in declared political donations received by New Zealand’s parliamentary parties last year. The findings reveal a political financing system under significant strain. While New Zealand maintains a global reputation for low corruption, the patterns of giving documented in this report point to a troubling disconnect between that perception and the reality of how political influence is sought and wielded.

The central argument of this report is that the proximity between large financial contributions from wealthy vested interests and favourable government outcomes is now too close and too frequent to be coincidental. While usually technically compliant with the law, the patterns of these donations are creating undeniable conflicts of interest, eroding public trust, and threatening the foundational principle of democratic equality.

This report is based on data submitted by all registered parties about their donations in the 2024 calendar year, first published in May 2025 by the Electoral Commission, in line with the Electoral Act. This report is the first of a regular annual series on political donations for the Democracy Project, an advocacy and research organisation set up to foster an improved political process in New Zealand.

Key findings of the 2025 report include:

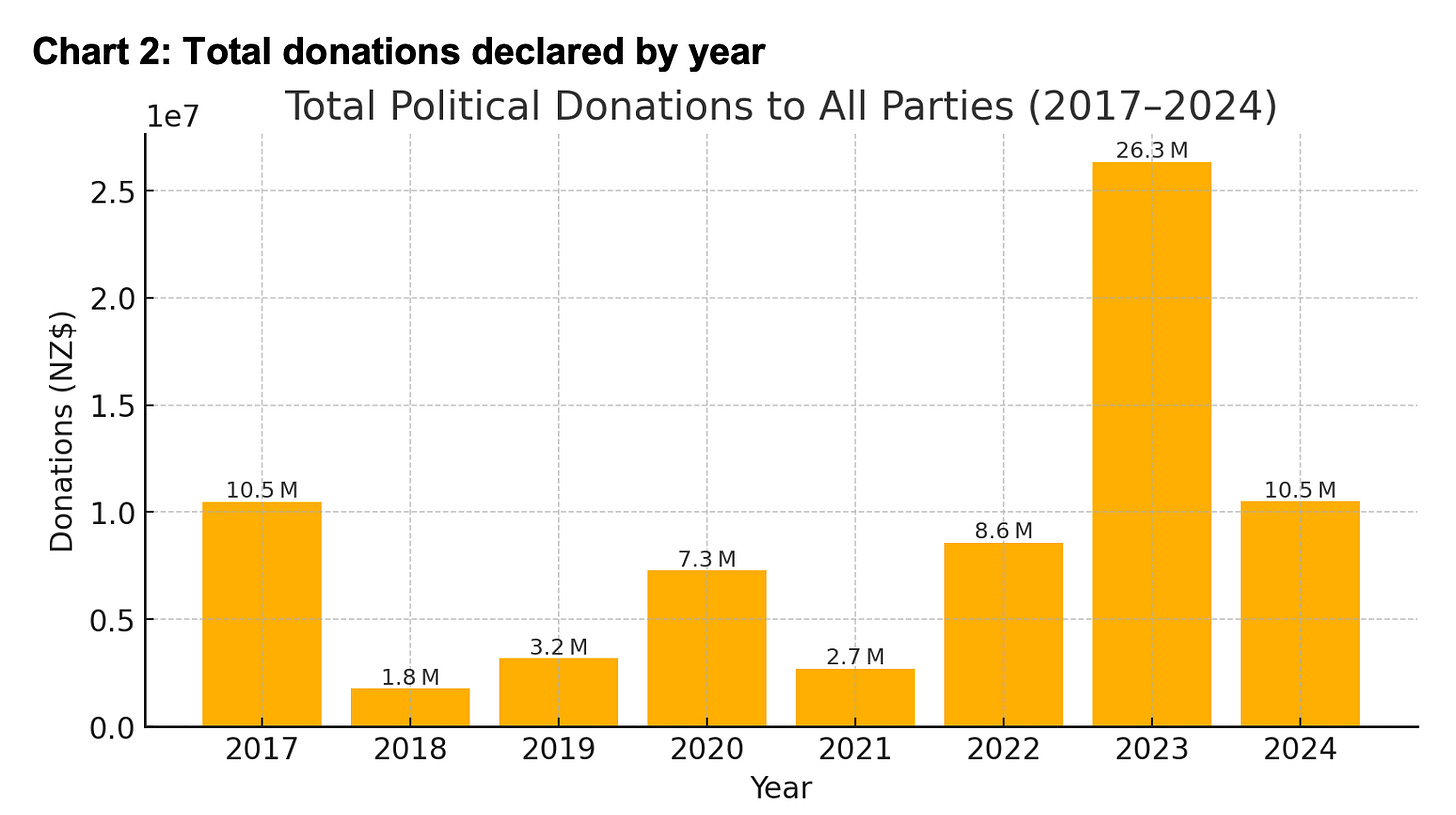

Concentration of Influence: A tiny cohort of donors wields disproportionate financial power. Just eleven donors, all backing the Coalition Government parties, contributed over $1.18 million — more than 10% of all declared funds. Donors giving over $5,000 represented just 0.2% of total donors but accounted for 34% of all money given.

A Tale of Two Funding Systems: New Zealand politics is now funded by two distinct models. On the one hand, the governing coalition (National, Act, New Zealand First) is overwhelmingly financed by large donations from corporate entities and high-net-worth individuals, particularly from the property, construction, and extractive industries. In contrast, the Opposition (Labour, Greens) is funded by a broader base of smaller individual donations and a transparent system of MP tithing.

Systemic Conflicts of Interest: The report details multiple case studies where large donations were followed by significant, tangible benefits for the donor. These include:

1. The Fast-Track Approvals Act: Companies and individuals linked to projects included in the government’s fast-track consenting regime donated over $180,000 to the National and New Zealand First parties in 2024 (Electoral Commission 2025). In several significant cases, the responsible ministers did not recuse themselves from the decision-making process.

2. The Dynes-KiwiRail Affair: A sequence of events saw a transport company donate $20,000 to New Zealand First, receive an $8 million government loan from a fund overseen by a New Zealand First minister, and have one of its directors appointed to the board of KiwiRail by the party’s leader (Hancock 2025a).

3. Perceptions of “Cash for Honours”: Two prominent businessmen were awarded knighthoods in 2025 following their families and companies making a combined total of over half a million dollars in donations to the governing parties over the preceding two years.

Inadequate Regulatory Framework: Current laws fail to prevent practices that obscure the true source of funds, such as “donation splitting” across multiple entities controlled by a single individual. The official processes for managing conflicts of interest, while sound on paper, are proving insufficient to address the public perception that policy and appointments can be bought.

This analysis concludes that New Zealand is at a critical juncture. The “legality defence” — that no rules were broken — is no longer a sufficient answer to the public’s growing cynicism about money in politics. To restore the balance and safeguard the country’s democratic health, this report proposes options for urgent reform, including donation caps, a ban on corporate donations, mandatory stand-down periods for honours and appointments, and enhanced transparency rules to bring New Zealand in line with international best practice.

Introduction: How money in politics is growing discontent

In May this year US President Donald Trump accepted a gift of a US$400 million dollar luxury jet from the government of Qatar (Bruggeman & Barr 2025). The plane is being used by Trump during his term as president and will then be transferred to his presidential library. Trump and his family have also been innovators in the field of accepting political gifts and donations. In late 2024 they launched cryptocurrency products that would allow potential investors to transfer vast sums of money to the Trump family with no transparency or oversight (NPR 2025; Yaffe-Bellany 2025).

Traditionally politicians who accept compromising gifts would attempt to conceal the transaction from the public, and it was often the cover-ups that destroyed careers. 21st century democracies are changing the norms around money and political influence: leaders in the UK, Canada and Germany have also faced serious ethics scandals in recent years, with little or no legal censure (BBC News 2023; House of Commons Privileges Committee 2023). The norms around political influence are changing across liberal democracies, and New Zealand needs to act quickly to protect what integrity remains in our political system.

In July of 2025 Radio New Zealand reported that Dynes Transport Tapanui, a South Island based trucking company that donated $20,000 to New Zealand First in 2024 had received an $8,000,000 regional infrastructure loan (Hancock 2025a). One of the ministers overseeing the infrastructure fund was New Zealand First MP Shane Jones, who insisted that there was no conflict of interest because the donation went to his political party, not to him (Hancock 2025a).

Both New Zealand First and National received donations from applicants to their fast-track process, in which commercial development projects can be deemed exempt from normal laws around consenting and development. Neither party considers this a conflict of interest (Hancock 2024; Hancock 2025b).

The New Zealand public, however, are increasingly suspicious of the funding arrangements of parties. And there is plenty of further evidence from the last year that should be of concern to those worried that donations to politicians might influence the decisions that are being made about the country.

This report considers the 2024 annual returns for the nation’s parliamentary political parties, examining who donated money, to whom. It examines the role that money plays in modern New Zealand politics, the laws that govern it, the problems this poses for democracy and proposes potential solutions.

Unless otherwise cited, all donation amounts and donor information in this report are drawn from the 2024 annual returns submitted by registered political parties to the Electoral Commission and published on 30 April 2025 (Electoral Commission 2025).

Section 1: A System under strain

New Zealand’s political system is defined by a deep and unsettling paradox. Internationally, it is consistently lauded as a bastion of transparency and integrity, ranking among the world’s least corrupt nations (Transparency International 2025). Domestically, however, a profound and growing cynicism has taken hold. A landmark 2023 New Zealand Electoral Survey found that 45% of New Zealanders agree with the statement, “The New Zealand government is largely run by a few big interests,” with only 27% disagreeing (Krewel & Vowles 2024).

This chasm between our international reputation and our domestic reality — an “Integrity Gap” — is the central challenge facing our democracy. It suggests that while we may be free from the overt bribery that plagues other nations, a more subtle and systemic corrosion of our political process is underway.

This report argues that the primary driver of this corrosion is the role of money in politics. The 2024 political donation returns, examined here in unprecedented detail, provide the evidence for what a significant portion of the public already suspects: that access and influence are available for purchase, and that the outcomes of public policy are becoming increasingly tied to the private interests of a small, wealthy donor class. From fast-tracked consents for property developments to seats on state-owned enterprise boards and even the bestowal of knighthoods, the correlation between large financial contributions and favourable government action has become too stark to ignore.

[This investigation considers the annual returns for the nation’s parliamentary political parties, examining who donated money, and to whom. It examines the role that money plays in modern New Zealand politics, the laws that govern it, the problems this poses for democracy, and proposes potential solutions to safeguard what integrity remains in our political system.]

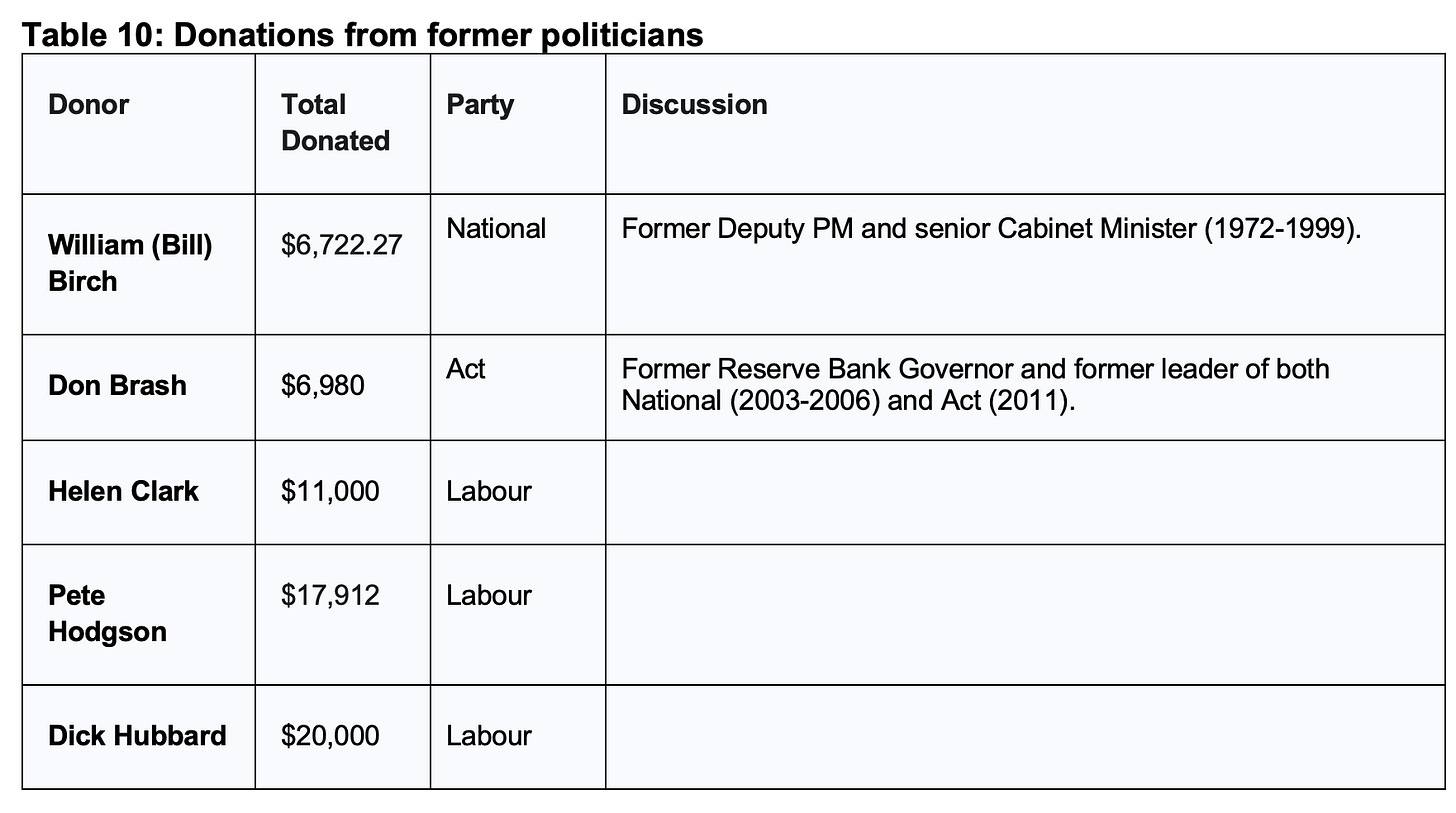

1.1 The 2022 Electoral Amendment Act as a catalyst

The depth of this year’s analysis has been made possible by a crucial, if modest, legislative change. In December 2022, the then-Labour government passed the Electoral Amendment Act, which sought to increase transparency in political financing (Electoral Commission 2022; New Zealand Parliament 2022). The key changes, which took effect from the beginning of 2023, included:

Lowering the threshold for public disclosure of a donor’s identity from any donation over $15,000 to any donation over $5,000.

Requiring parties to report the number and total value of all smaller, non-anonymous donations (between $1,500 and $5,000).

Reducing the threshold for rapid disclosure of large donations in an election year from $30,000 to $20,000.

Parties must commission an auditor’s report if annual donations exceed $50,000 (was $30,000) or if they have any loan over $15,000 outstanding.

Every registered party must file full financial statements (income, expenses, assets, liabilities) plus an auditor’s opinion; the Commission must publish them (Electoral Commission 2022).

This reform was not a panacea, but it has acted as a powerful new lens. By forcing a significant amount of previously “grey” money into the light, the amendment has created a transparency shock. A donation of $14,999 was once invisible to the public; now a donor’s name is required for a contribution less than half that size. The 2024 data, therefore, represents the first full-year picture of political financing under these more revealing conditions, establishing a crucial new baseline for understanding the flow of money in New Zealand politics.

1.2 Thesis statement

The central argument of this report is that the patterns of high-value donations from vested interests in 2024, while usually technically compliant with the law, reveal a system of political financing that is creating dangerous and undeniable conflicts of interest. These patterns are eroding public trust and threaten the foundational principle of democratic equality.

The defence that no specific law was broken is no longer credible when the systemic outcomes so clearly favour a narrow group of financial backers. New Zealand is at a critical juncture and requires urgent, substantive reform — not merely to tweak disclosure rules, but to fundamentally reassert the principle that political decisions must be made in the public interest, free from the distorting influence of private wealth.

Section 2: The New landscape of political finance: Following the $10.5 million

The 2024 annual returns provide a clear statistical snapshot of the financial landscape of New Zealand politics. While a non-election year, the total declared amount indicates a system flush with cash, with funds heavily concentrated among the parties of the governing coalition.

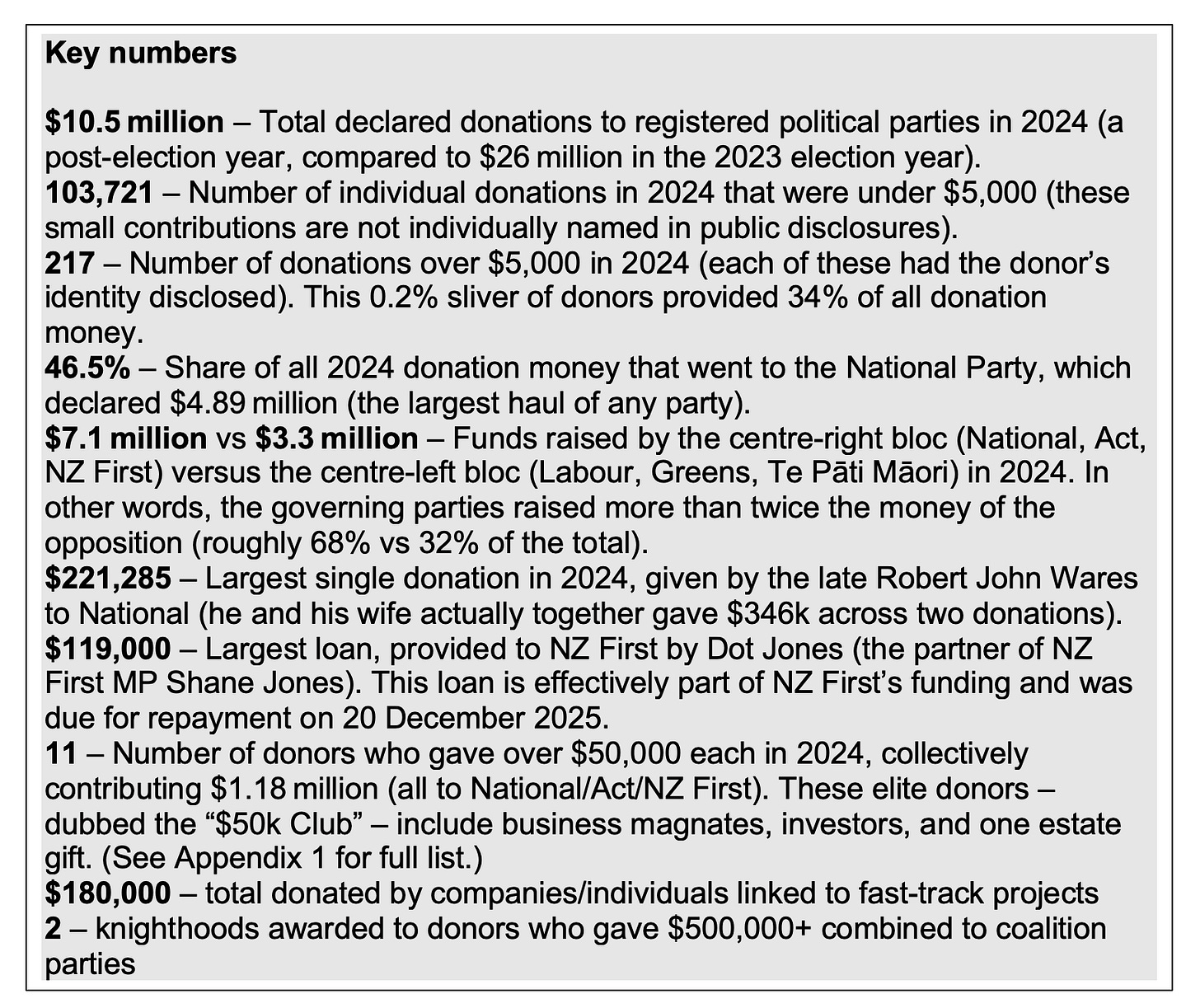

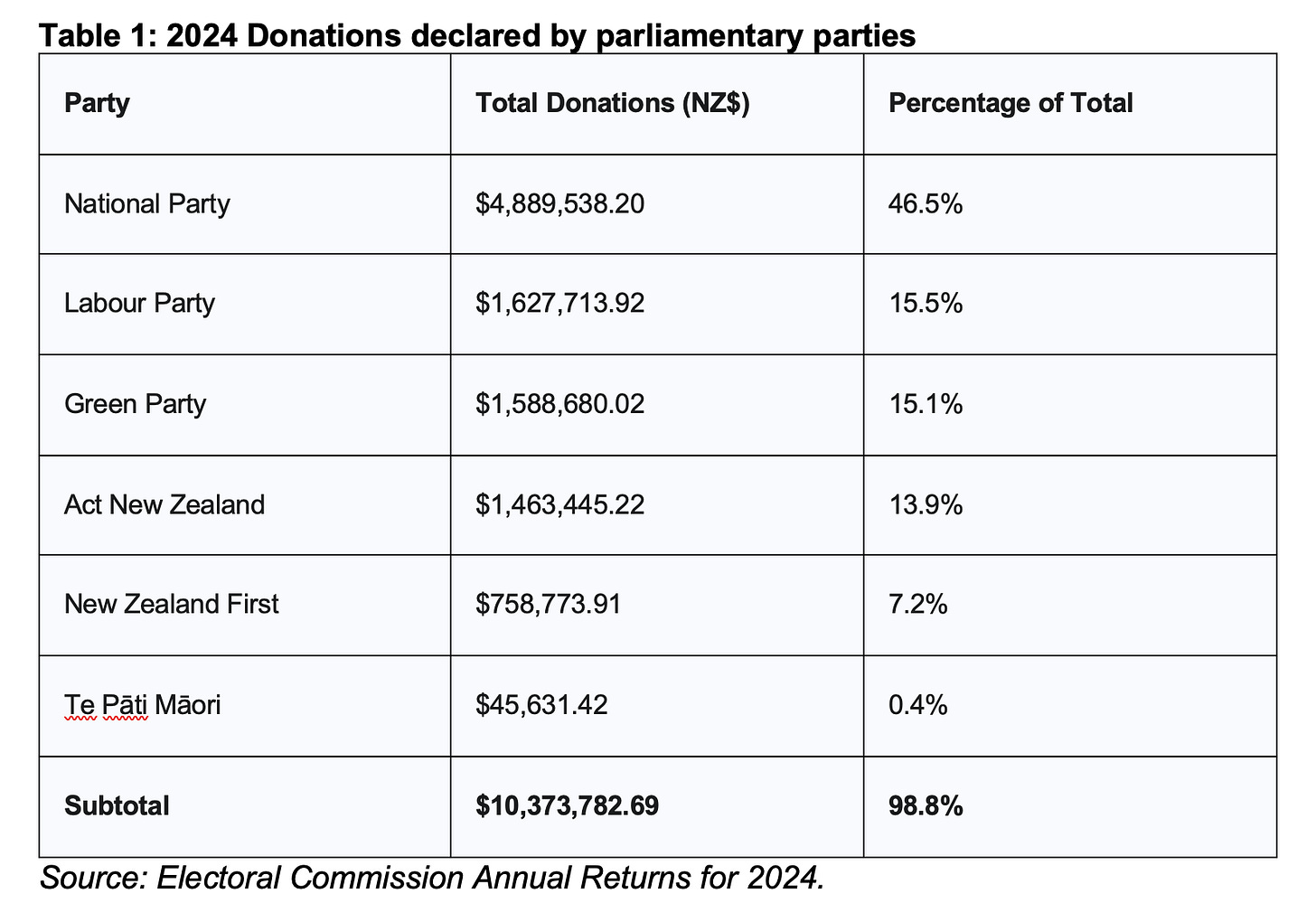

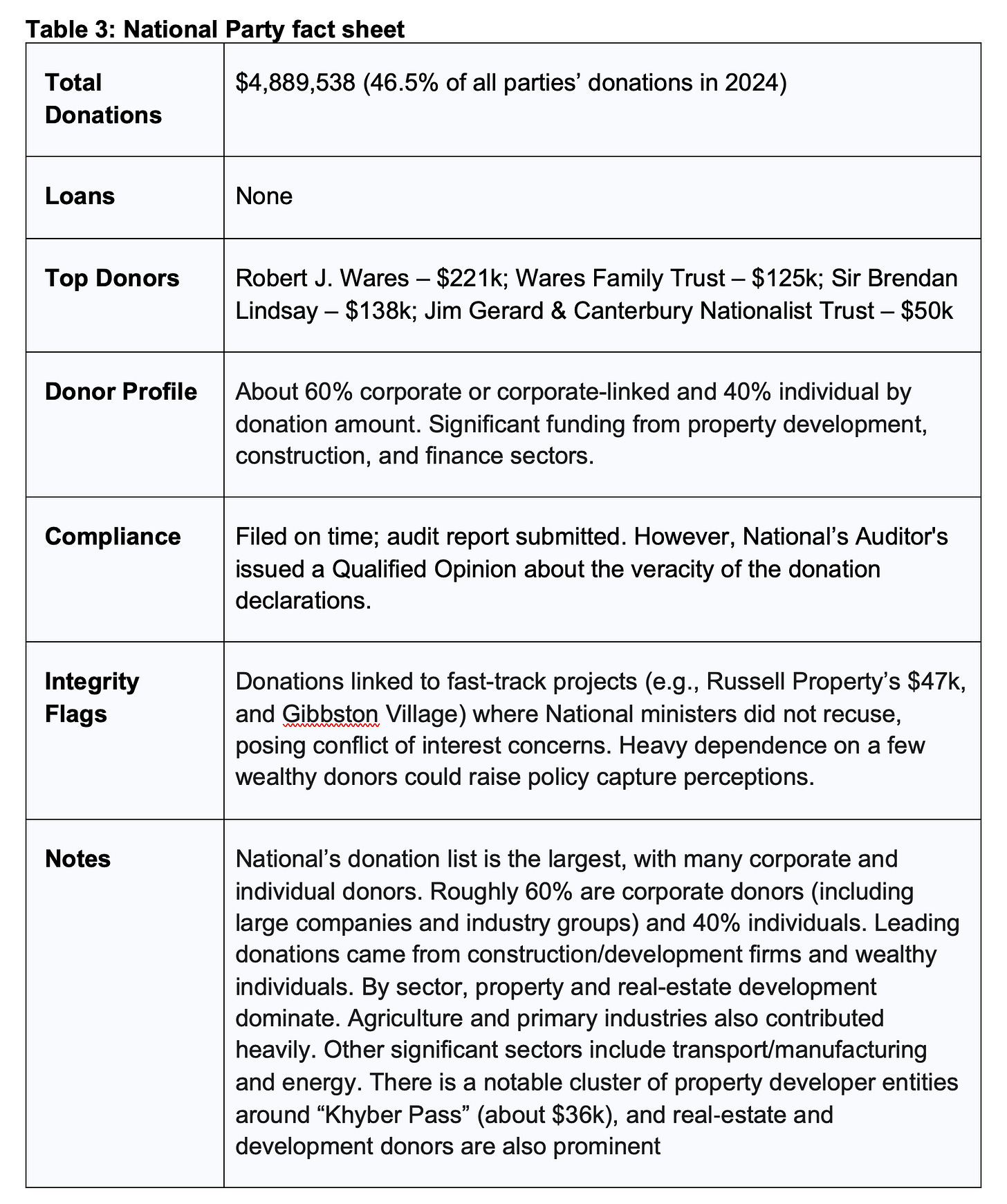

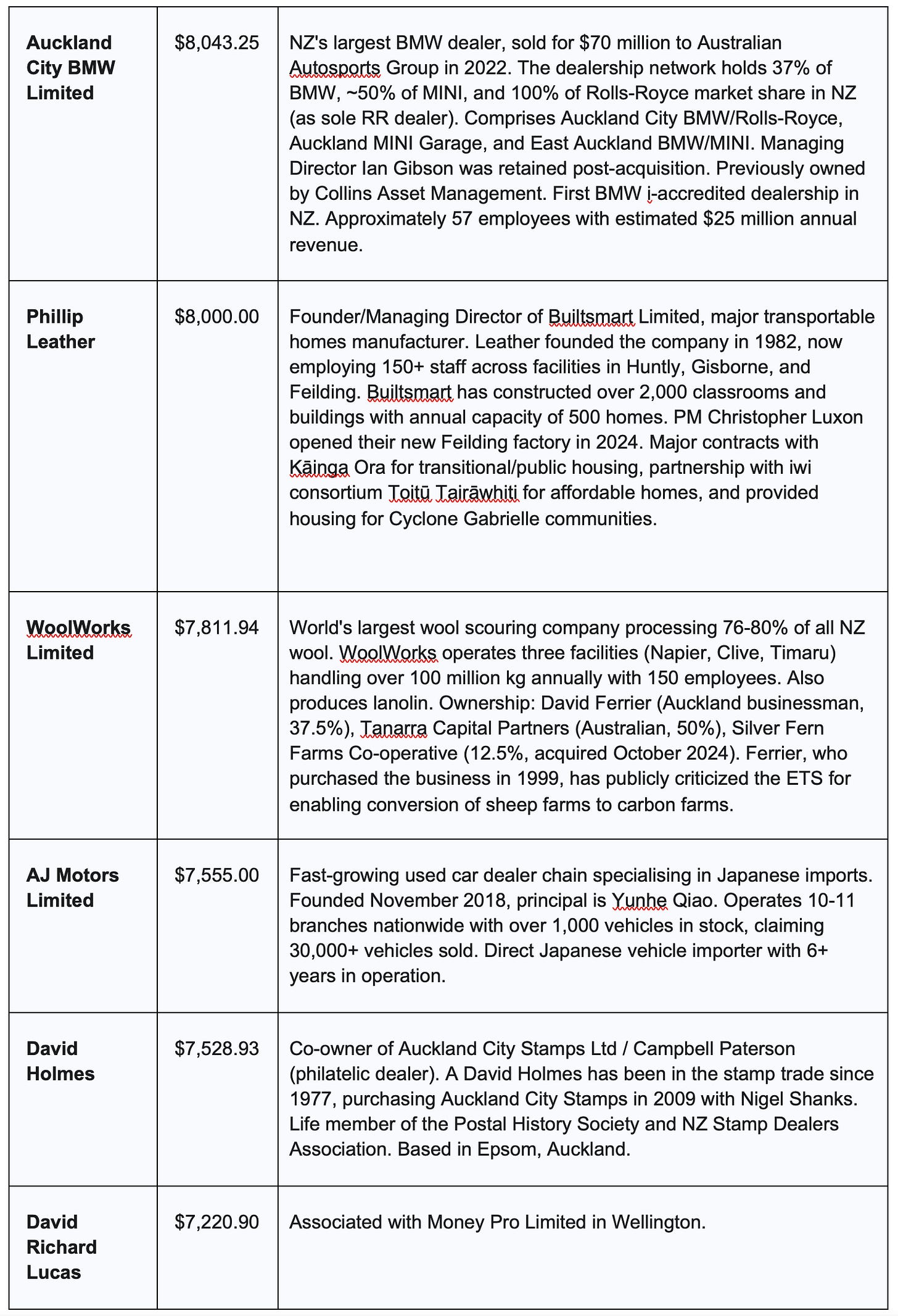

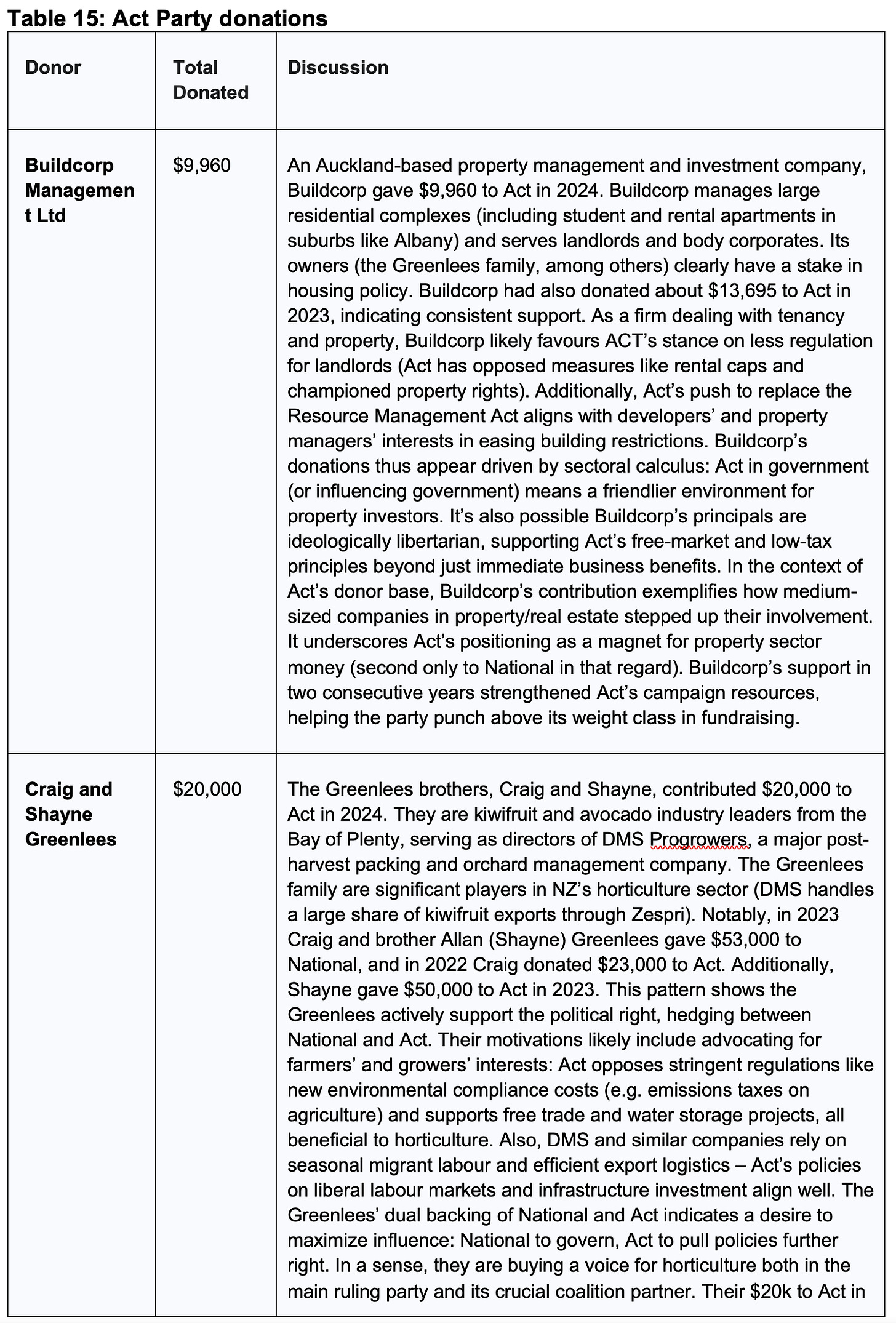

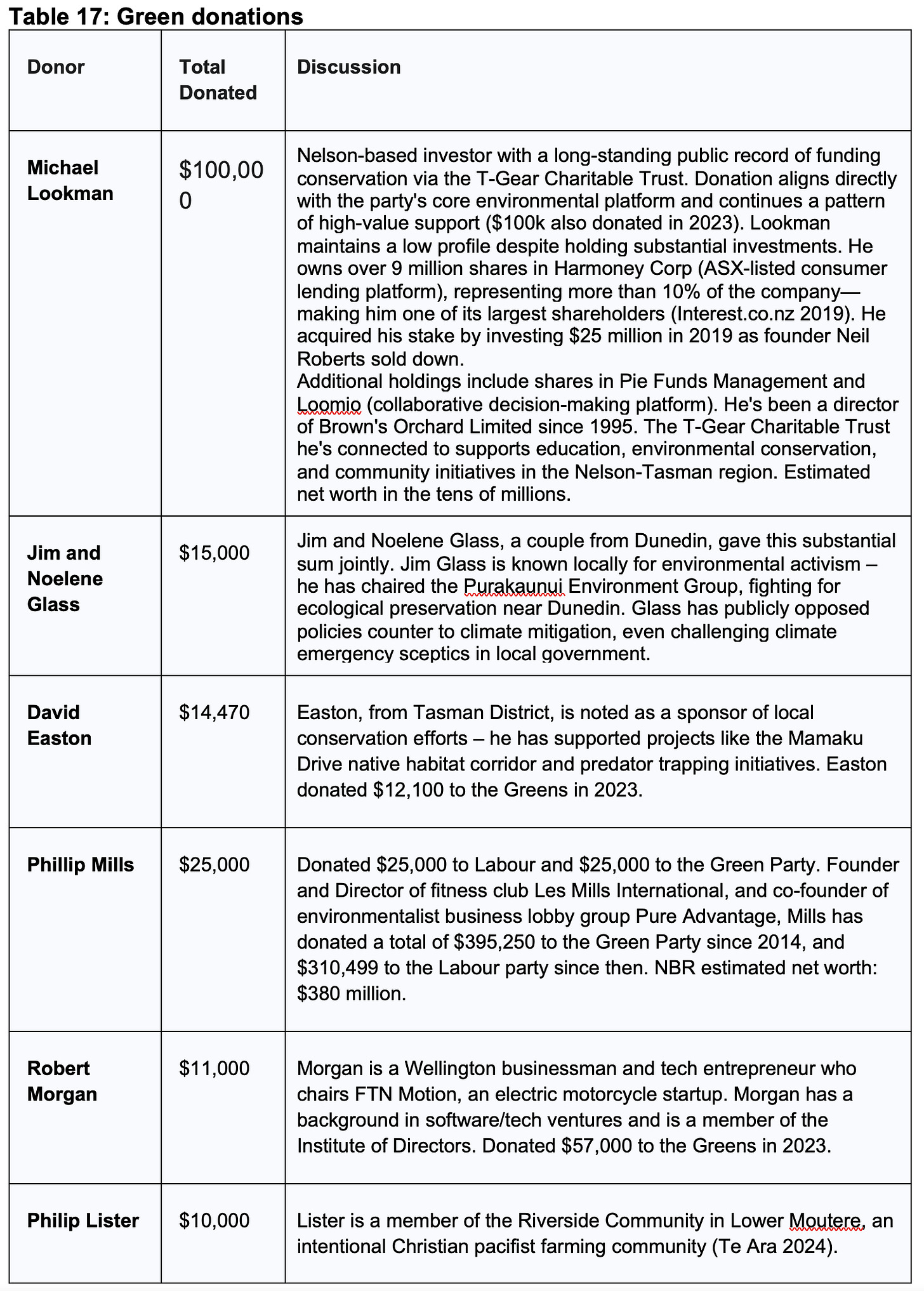

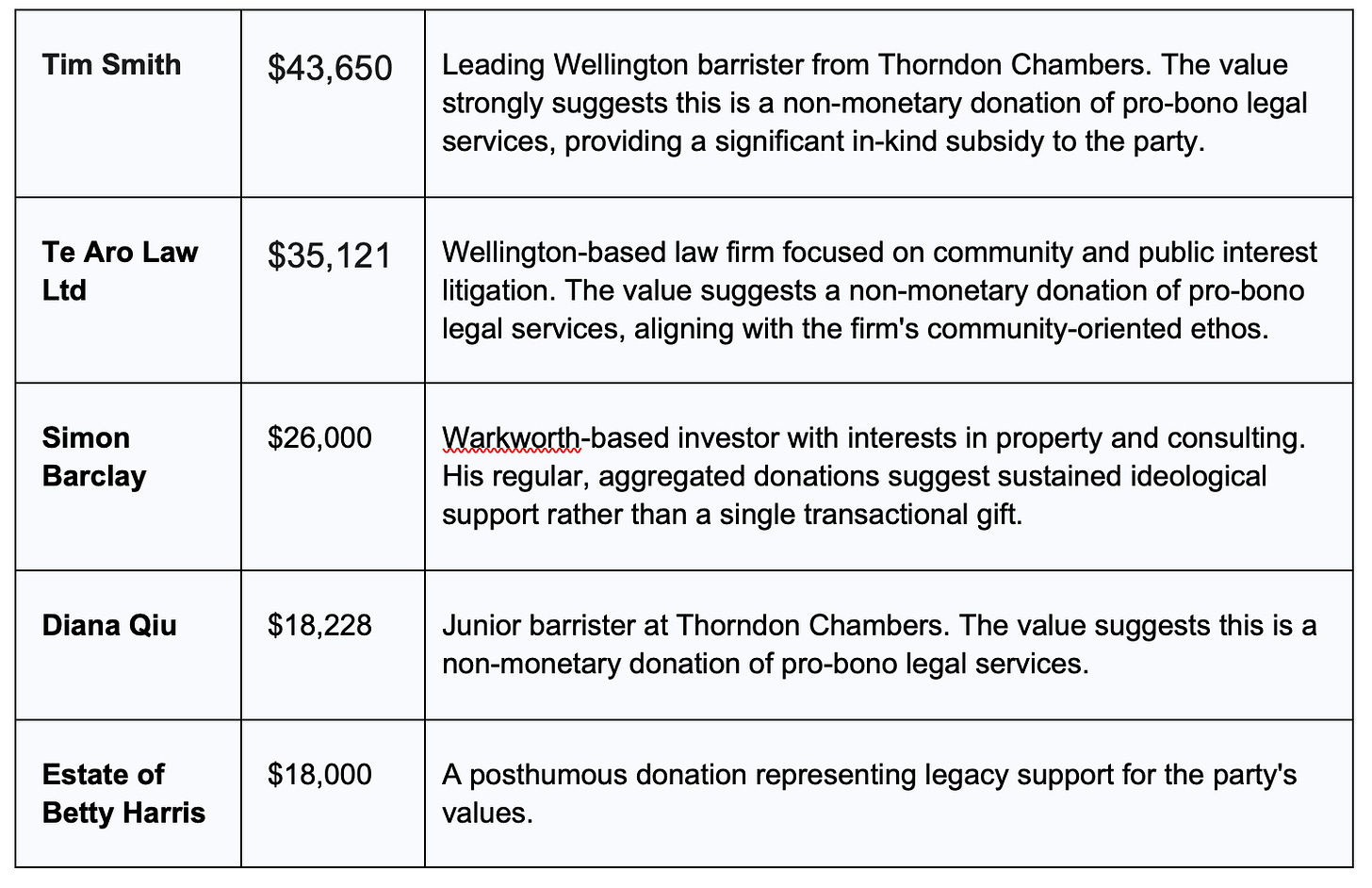

Below, in Table 1, the total donations declared by the parliamentary parties are expressed, showing how the National Party received the highest amount, taking 46.5% of all donations declared. Chart 1, further below, expresses the total differently, and includes TOP from outside of Parliament, with more detail about the types of donations received, as the data now includes information about the quantum of donations received below the declarable threshold of $5000.

2.1 Macro-level data presentation

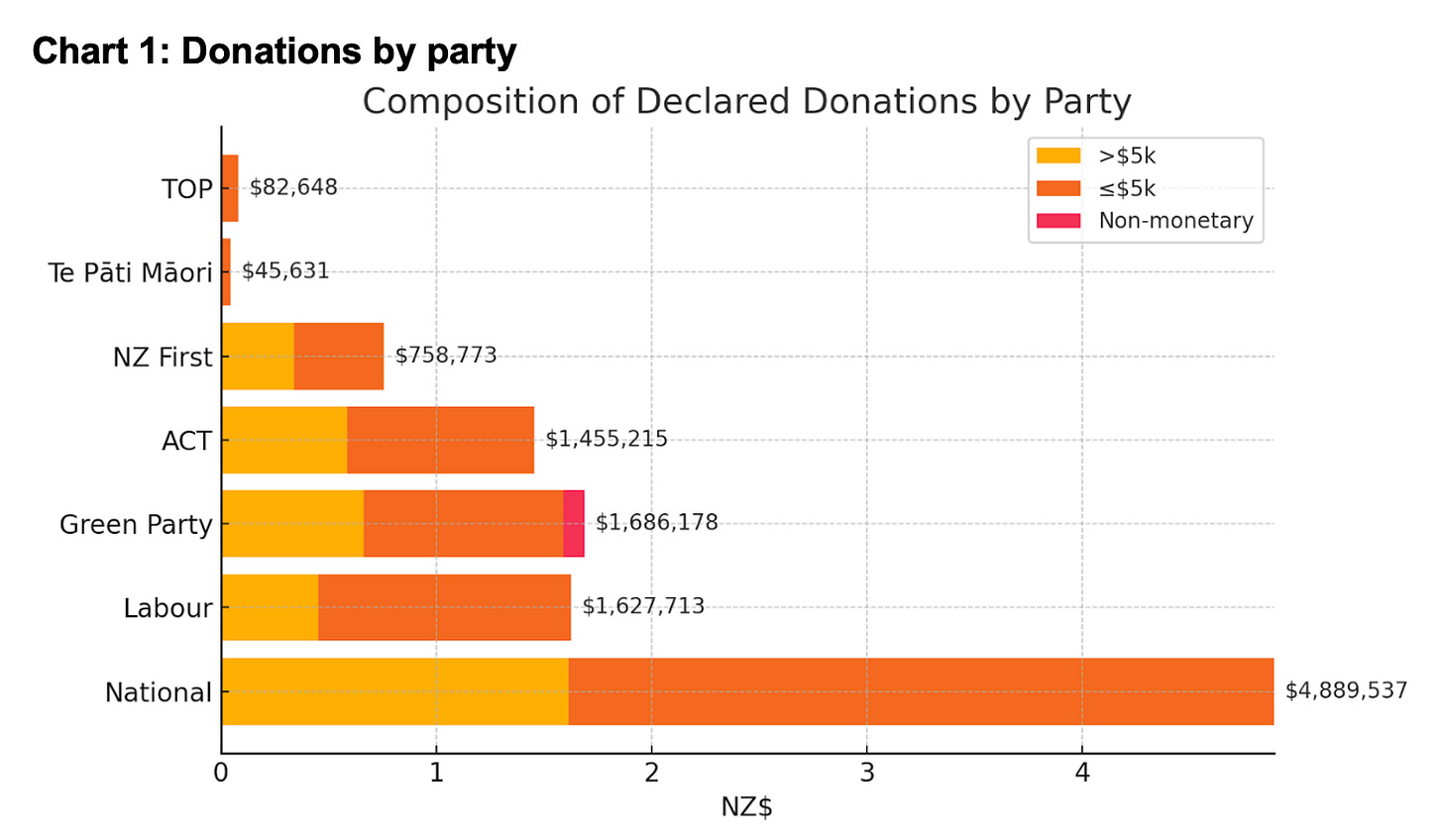

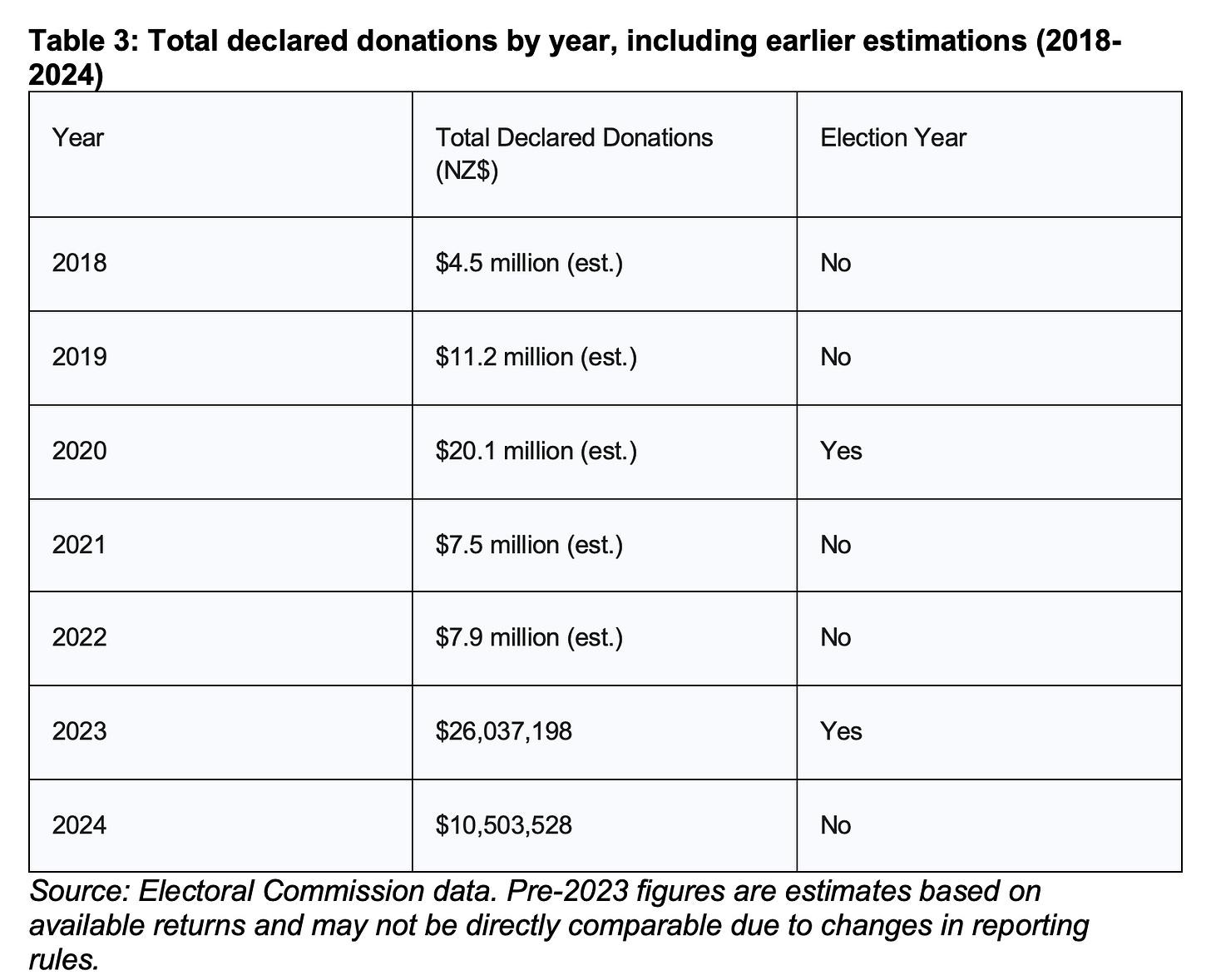

In total, New Zealand’s registered political parties declared $10.5 million in donations for the 2024 calendar year (Electoral Commission 2025). As expected, this figure is substantially lower than the $26 million declared in the 2023 general election year.

It is clear that the lower disclosure threshold has dramatically increased the quantum of donations declared, with the 2023 election year far in excess of the previous two election years. However, it is interesting to observe that 2024 returns show a higher value of declarations than previous years immediately post-election as a proportion of the election year total. 2024 saw approximately 40% of the election-year total donated, compared with 36% in 2021 and 17% in 2018.

Of this total, 94% of all funds — approximately $9.87 million — went to the seven largest parties, six of which are represented in Parliament. The National Party was the dominant recipient, securing 46% of all donated funds, a total of nearly $4.9 million (Electoral Commission 2025; Ensor 2025a).

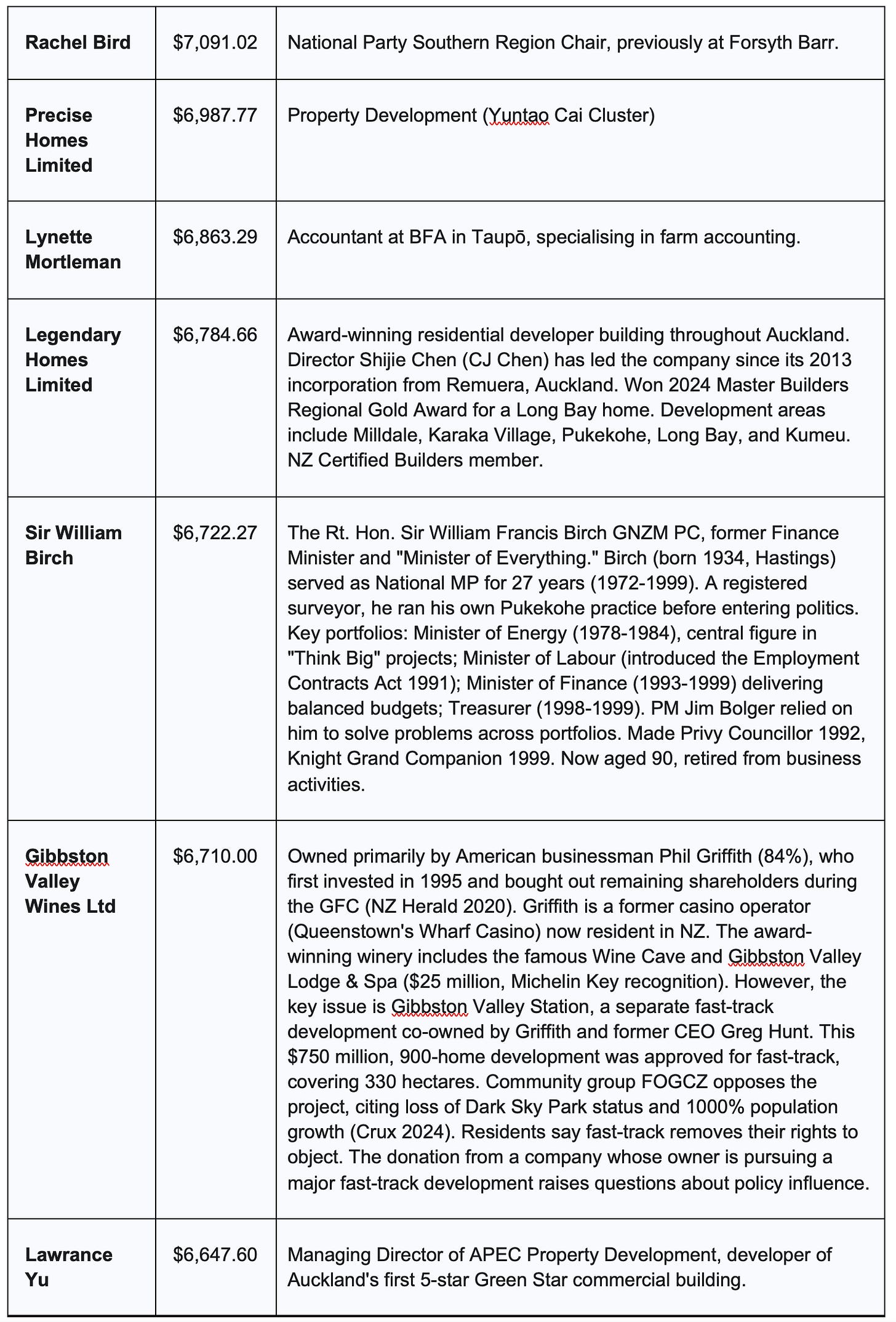

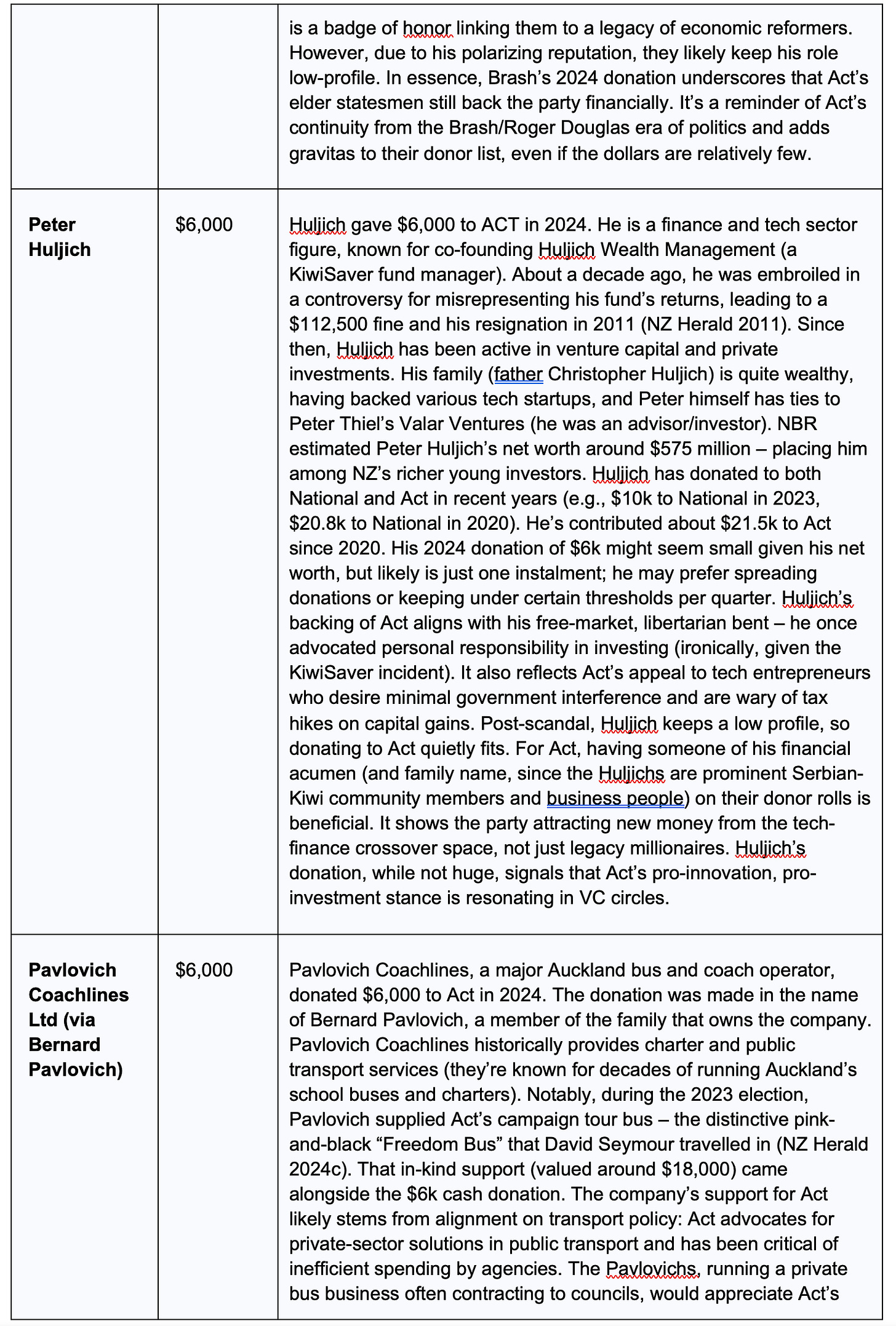

The new thresholds and reporting laws mean that a much higher volume of donations have been declared for 2024, which can’t be directly compared with earlier years. Nonetheless, the new configurations of data allow calculations to be made about what previous year totals might have been, going back to 2018. See Table 2, below, which indicates that the volume of donations has been increasing quite significantly in recent years.

2.2 Analysis of funding models: A Tale of two systems

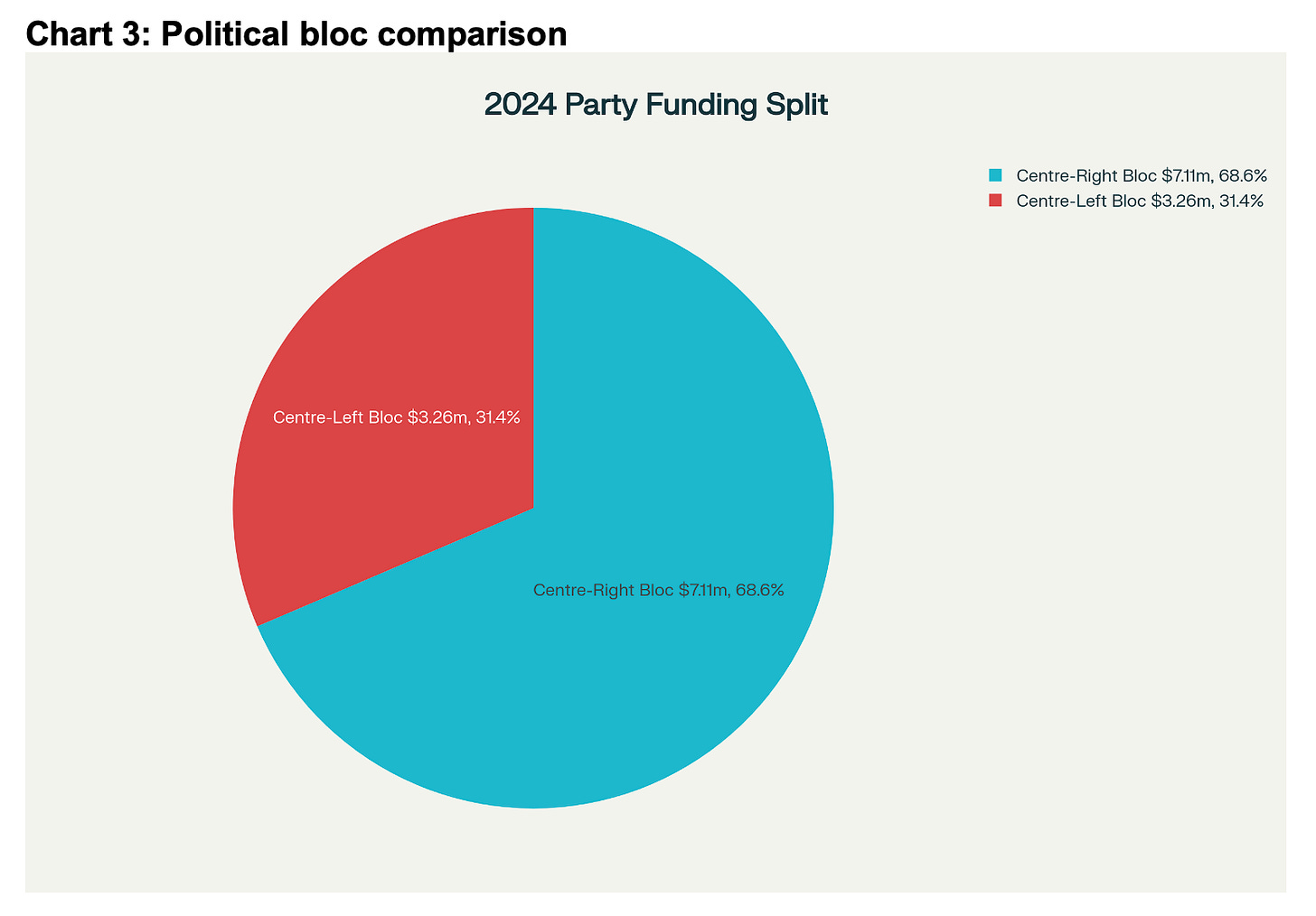

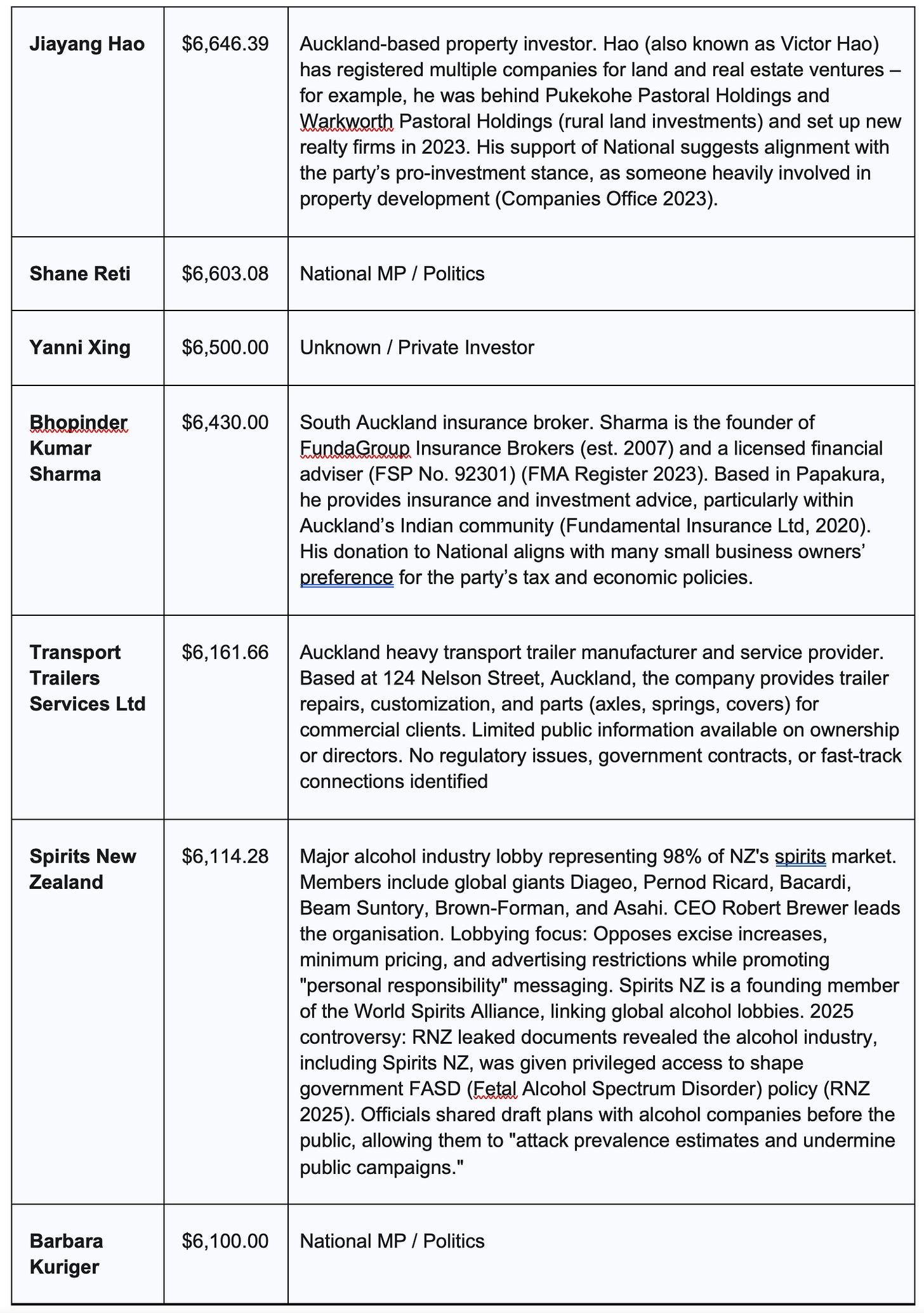

Beyond the raw numbers, the 2024 data reveals a stark bifurcation in how New Zealand’s political blocs are financed. The centre-right side of politics (National, Act and NZ First) collected $7.1 million, while the centre-left bloc (Labour, Greens, Te Pāti Māori) has raised $3.3 million. Therefore, in 2024 the centre-right’s haul was roughly double that of the centre-left.

This is not simply a matter of one side raising more money than the other; it reflects two fundamentally different models of political engagement and financial support, with profound implications for whose interests are represented in the halls of power.

2.3 The Coalition parties: A System reliant on chequebook politics

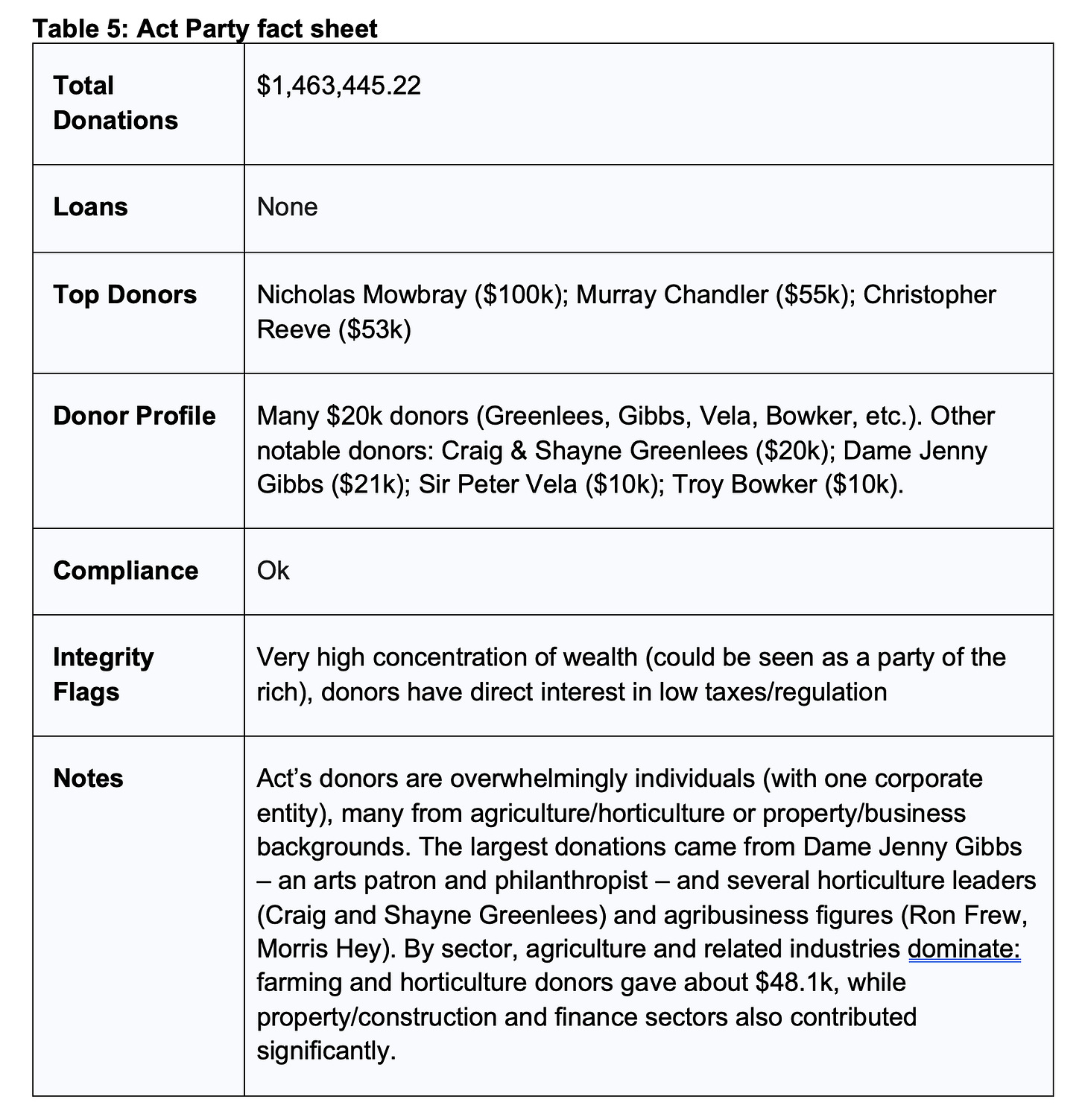

The funding model of the three governing centre-right parties (National, Act, and New Zealand First) is overwhelmingly characterised by a reliance on large donations from a narrow base of corporate entities and high-net-worth individuals. This is a transactional, business-oriented model where financial support is heavily concentrated among those with significant commercial interests.

The evidence for this is clear. All eleven of the year’s largest donations (those over $50,000) went to the parties of the Coalition Government, totalling over $1.1 million from this elite group alone. An analysis of donations since 2021 confirms this pattern, showing that contributions from the property and finance sectors flow almost exclusively to National, Act, and NZ First.

National’s donor list is approximately 60% corporate, with leading contributions from construction, development, and real estate firms. Act’s donors are primarily high-net-worth individuals from business, property, and agribusiness backgrounds. NZ First attracts significant funding from the primary and extractive industries, including mining, forestry, and transport. This is a system funded by capital.

There is also an emerging donor bloc of diaspora business networks, that the National Party in particular is utilising. National’s funding model is diversifying beyond its traditional base, to include New Zealand’s Chinese and Indian business communities, especially in terms of property, retail, manufacturing, and consulting. See the section on National Party donors later for more data on this.

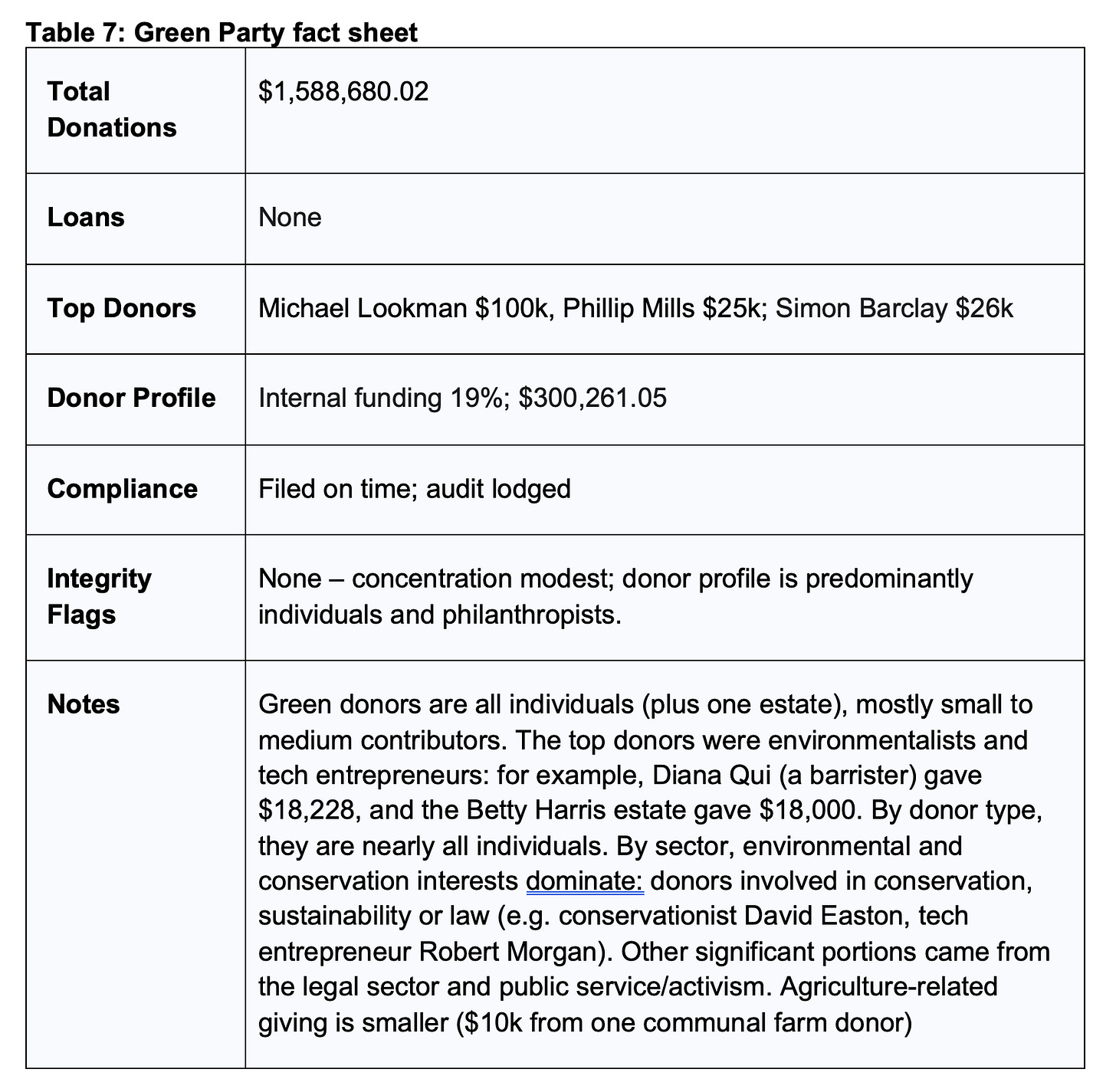

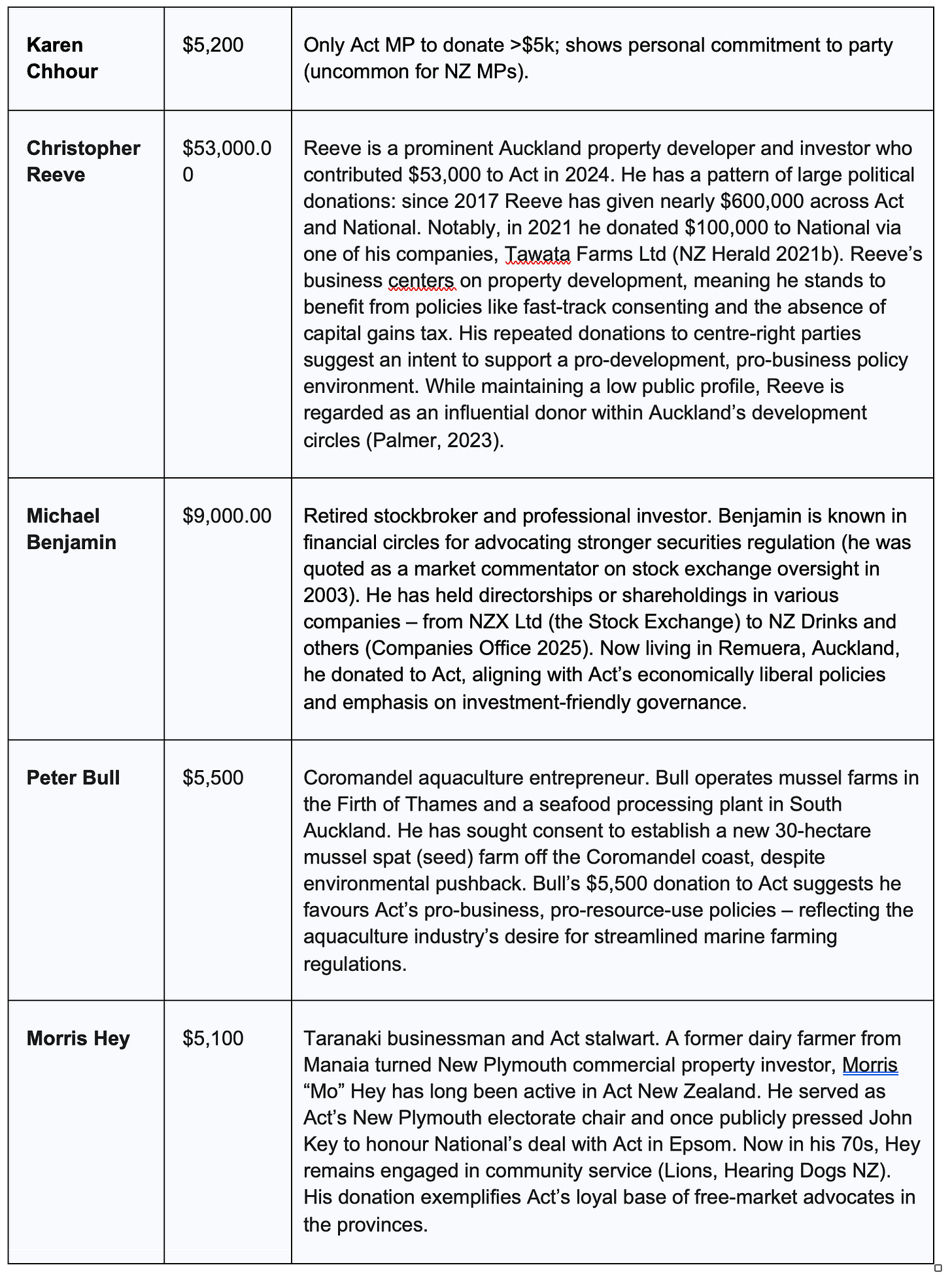

2.4 The Opposition parties: A System reliant on participation and ideology

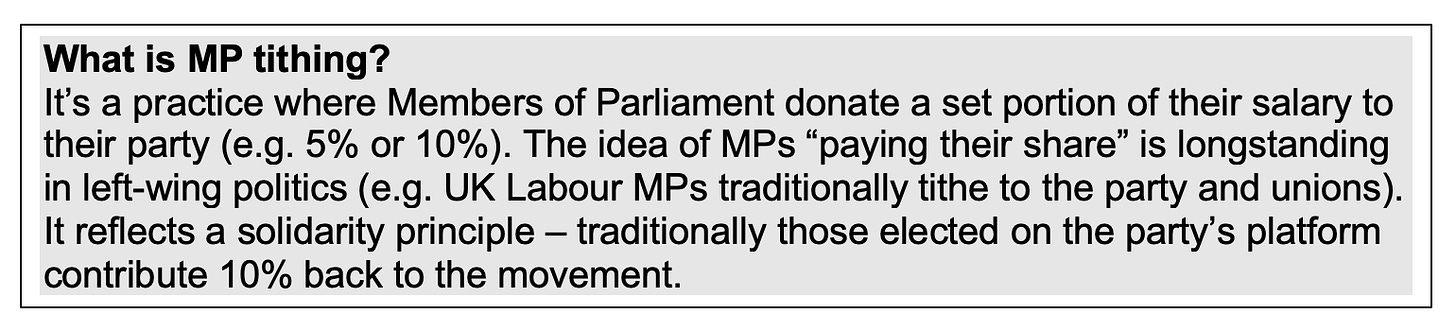

In stark contrast, the funding model of the Labour and Green parties is characterised by a broader base of smaller individual donations, supplemented by a significant and transparent system of internal tithing from their elected Members of Parliament. This is a participatory model, more reliant on mass membership and ideological alignment than on large transitions from vested interests.

MP donations to these parties are considerable. Last year, tithed donations from MPs comprised 15.6% of Labour’s total declared contributions and 18.9% of the Greens’ total (see section 2.5 below).

The donor lists of Labour and the Greens are dominated by individuals, including former politicians, academics, philanthropists, and environmental activists, rather than large corporations. This is underscored by the near-total absence of significant business donations to the Labour Party since 2021, a dramatic shift from previous eras when Labour was more successful in fundraising from businesses (Brown 2023). This is now a system funded by activists, members, and labour.

This bifurcation is more than a statistical curiosity. It suggests that the two sides of the political spectrum are responsive to fundamentally different constituencies, not just at the ballot box, but in their day-to-day financing. The Government is financially beholden to the interests of business and wealth, while the opposition is financially reliant on its members and ideological supporters. This dynamic shapes not only their policy platforms but also who gets a seat at the table when crucial decisions are made.

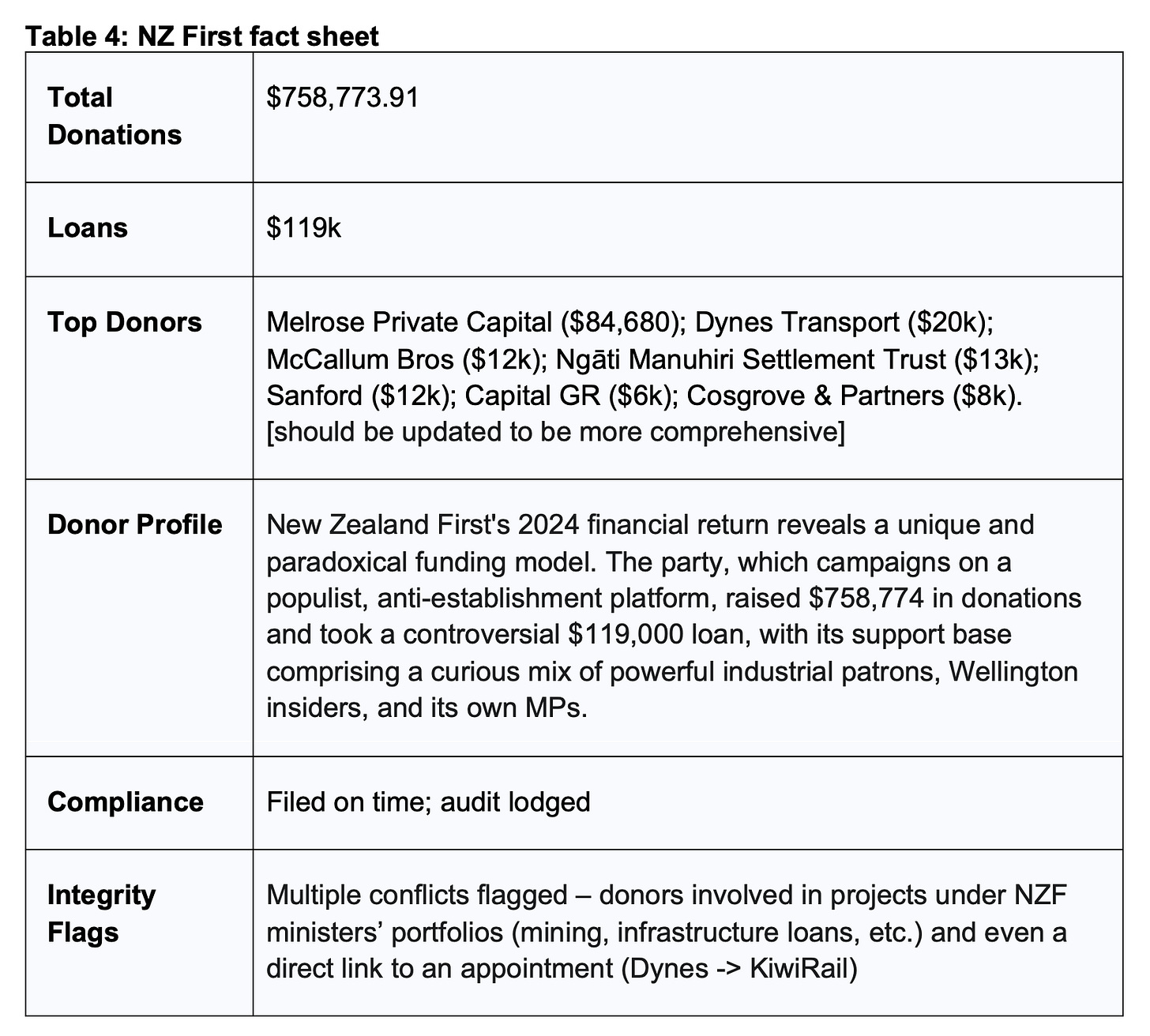

Of course, not all funding is neatly siloed by ideology – some wealthy individuals play all sides presumably to gain influence. For example, Wellington businessman Troy Bowker has given money to Act, NZ First, and even a Labour MP, presenting an interesting case of a donor hedging bets (Hurley 2022a; Hurley 2022b; Cook 2021).

However, more typically, when donors spread their bets, they tend to stay within one of the ideological blocs. For instance, billionaire Graeme Hart has donated $700,000 to right-wing parties over 2023 and 2024, in what looks like “strategic diversification”, spending $400,000 on National, $200,000 on Act, and $100,000 on NZ First (RNZ 2023). And as discussed later, Hart does this using both personal donations and a corporate vehicle (Rank Group).

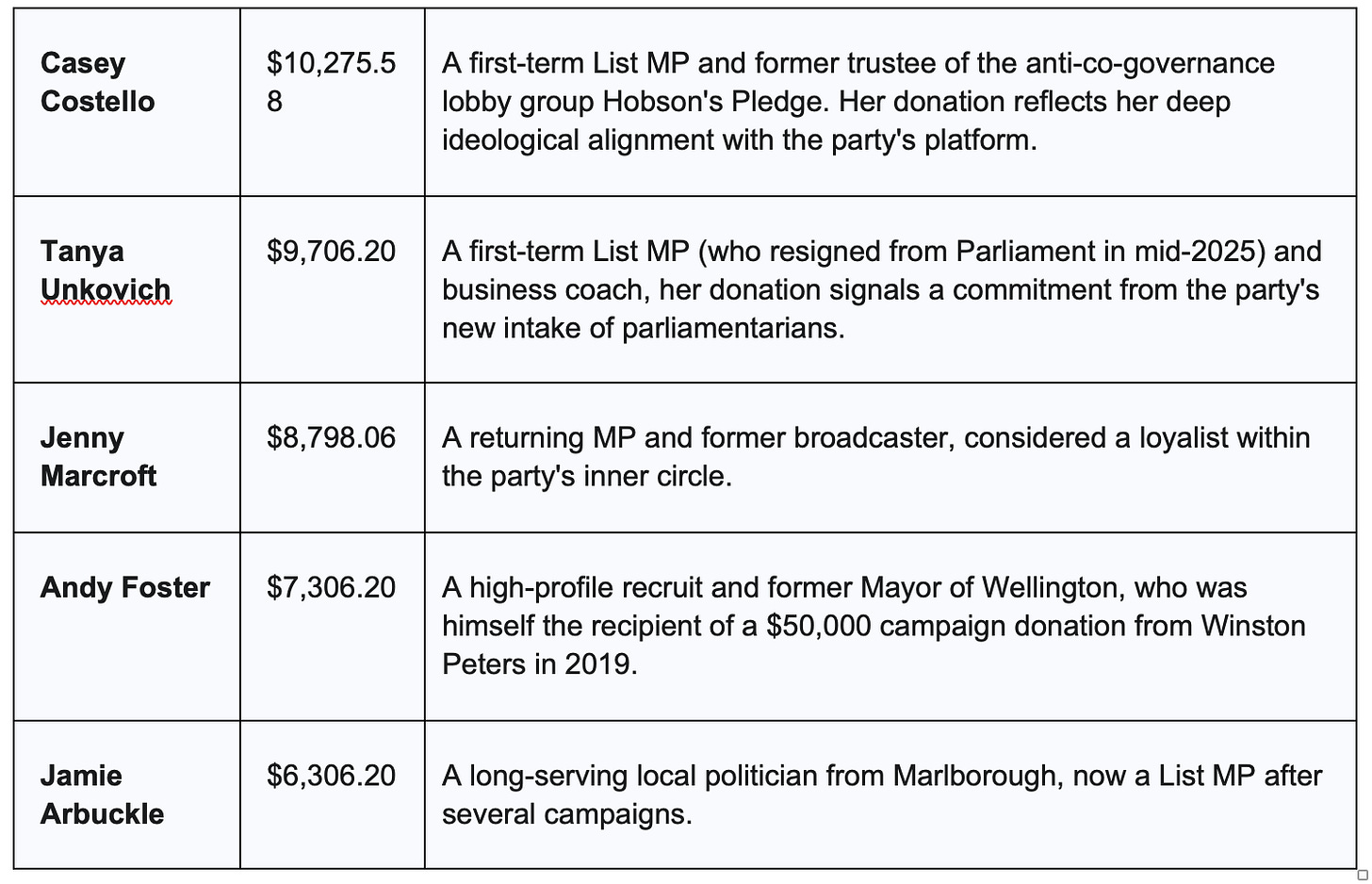

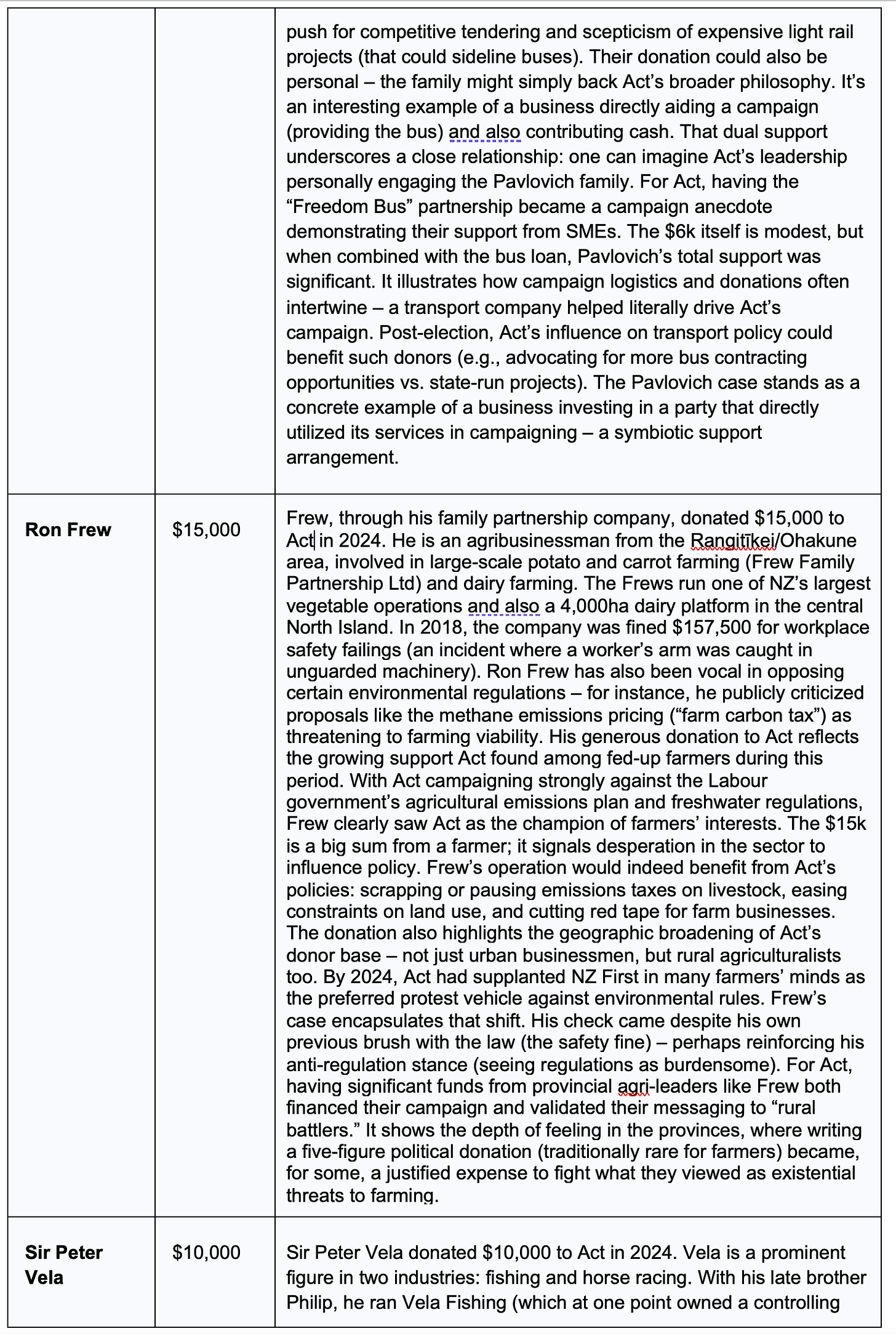

2.5 MP tithing

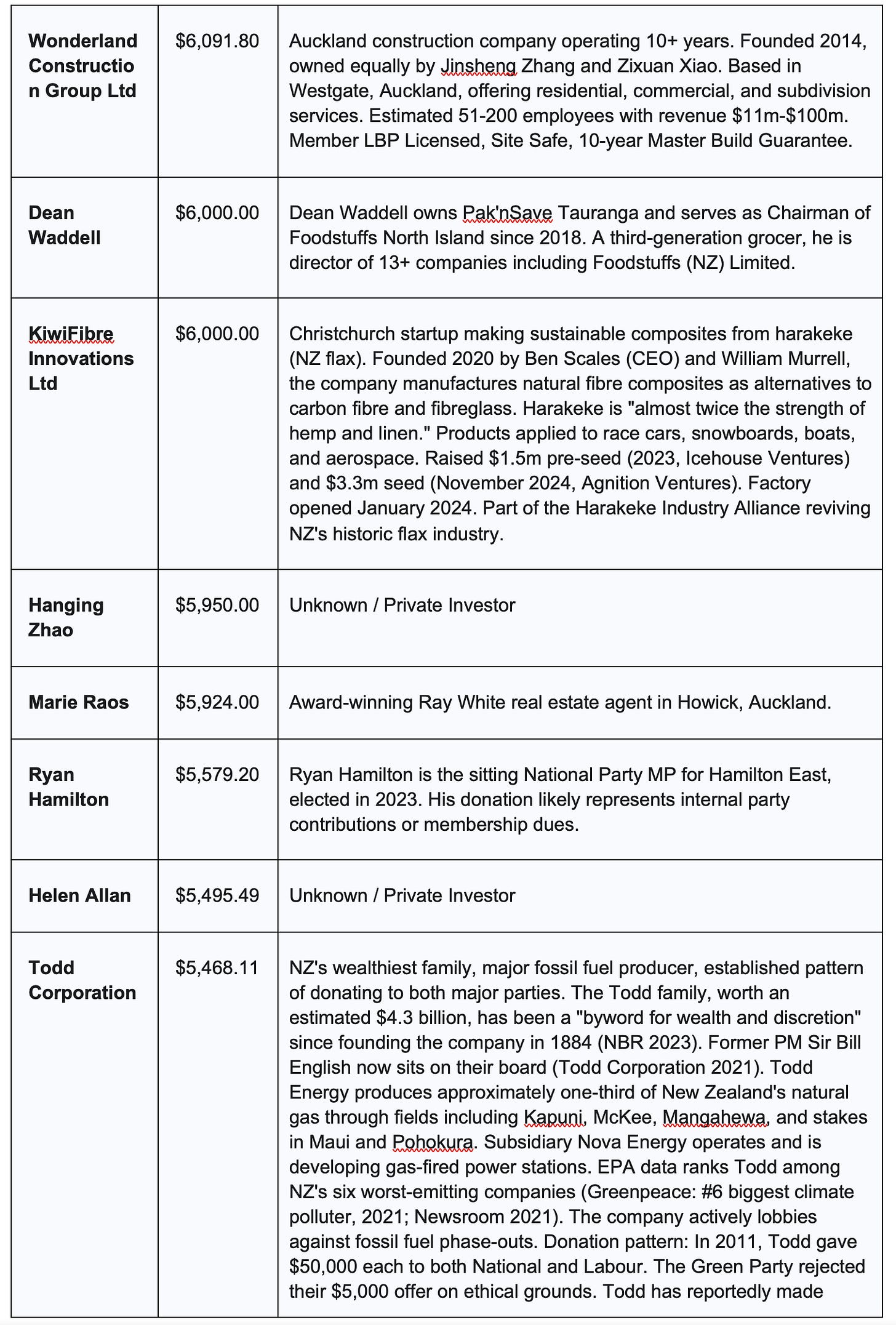

Both the Green Party and Labour Party require their MPs to contribute a share of their parliamentary salary back to the party (a practice often referred to as “tithing”). Green MPs appear to tithe 10%, and Labour MPs 5% (Collins 2010; Wikipedia 2025). New Zealand First MPs other than Winston Peters and Shane Jones also appear to tithe 5%.

For Labour and the Greens, last year these tithed donations comprised 15.6% and 18.9% of their annual contributions – that’s $253,923 for Labour, and $300,261 for the Greens.

NZ First received donations from a number of its MPs in way that suggests some form of tithing might be used. Over $42,000 was received from five of the caucus, ranging from about $6,300 to $10,300. For most MP donors, the amounts were received in the form of regular monthly payments, which suggests a form of tithing. However, in the past, NZ First has also been known to charge its candidates for the party’s overall general election expenditures, requiring repayments after the election, regardless of electoral success.

National, Act and Te Pati Māori do not appear to tithe, although four National MPs – Shane Reti, Dana Kirkpatrick, Tim Costley and Carlos Cheung – made donations. The largest donation was Cheung’s $20,399.06. We have no visibility of MPs making contributions below the $5000 threshold.

The proportion of the tithing payments as donations for the Greens, Labour and NZ First can be seen in Chart 6, below, which breaks each party’s total donations amount into the proportion of funds that come from large ($5000+) donations, those below that figure, and tithes from MPs.

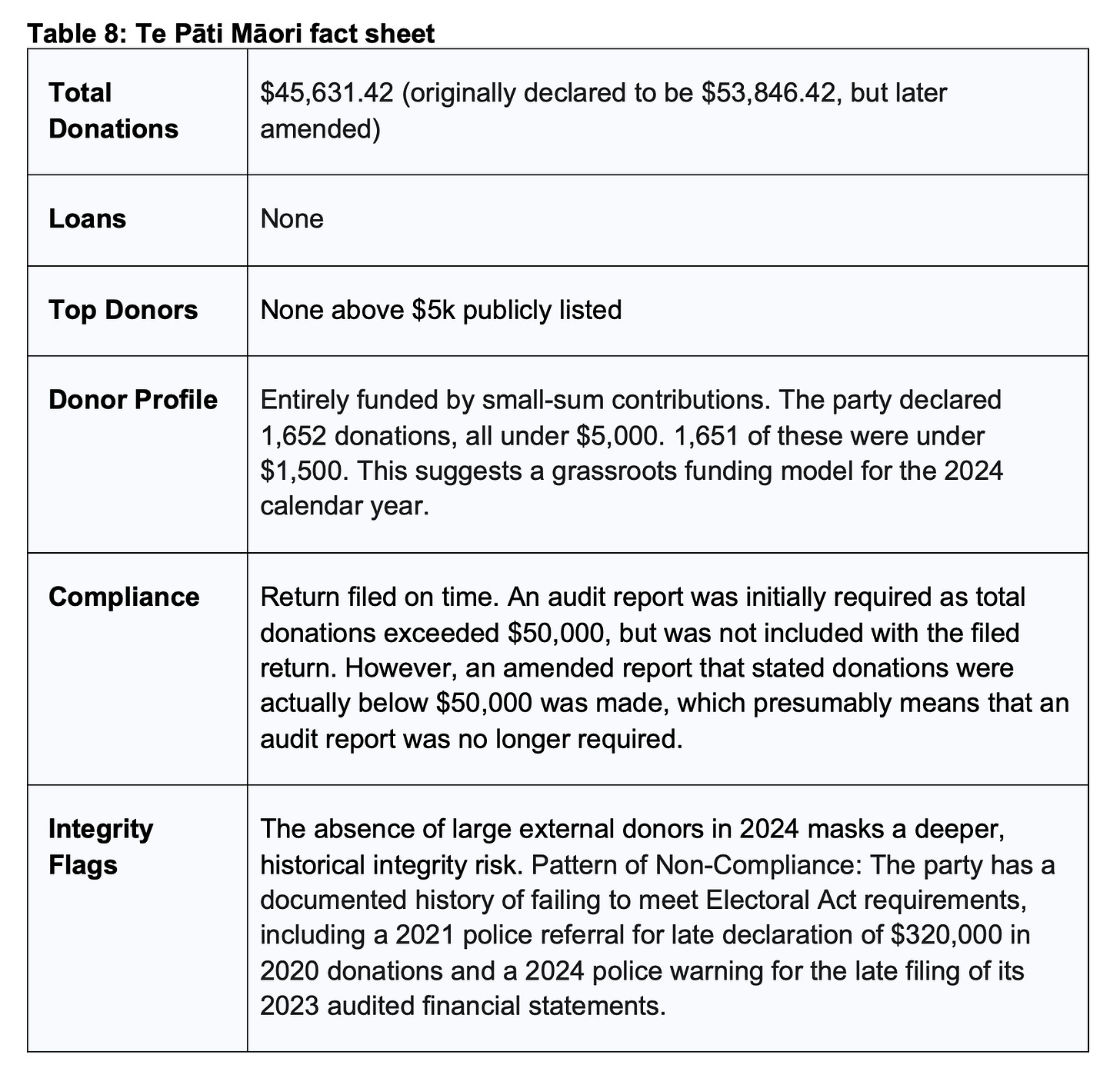

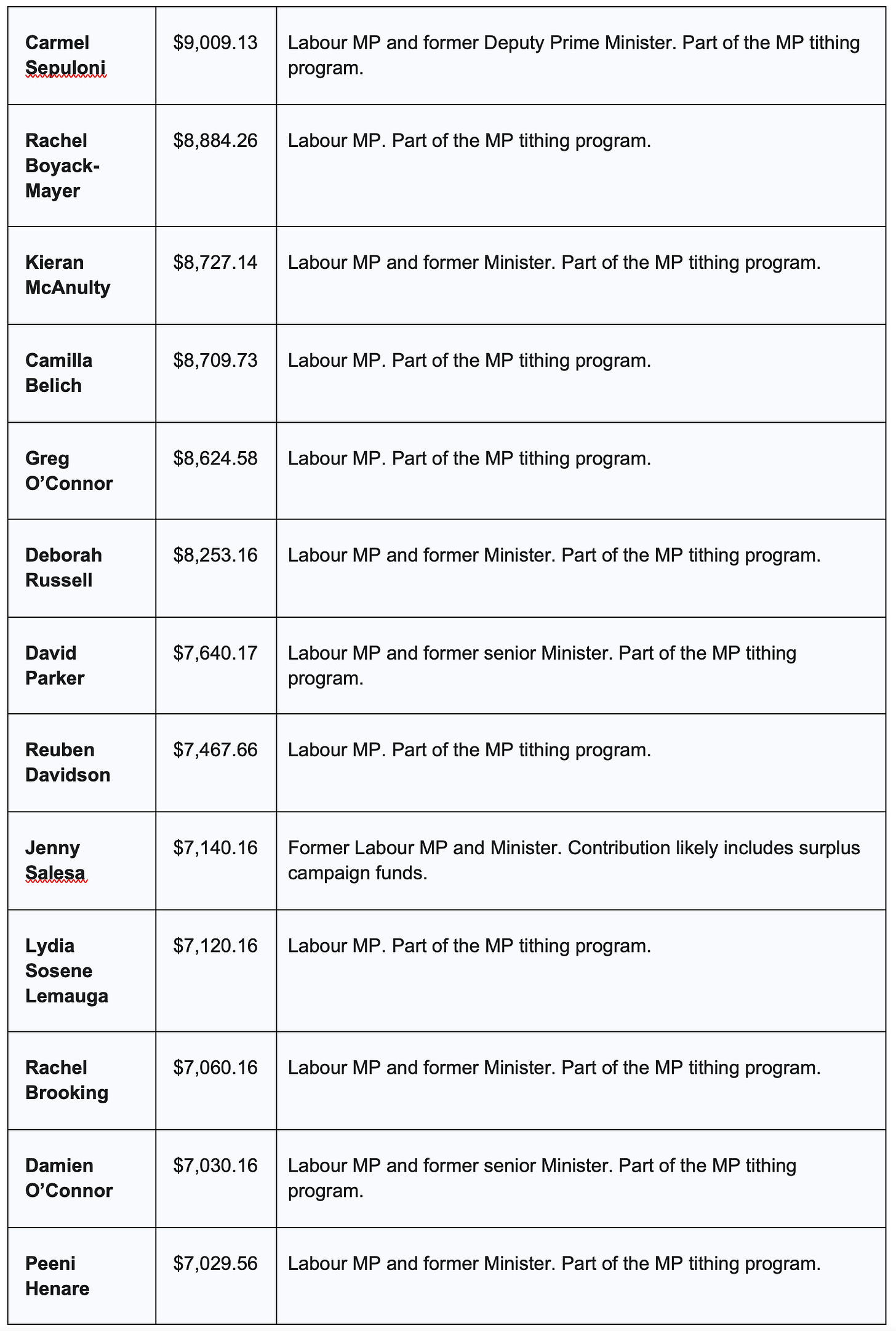

2.6 Former politicians

Beyond wealthy businesspeople there are always other figures that give generous donations – especially former MPs and other elected politicians. In 2024, Labour received $20k from former Auckland Mayor Dick Hubbard, $11k from former prime minister Helen Clark, and $17,912 from former Labour MP and Cabinet Minister Pete Hodgson (who has now donated a total of $59,736 to Labour since 2022).

National has received $50k from former National MP Jim Gerard QSO via the Canterbury Nationalist Trust. Former Deputy PM and senior Cabinet Minister Bill Birch donated $6,980.

Act received a $6,980 donation from Don Brash, who is both a former leader of that party (2011), as well as a former leader of National (2003–2006).

NZ First has received donations from lobbying firms associated with former MPs. Clayton Cosgrove’s lobbying firm Cosgrove & Associates donated $8,000 to New Zealand First (following a similar donation in the previous year). And after former New Zealand First MP Fletcher Tabuteau joined the lobbying firm Capital Government Relations Ltd, they gave $6,000 to New Zealand First (more about this in Section 3.4).

All these donations reinforce that even prominent public figures participate in donations – but in these cases on the moderate end, compared to corporate donors.

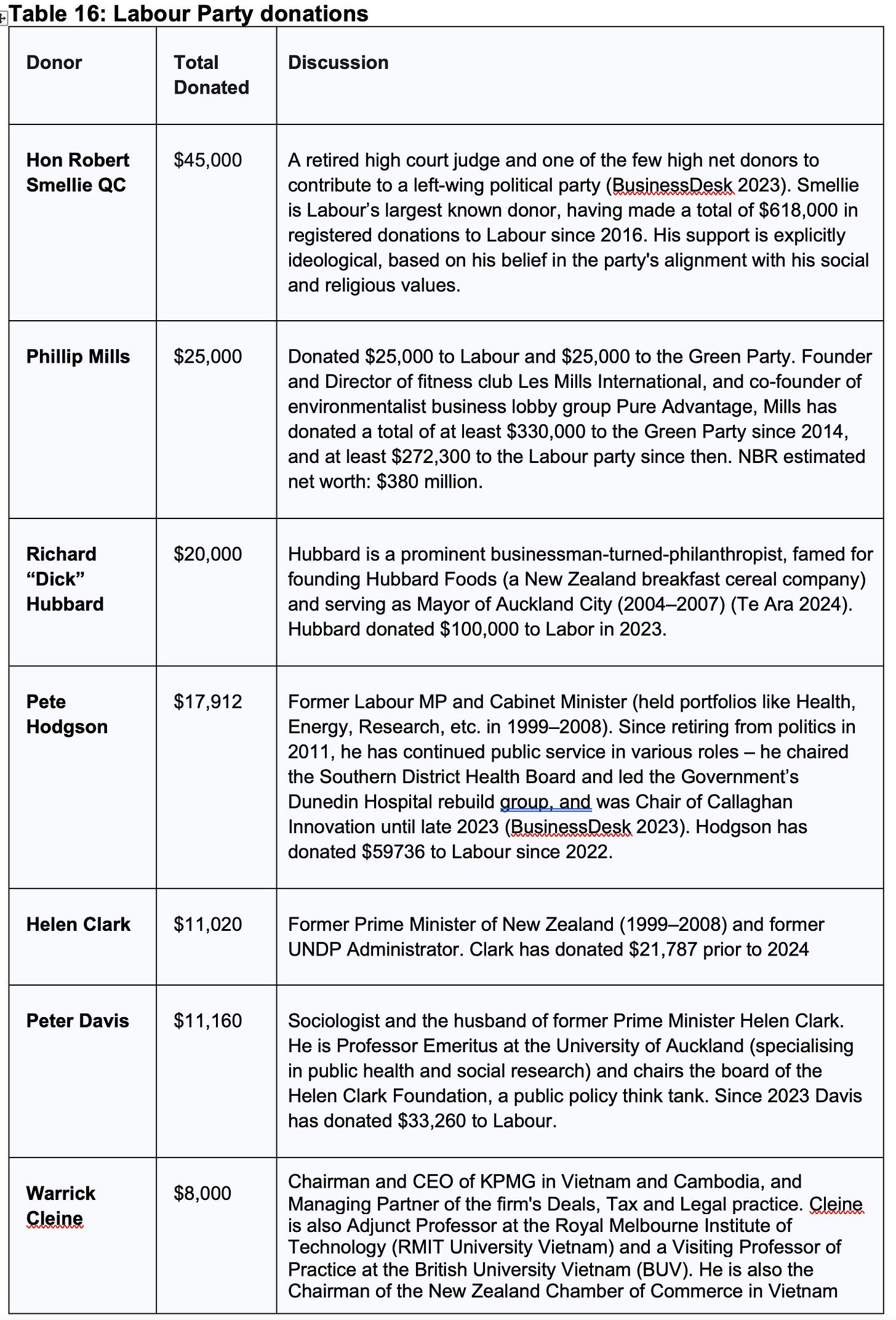

Section 3: The Donor class: Mapping the networks of influence

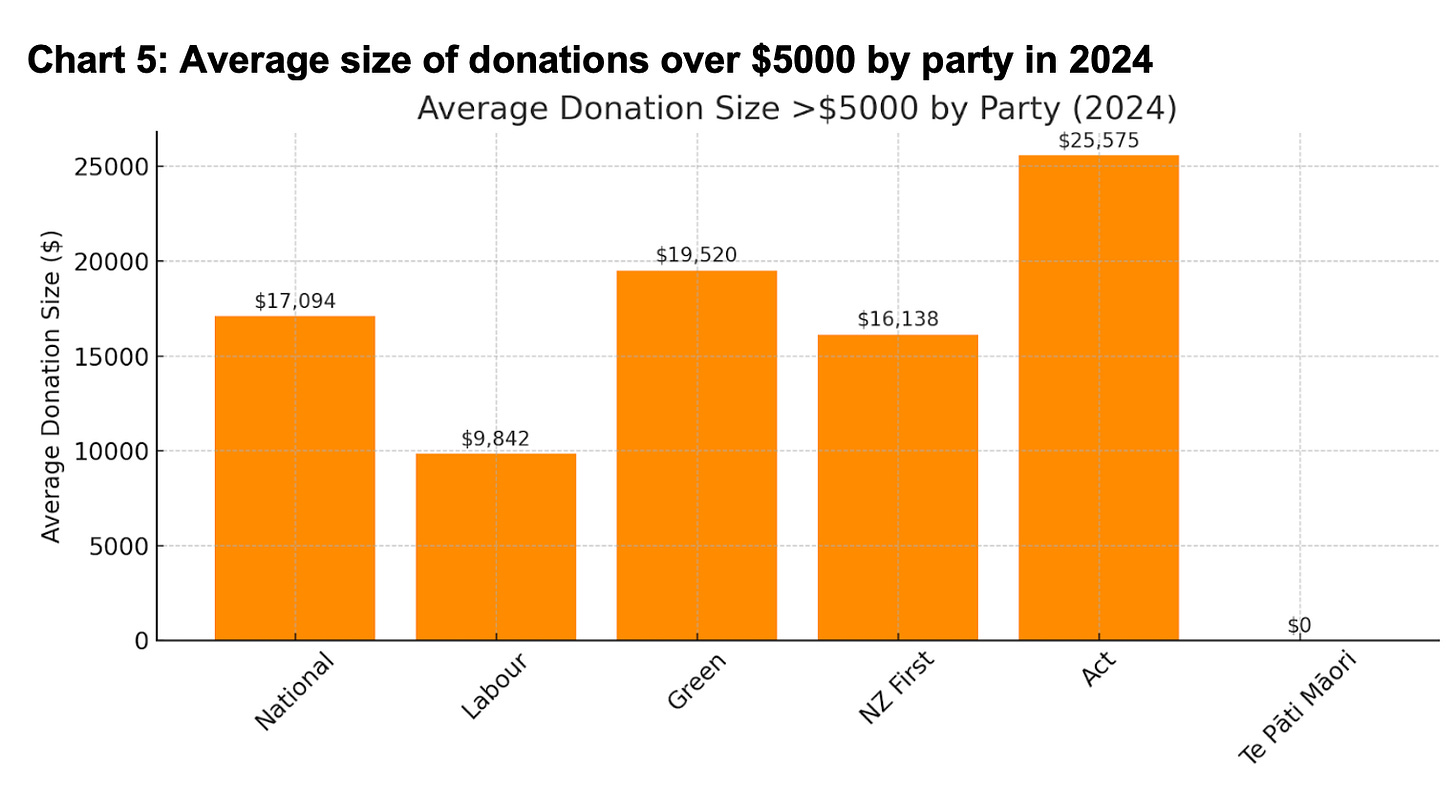

Last year there were 217 registered donations to the parliamentary political parties that were greater than $5000, and there were 103,721 donors whose contributions were below the $5000 threshold. The donors who gave more than $5000 therefore comprise just 0.2% of the total donors but contributed 34% of the total amount donated.

Looking specifically at the declared donations above the $5000 threshold, it is apparent that the size of these donations varied considerably between parties. As Chart 5 below shows, while the average donation above the disclosure threshold for Labour was just under $10,000, for the Act Party it was well over $25,000.

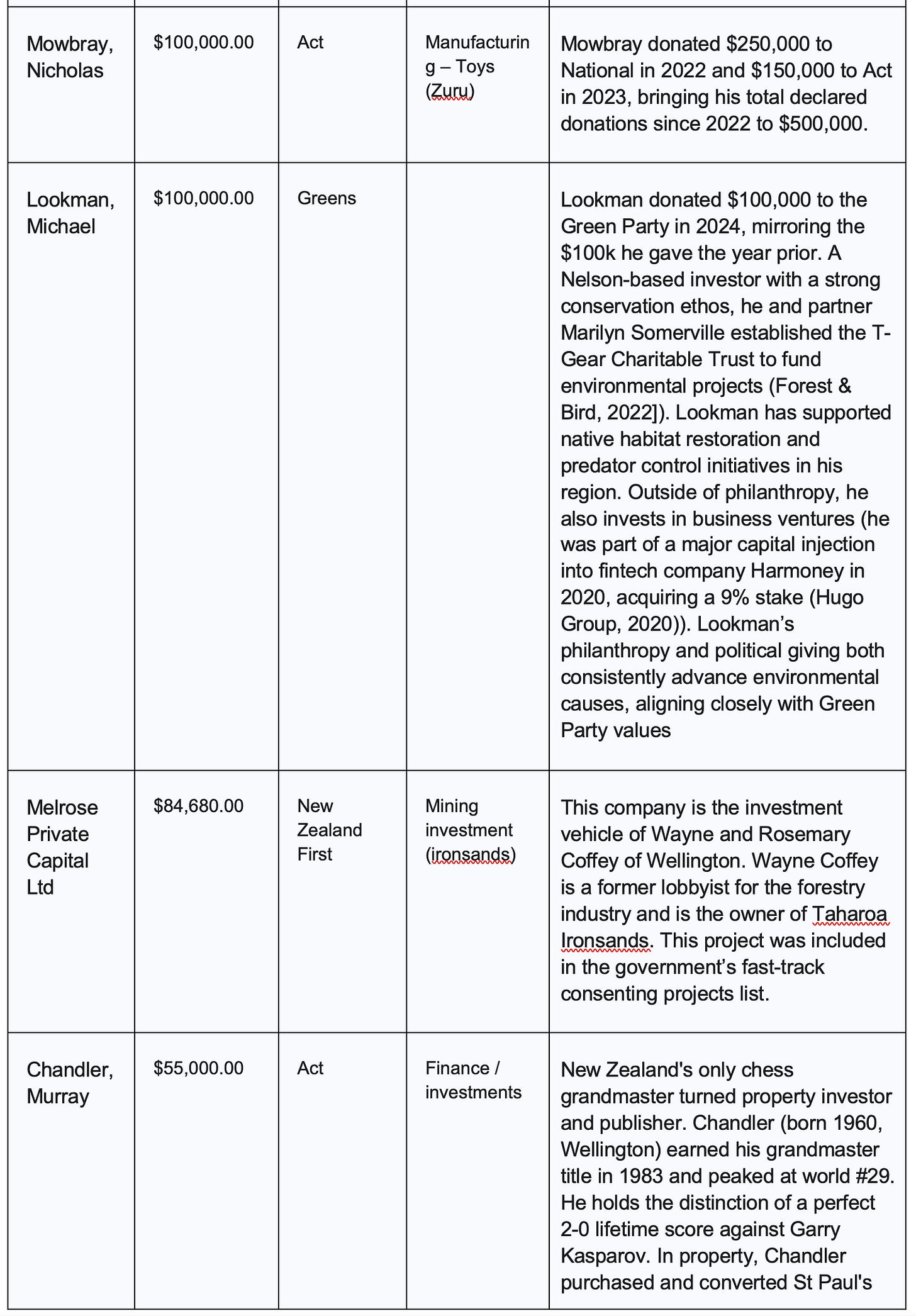

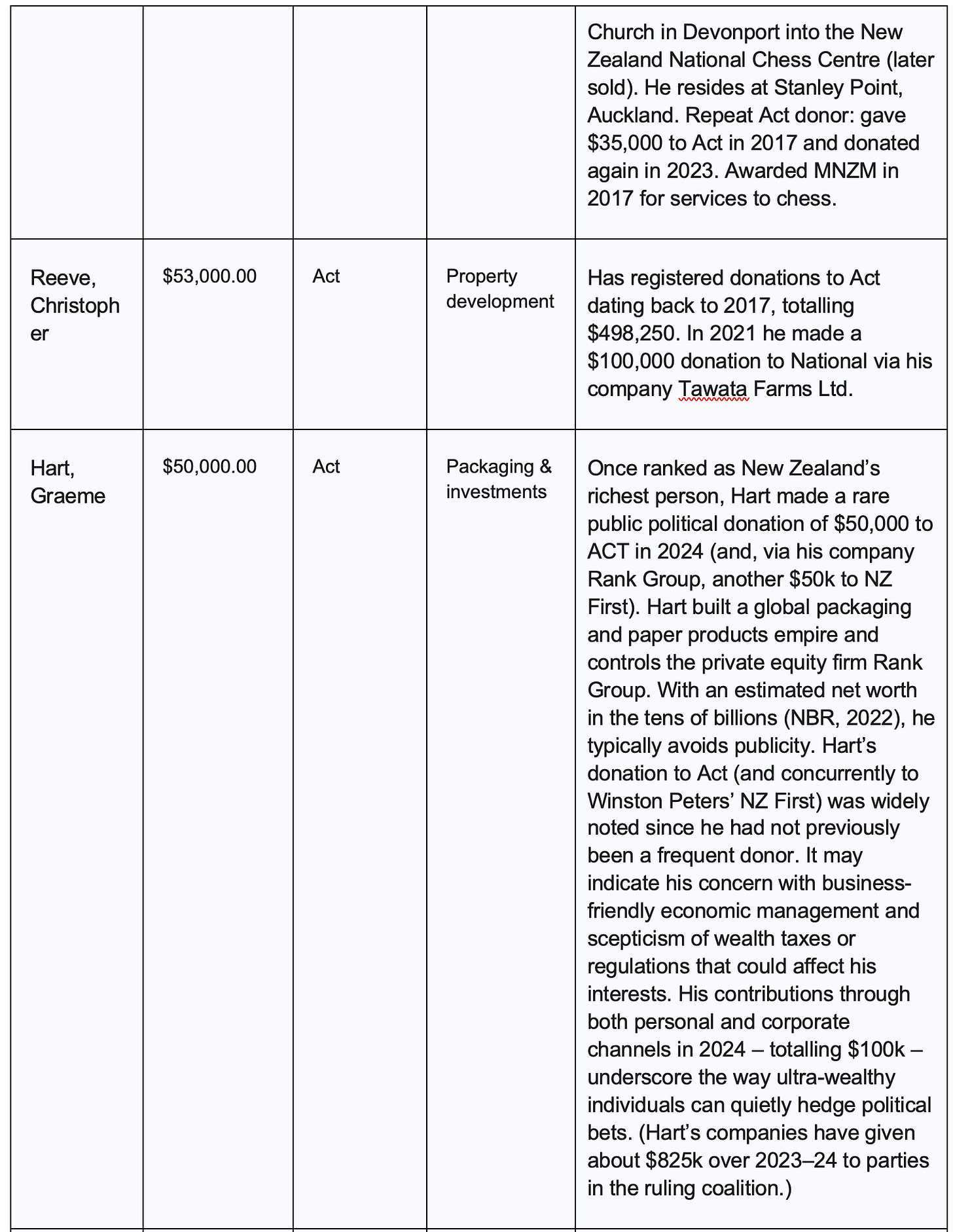

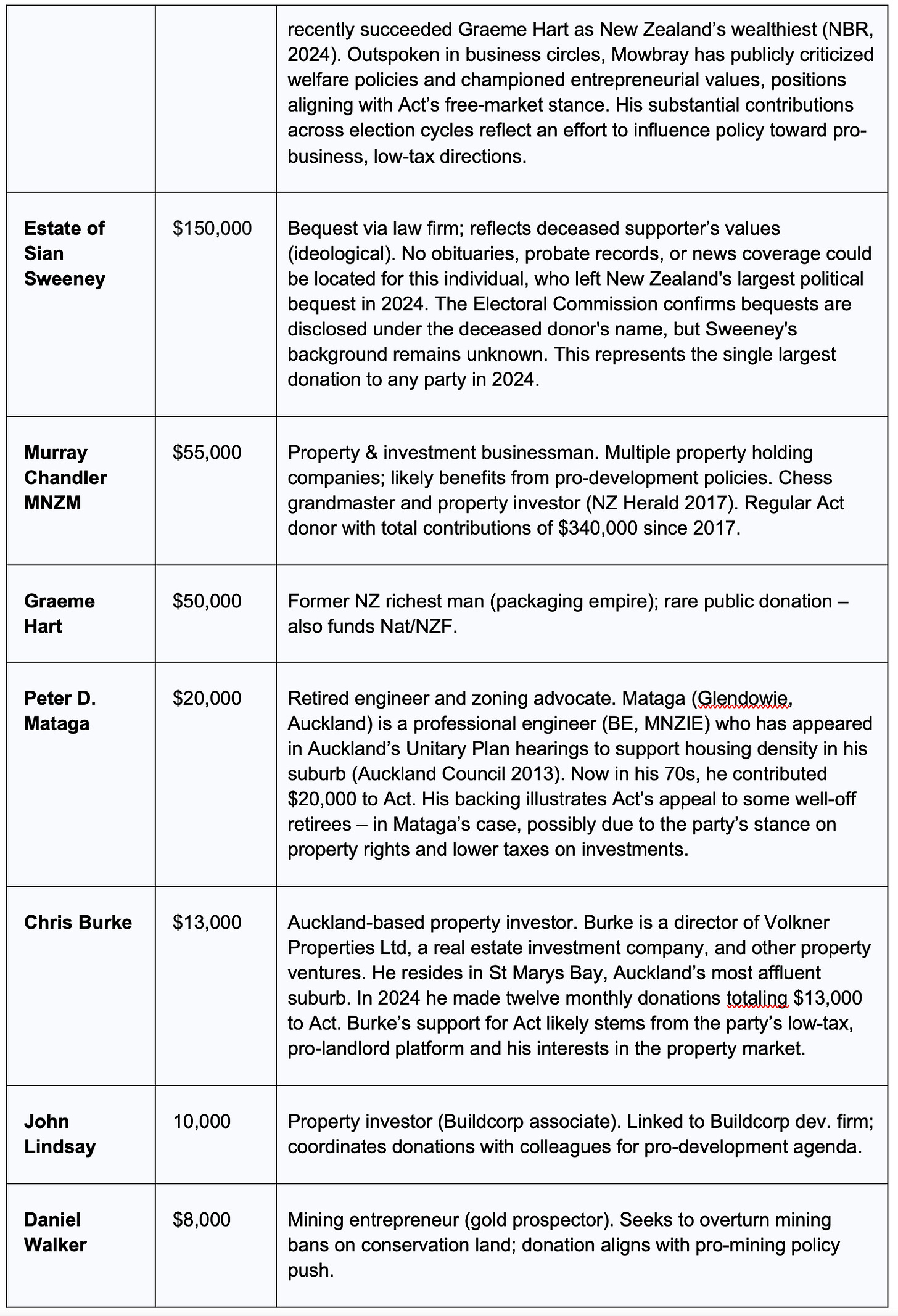

To understand the true nature of political finance in 2024, it is necessary to move beyond aggregate figures and examine the individuals and industries behind the largest donations. The data reveals not a random assortment of engaged citizens, but a highly concentrated and sectorally-aligned group of powerful interests. By classifying the donor data by industry, it becomes clear that specific parties are becoming heavily reliant on, and therefore potentially captured by, specific economic sectors. This analysis moves from how much was given, to who gave it and, most importantly, why.

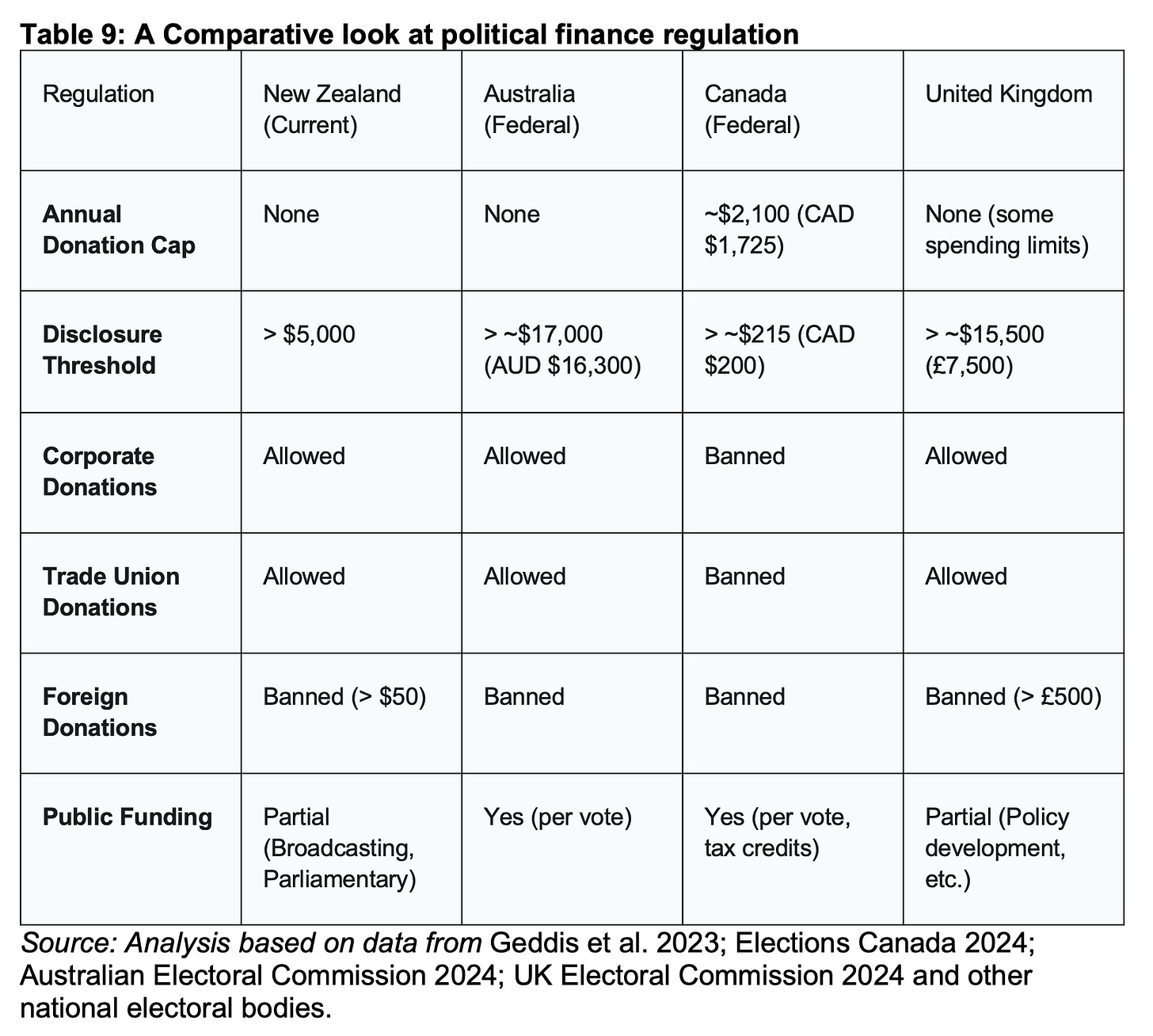

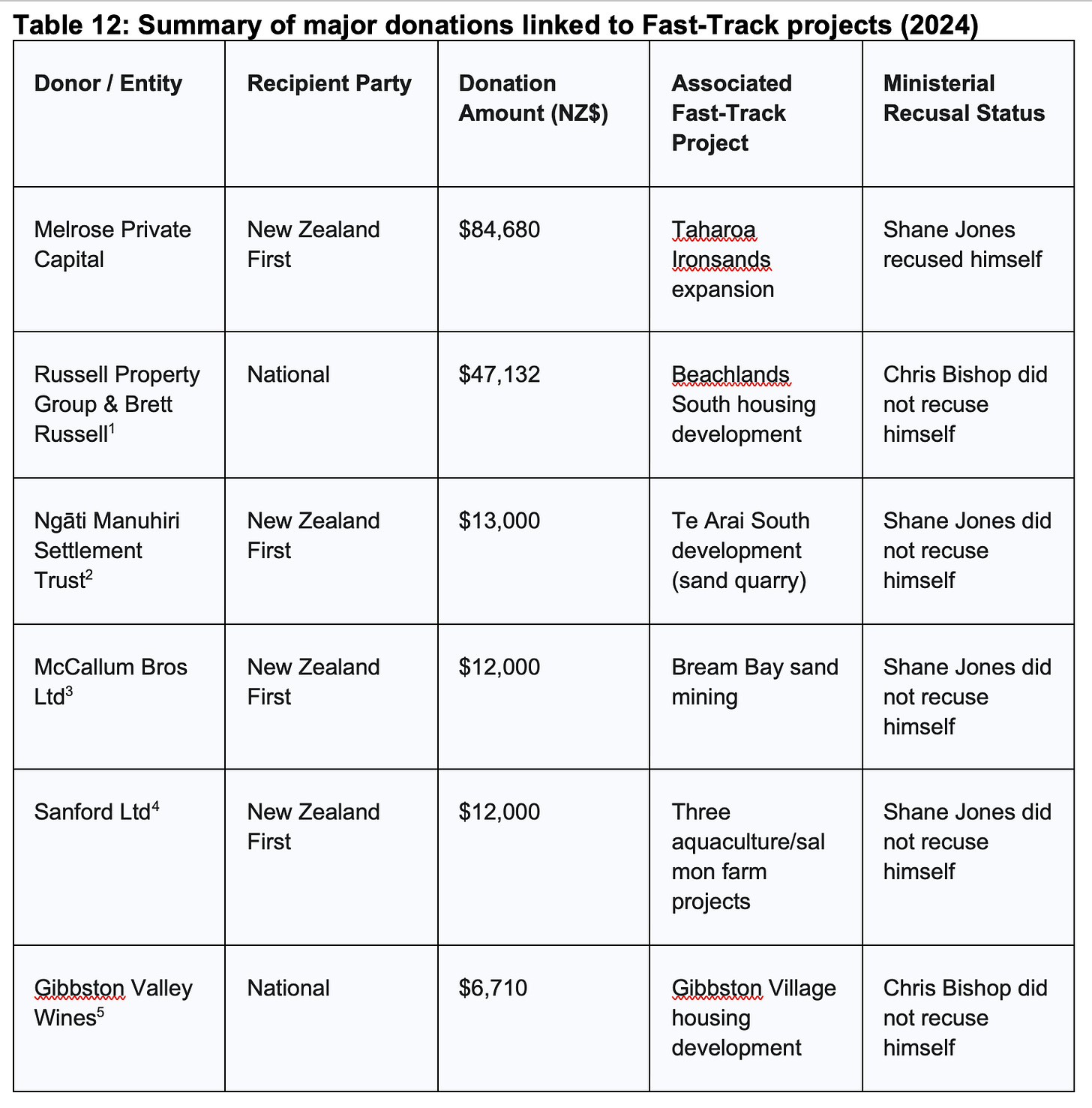

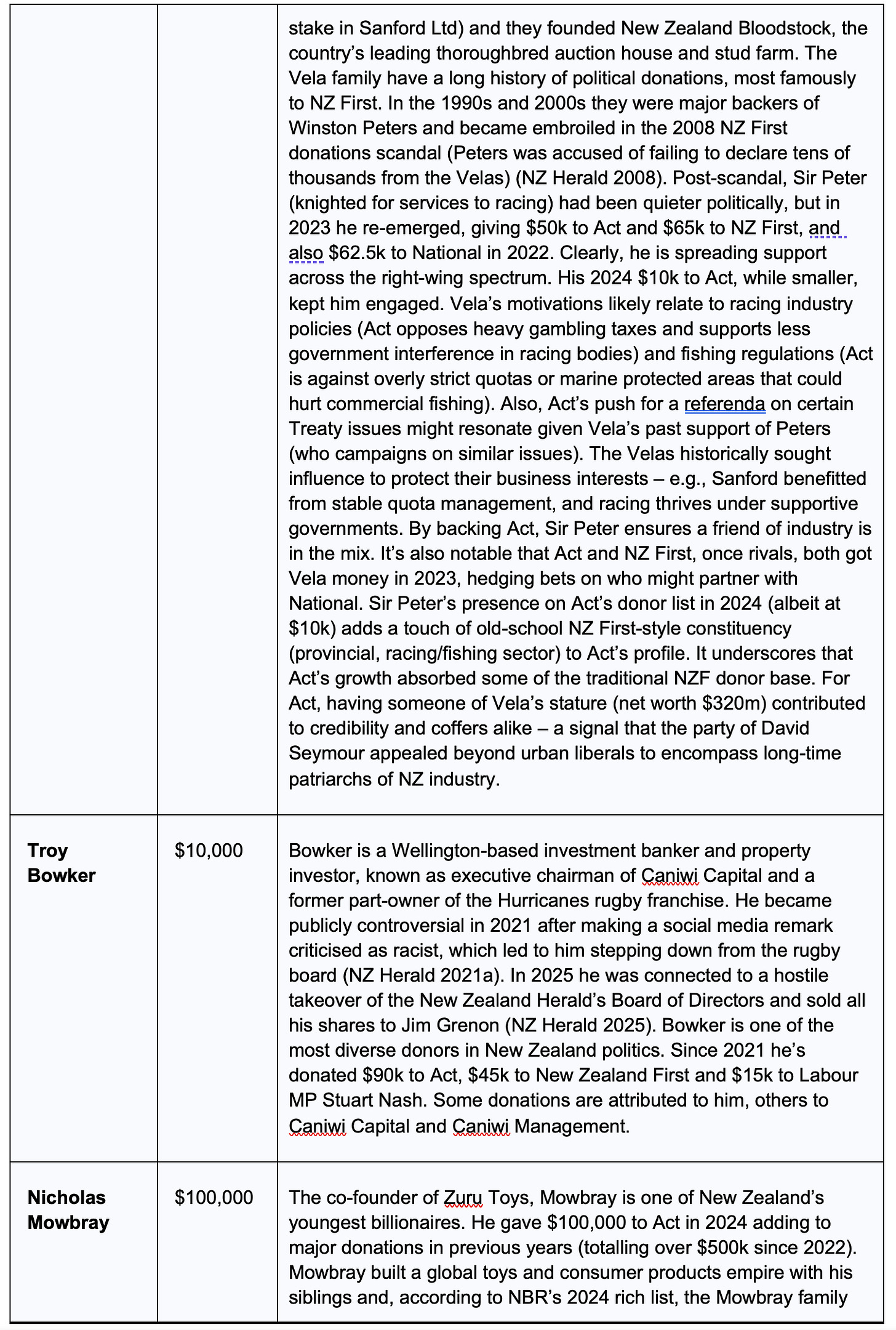

3.1 The $50,000+ club: New Zealand’s political kingmakers

At the apex of the donor pyramid is a small and exclusive group whose financial contributions grant them unparalleled influence. In 2024, twelve donors contributed $50,000 or more. Their combined donations totalled $1,289,178, representing roughly 11% of all money declared across all parties.

These are not average citizens participating in the democratic process; they are New Zealand’s political kingmakers, high-net-worth individuals and their corporate vehicles whose backing can sustain a political party’s campaign. Their shared characteristics — immense personal wealth and business interests sensitive to government regulation and taxation — provide a clear context for their political alignment.

For instance, packaging magnate Graeme Hart (net worth of about $12bn) donated $50k to Act and via his company gave another $50k to NZ First; and toy entrepreneur Nicholas Mowbray gave $100k to Act (NBR 2024; RNZ 2023a). Both have business empires that benefit from low-tax, low-regulation policies. These examples show how donors appear to openly align themselves with parties who have policies that align with their financial interests.

Table A, in the Appendix, provides some basic information about the twelve donors that contributed above $50k. This provides profiles of these top donors, including their backgrounds and political ties.

3.2 Building influence: The Property, construction, and infrastructure lobby

The single most powerful and organised donor bloc in New Zealand politics is the property and construction industry. An RNZ analysis found that since 2021, individuals and entities aligned with the property sector have donated more than $2.5 million, with 97% of that funding directed to National, Act, and NZ First (Palmer 2023). The 2024 returns show this trend continuing unabated.

This sector’s financial support is directly tied to its clear policy objectives: comprehensive reform of the Resource Management Act (RMA), the creation of fast-track consenting processes to bypass council regulation, and the maintenance of favourable tax settings, most notably the absence of a capital gains tax.

Major donors from this sector in 2024 include:

Real Estate Agencies: John Bayley of Bayleys Real Estate ($38,780 to National).

Property Developers: Christopher Reeve ($53,000 to Act), Brett Russell and his Russell Property Group (combined $47,132 to National), and the Mansons family via Mansons TCLM Ltd ($15,000 to National) are all major players in land and commercial development.

Opaque Development Interests: Donations also flow through less transparent entities, such as the three “Khyber Pass Companies” controlled by developer Yuntao Cai (combined $36,338 to National) and a group of companies located at Auckland’s Princes Wharf that are linked to property magnates the Chow Brothers ($10,000 to National).

Construction Companies: In 2024, National also received significant donations from major contractors like 3Eyes Construction ($23,650.65) and key suppliers to the industry, such as Manukau Quarries ($10,000) and heavy equipment manufacturer Transport Trailers Services Limited ($6,161.66). This demonstrates a broad-based financial alignment across the entire supply chain that stands to benefit from the government’s infrastructure and “red tape reduction” agenda.

Property is a heavily regulated sector (planning laws, infrastructure funding, etc.), so developers often court whichever party holds power. In 2024, National’s donor list was flush with real estate money.

Other notable National donors included the Brady family of South Auckland – who gave $20k split between their Ardmore quarry business and personal donations – and various developers or investors who stand to benefit from a pro-building, pro-RMA-reform agenda. For instance, Auckland investor Christopher Reeve (donated $53k to Act) owns property companies and would profit from looser resource consent rules and the absence of capital gains tax.

Likewise, Christchurch builder Stonewood Homes (Chow family) have appeared in donation lists, presumably anticipating influence on urban development policies.

The Goodfellow family (through ex-National president Peter Goodfellow, $10k in 2024) have extensive business holdings and longstanding ties, ensuring they’ll have an ear in policy circles. The pattern is clear: developers and construction firms donate to National/Act expecting a government that accelerates building projects, reduces compliance costs, and opens up land. While many frame their gifts as supporting a general ideology of growth, the direct business benefit cannot be ignored.

Fletcher Building defended its $7,200 donation to National (through Fletcher Concrete), saying it was simply paying for seats at a fundraising dinner (Thomas 2024). What is not acknowledged, however, is that in essence this is paying for privileged access to politicians. The risk is that such access translates into preferential input on policy (e.g. shaping reforms to zoning, infrastructure funding, or environmental rules to suit developers).

National and Act campaigned on repealing or loosening the Resource Management Act, which would clearly reward these donors. As one analysis bluntly noted, “donors like Reeve [a property investor] could directly profit if Act in government reforms property rules… a classic case of business funding its preferred policy outcomes”. This blurring of public policy and private interest is exactly what fuels conflict-of-interest accusations.

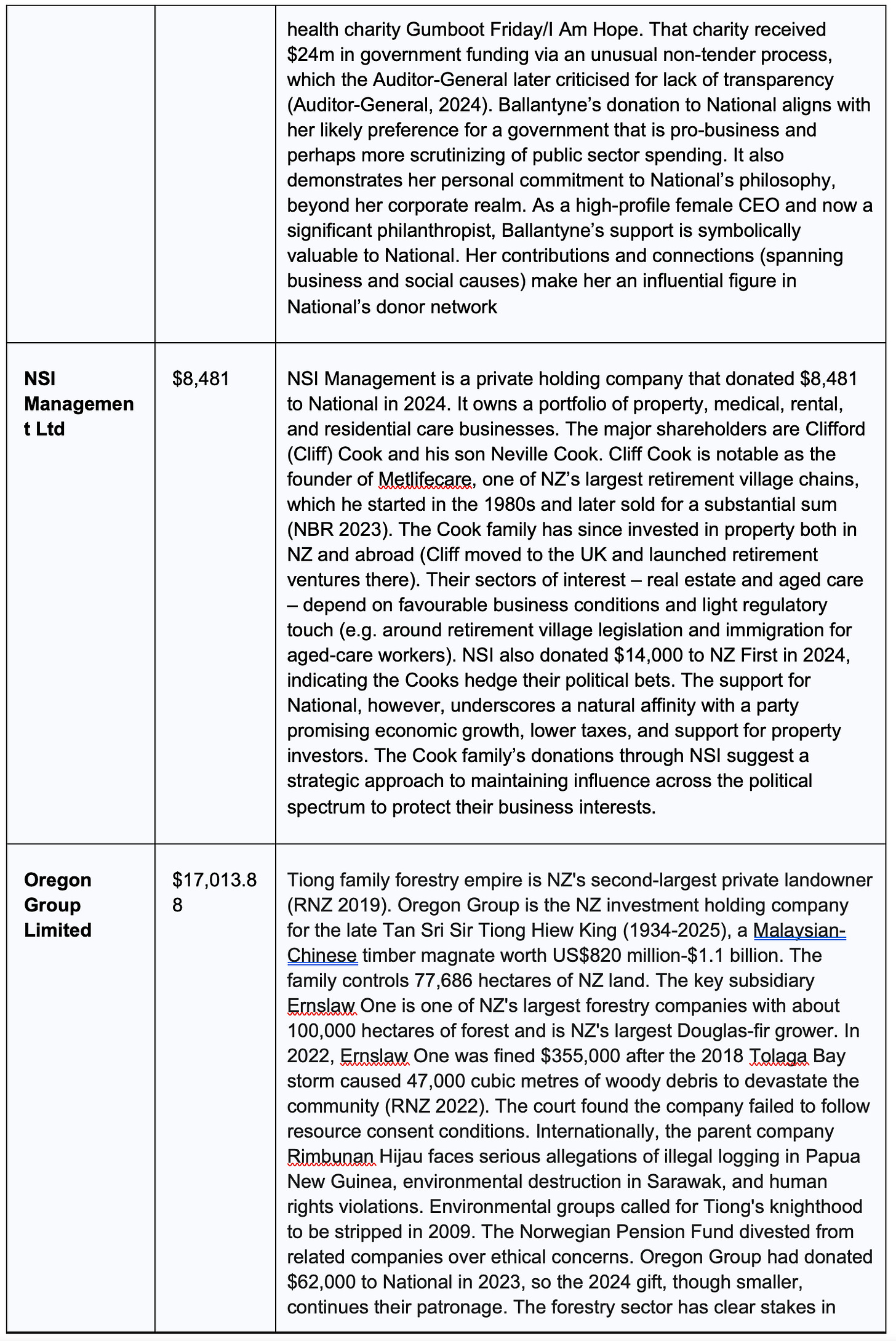

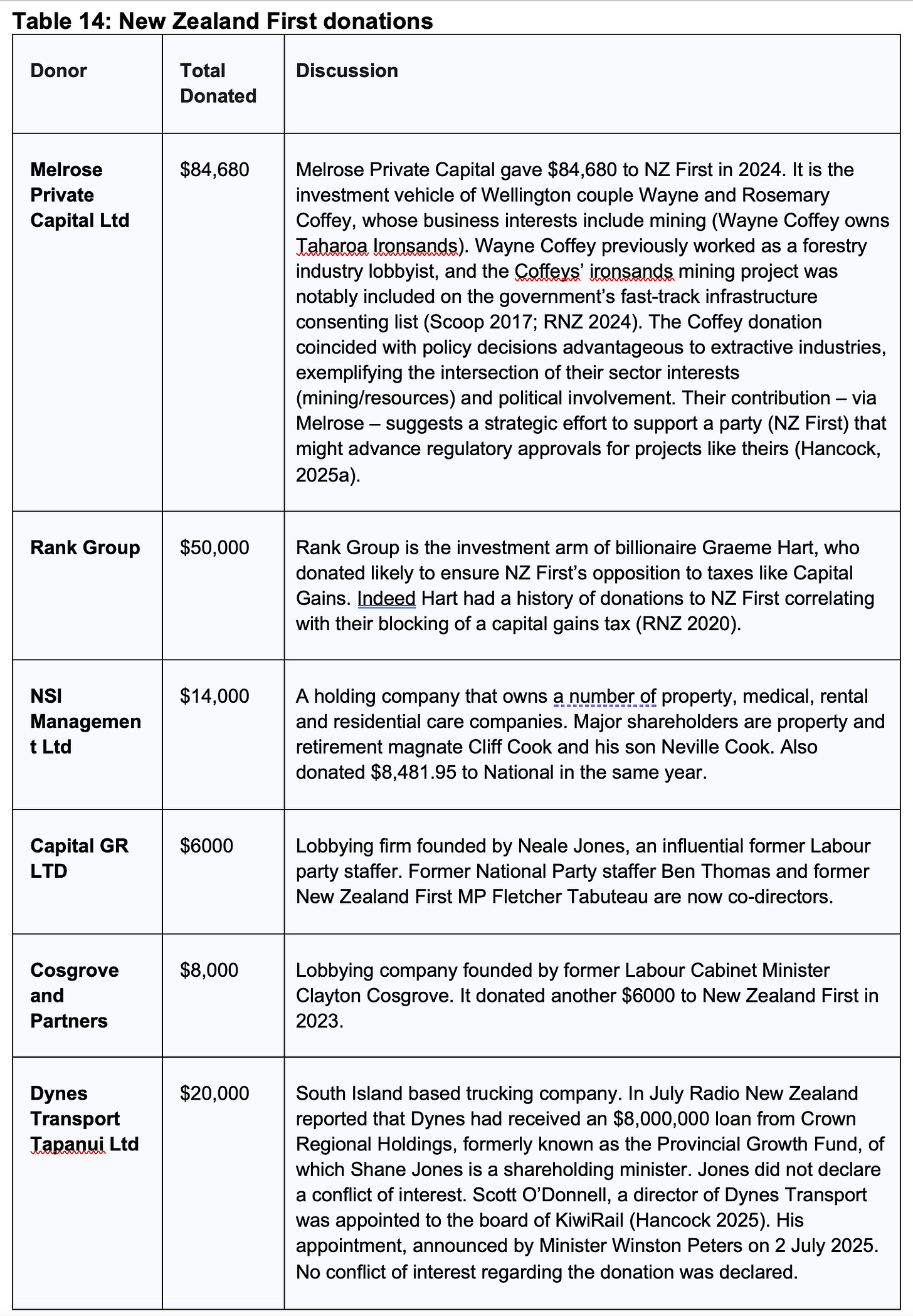

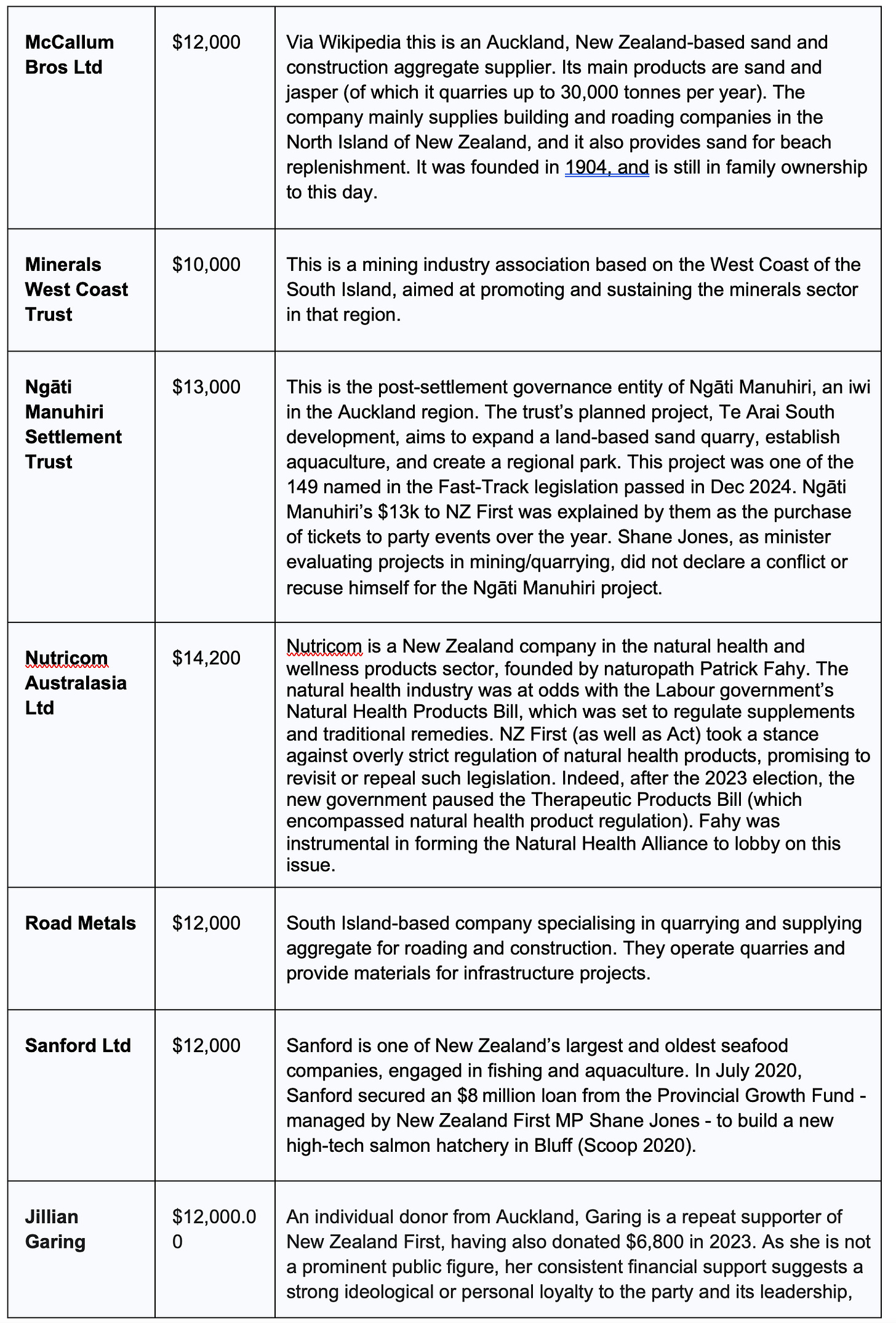

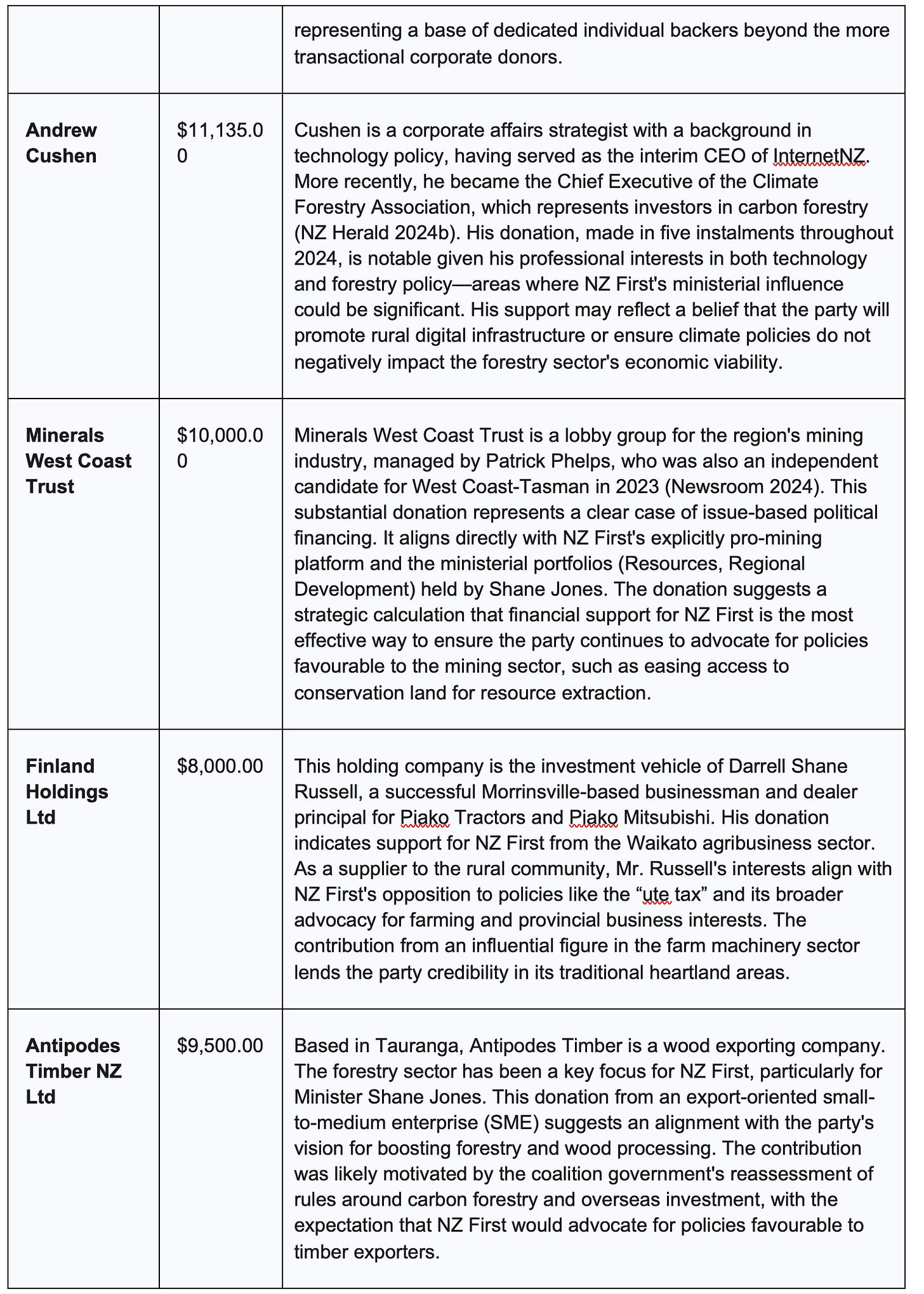

3.3 Digging for favour: The Extractive & primary industries

The second major donor bloc comprises companies and individuals from the mining, energy, quarrying, forestry, fishing, and agricultural sectors. These industries, which rely on access to natural resources and are heavily impacted by environmental regulations, have directed their financial support overwhelmingly to the coalition parties, particularly New Zealand First, which has built its modern brand on a pro-resource extraction platform.

Key donors in 2024 include:

Mining and Quarrying: Melrose Private Capital, an investment vehicle for the owner of Taharoa Ironsands, was NZ First’s largest donor ($84,680). Other donors include sand miners McCallum Bros ($12,000 to NZ First), the Minerals West Coast Trust ($10,000 to NZ First), aggregate supplier Road Metals ($12,000 to NZ First), and Patrick Phelps, a key lobbyist for mining ($10,000 to NZ First).

Energy and Forestry: The Todd Corporation, one of New Zealand’s largest energy conglomerates, donated to National ($5,468), while the Oregon Group, a major forestry owner, gave National $17,013.

Fisheries and Agribusiness: Seafood giant Sanford Ltd donated $12,000 to NZ First. Act received significant support from agribusiness figures, including kiwifruit industry leaders Craig and Shayne Greenlees ($20,000) and large-scale farmer Ron Frew ($15,000).

These contributions align with the coalition’s agenda of repealing environmental protections, promoting mining and oil exploration, and championing provincial industries against what they term excessive “red tape.”

Several extractive industry players backed the coalition parties last year, in some cases outside of the fast-track context. NZ First received donations from the coal, oil, and minerals camp in line with its resources-focused agenda. For example, Bathurst Resources (a coal mining firm) donated to NZ First (exact amount was below disclosure threshold, but known from media) and had met with party officials regarding coal policy.

The Dynes family’s transport company (Dynes Transport, which hauls coal and forestry products) gave $20,000 to NZ First, reflecting confidence that NZ First would push for regional roading and resist tough emissions regulations on trucking. Indeed, such donors likely welcomed NZ First’s scepticism of strict climate measures and promotion of provincial industries.

On the National/Act side, oil exploration interests and climate policy opponents have also been active donors: reports indicate Mark Dunphy, a petroleum investor who advocated to restart offshore drilling, contributed to right-leaning campaigns (though not publicly disclosed in 2024, he was active in 2023).

The “National Green Steel” project proponents (the Garg family) donated to National in 2023 – a small amount ($5k) but symbolically important given their project to create a hydrogen steel plant relies on favourable government support. All these contributions underscore how natural resource companies invest in parties that will favour development over environmental restraints.

The conflict concern is that ministers may feel beholden to these donors when setting policy on mining permits, environmental standards, or climate action. Notably, Shane Jones even added sand and aggregates to a “critical minerals” list, easing rules for quarries – a direct nod to donors like McCallum and J Swap (Tibshraeny 2024; MBIE 2024).

Beyond Sanford’s fisheries donation noted earlier, other primary-sector businesses made targeted contributions. Mining, forestry and agriculture interests, for instance, quietly back NZ First and National. [In 2024 NZ First received funds from sources like Phelps & Co. (West Coast) – a forestry/logging family business (media noted a donation from [Brian Phelps], $10k, tied to NZ First’s pro-forestry stance).]

The Antipodes Aqua salmon farm (Marlborough) proponents were also linked to donations. Meanwhile, Act attracted support from wealthy farmers and agribusiness figures frustrated with environmental regulations: e.g. the Van Den Brink family (poultry farming empire) has been known to support Act’s anti-regulation platform (though specific 2024 amounts were below disclosure).

Rod Drury (tech entrepreneur) is another example: while his $100k to Act in 2022 was supportive of a party he backed, he publicly noted an “expectation that once you’re successful, you contribute to the political system” (Newshub 2022). Drury isn’t seeking government contracts, but his comment reflects how business leaders feel obliged to donate. In the primary sector’s case, donations often aim to stave off unwelcome regulation – e.g. fishing companies, trucking firms, farming co-ops all give to parties that promise to “get government out of the way.”

The conflict arises if those parties, once in power, water down regulations or enforcement in ways that specifically benefit their donors (for example, relaxing catch limits after a fishing company’s donation, or delaying emissions fees for trucking after transport operators fund the campaign). While such policy decisions can be defended on ideological grounds, the perception of payback is hard to avoid when the money trail is public.

3.4 Paying for a seat at the table: The Professional influencers

Perhaps the most explicit form of “cash for access” comes from donations made directly by professional lobbying firms and industry associations. For these entities, political donations are not a form of civic participation or philanthropic support; they are a strategic business expense, designed to build relationships, secure meetings, and ensure their clients’ interests are heard by decision-makers.

In 2024, several corporate lobbyists made declared donations:

Capital Government Relations Ltd: A prominent lobbying firm with directors from across the political spectrum, including a former NZ First MP, donated $6,000 to New Zealand First.

Cosgrove and Partners: A firm founded by a former Labour Cabinet Minister, donated $8,000 to New Zealand First.

Thompson Lewis: A public relations firm founded by a former Chief Press Secretary to Helen Clark, donated $6,000 to the Labour Party.

Massey Coates: Nicholas Albrecht is the director of corporate lobbying consultancy firm Massey Coates, and he donated $9,038.99 to National. Albrecht was previously Vector’s in-house lobbyist for 14 years (2008-2022)

Spirits New Zealand: The industry lobby group for the liquor industry donated $6,114 to National.

Orange PR Media Limited: Donated $8,732 to National. Orange PR is a marketing and event agency with offices in Auckland and Fujian, China.

These donations blur the line between democratic engagement and commercial transaction, creating a tiered system of access where those who can afford to pay a lobbying firm — and have that firm make donations on top of its fees — are granted a privileged hearing.

While these sums are modest – and possibly represent the price of access to party fundraising events with politicians – they raise eyebrows: lobbyists typically seek access through meetings and advocacy, so their direct financial contributions to a party blur the line between professional lobbying and political patronage. It could be seen as lobbyists paying to sustain relationships or goodwill with a party that ended up in government. Essentially, those who already hold influence (via connections) are also contributing money, amplifying their clout.

This trend of lobbyists donating cash underscores the report’s theme that access is increasingly monetised. Not only do businesses donate for favourable policy, but influence brokers themselves are entering the fray financially.

Construction and infrastructure contractors often rely on government spending (roading, public works), which is a dynamic that can turn donations into potential conflicts. A clear case is Road Metals Co, a Canterbury gravel and machinery supplier who donated $12,000 to NZ First. As a regular contractor for highway projects, Road Metals would benefit from NZ First’s push for big regional infrastructure builds. Its donation signals a bet that NZ First ministers will channel funding to roads and quarries or oppose policies that raise costs for heavy industry.

Similarly, engineers and lobbyists connected to transport have shown up in National’s donor rolls (e.g. names linked to roading consultancies giving in the $5k–10k range). Each such gift is relatively small, but collectively they ensure their interests are heard in the halls of power.

Section 4: Case studies in quid pro quo: How money translates into access and outcomes

The patterns of sectoral giving provide the context, but the most compelling evidence of a political system under strain emerges from specific case studies where a direct line can be drawn between a financial contribution and a favourable government action. The following cases from 2024 and 2025 demonstrate how money translates into tangible outcomes, from fast-tracked project approvals to board appointments and national honours.

Across these examples, a common theme emerges: the defence that “no rules were broken” is consistently used to justify outcomes that fail the basic test of public confidence. This gap between technical legality and perceived integrity is where public trust is lost.

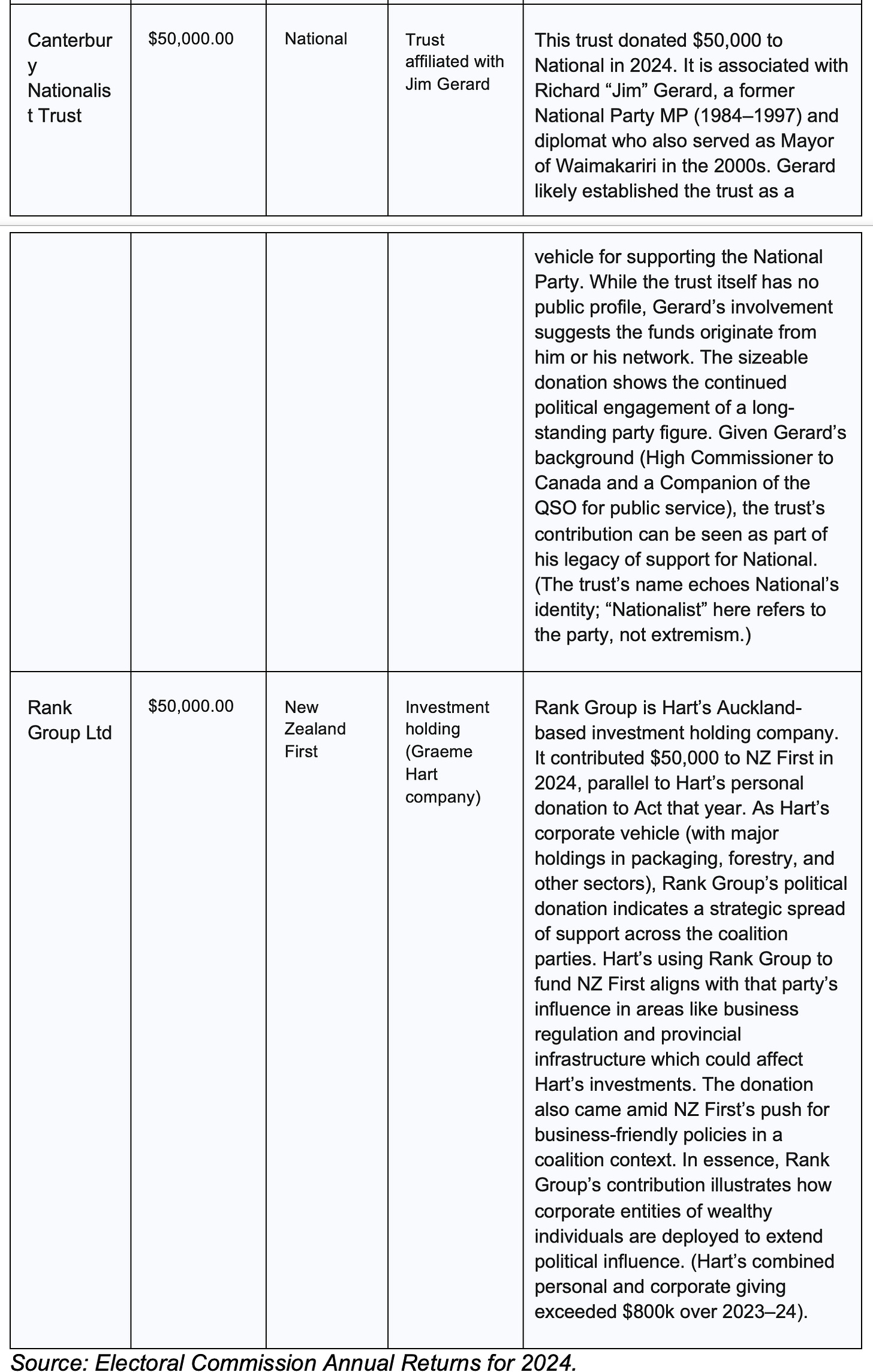

4.1 Case Study: A “Pay-to-Play” system? The Fast-Track Approvals Act

In December 2024, the coalition government passed the Fast-track Approvals Act, a key part of its coalition agreement. The Act creates a “one-stop-shop” for projects of national or regional significance, allowing them to bypass normal consenting processes under the RMA and other environmental legislation. [Crucially, a panel of ministers — including those for Infrastructure, Transport, and Regional Development — holds the power to refer projects into this streamlined process.]

An analysis of the 2024 donation returns reveals a disturbing pattern: a significant number of companies and individuals who successfully had their projects included on the fast-track list were also major donors to the political parties whose ministers were making the decisions. In total, donors linked to fast-tracked projects gave approximately $121,680 to New Zealand First and $58,897 to National during 2024 (Hancock 2025a). This continues a pattern identified by RNZ in late 2024, which found over $500,000 had been donated by entities linked to fast-track projects in the preceding years (Hancock 2024).

National and NZ First attracted donations from several businesspeople whose projects benefited from fast-track approvals. One striking case: developer Brett Russell donated $35k to National just 10 days after his large housing project (Beachlands South) was accepted into the fast-track programme (Hancock 2025a). Naturally, the public might speculate whether the donation was coincidental to the decision, made in appreciation of the decision, or even an expected contingent reciprocation.

Similarly, McCallum Bros, who made a $12,000 donation to NZ First, received fast-track approval for 8 million cubic meter sand mining from Bream Bay despite significant opposition from local Māori. The company has 120+ years of operations but made its first-ever political donation to NZ First in 2024, coinciding with seeking fast-track approval for their most controversial project. See Table B in the Appendix, for a full list of donations from successful fast-track projects.

The defence from the ministers involved is that donations to a political party do not constitute a personal conflict of interest. However, this position was tested by the Auditor-General in a June 2025 review of the fast-track process (Office of the Auditor-General 2025).

While the Auditor-General found the formal system for managing conflicts was “sound,” the report issued a significant warning about the gap between rules and public perception. The report stated: “Further thought could be given to the risks associated with making decisions that tangibly benefit a party donor and how these are perceived... This could include considering whether the Cabinet Manual should provide more guidance about political donations and conflicts of interest” (Office of the Auditor-General 2025).

This nuanced finding, far from an exoneration, validates the core concern: the current rules are insufficient to manage the perception of quid pro quo, which can be as damaging to public trust as overt corruption.

The issue of fast-track donations will become more problematic in the 2026 election year: the Minister of Infrastructure (who is also oversees the fast-track approvals) is Chris Bishop, and he’s also the Chair of the National Party’s election campaign committee. As Chair he will have all the information about donations to the campaign. The fact that he will be in full knowledge of who is donating, while also acting as the gate keeper to the fast-track processes will become a bigger conflict of interest.

4.2 Case study: A “Perfect storm” of influence: The Dynes-KiwiRail affair

No single case in 2024 better illustrates the multi-faceted confluence of money, policy, and appointments than the relationship between Dynes Transport, the New Zealand First party, and the state-owned rail operator, KiwiRail. In an RNZ article on this affair, I was quoted describing the sequence of events as a “perfect storm” that erodes public trust in the political system (Hancock 2025a).

The timeline is stark:

1. The Loan: In May 2025, a joint venture involving Dynes Transport, the Southern Link Logistics Park, received an $8 million regional infrastructure loan from Crown Regional Holdings (Hancock 2025a). This entity is the successor to the Provincial Growth Fund, and New Zealand First MP Shane Jones is a shareholding minister. Jones defended the decision, stating that five ministers were involved and that party donations were not considered a conflict of interest.

2. The Appointment: On 2 July 2025, New Zealand First leader and Minister for Rail, Winston Peters, announced the appointment of Scott O’Donnell, a director of Dynes Transport and executive director of the H.W. Richardson Group, to the board of KiwiRail (Peters 2025).

3. The Donation: On 18 July 2024, Dynes Transport Tapanui, a major South Island trucking company, donated $20,000 to the New Zealand First party.

This case demonstrates a trifecta of influence: a party donation is followed by a favourable ministerial funding decision and a high-profile board appointment, all involving the same company and the same political party.

The Conflict of interest problem

The O’Donnell appointment was problematic from the outset, and has become increasingly so. O’Donnell is a director of Dynes Transport Tapanui and an executive director of the H.W. Richardson Group (HWR), one of New Zealand’s largest privately-owned transport conglomerates, which owns 46 companies and employs around 2,000 people (Hancock 2025b). Many of these companies operate in sectors that directly compete with or supply services to KiwiRail.

Documents released under the Official Information Act reveal that even KiwiRail’s newly-appointed chair, Sue Tindal, expressed unease about O’Donnell’s appointment before it was confirmed. In correspondence with Treasury officials, Tindal questioned the extent of O’Donnell’s business interests and suggested they could prove a test of his loyalties. As one email between Treasury officials summarised: “Her initial impression is that Scott has financial and beneficial interests in HWR which would significantly conflict with KiwiRail... There are also questions around where his loyalties would lie in many different types of decisions that would overlap between HWR and KiwiRail” (Hancock 2025b).

Notably, O’Donnell initially provided Treasury with a list of only four companies where conflicts might exist. However, Tindal checked publicly available information in the Companies Office register and hand-drew an “interests diagram” that identified 11 companies with potential conflicts – nearly three times what O’Donnell had disclosed (Hancock 2025b). The final conflict of interest management plan covers 10 companies.

To manage these extensive conflicts, Treasury responded with a seven-part conflict-management regime involving information barriers, agenda vetting, mandatory declarations, recusals, board-directed exclusions, and ongoing reporting to shareholding ministers (Hancock 2025b).

Impacts on board efficiency

The consequences of this elaborate conflict management regime became apparent in December 2025, when Chair Tindal was questioned during a parliamentary scrutiny week hearing. Asked by Act’s Simon Court whether the conflict management arrangements had impacted the board’s capability and efficiency, Tindal confirmed: “It does have an effect is the answer to that” (James 2025).

Tindal revealed that O’Donnell had already been required to recuse himself from “a number of items on the board agenda”, and added that regular reporting to shareholding ministers – due in early 2026 – would make “quite evident” the extent of time that director has to be recused. More pointedly, she noted that O’Donnell “needed to consider whether [he] can discharge [his] duties as required in accordance with the Companies Act” – a remarkable statement that raises fundamental questions about whether the appointment should have proceeded at all (James 2025).

When approached by RNZ, KiwiRail declined to disclose how many board meeting agenda items O’Donnell had missed due to his conflicts, stating that this information was being compiled for the reporting to shareholding ministers (James 2025).

A “Mickey Mouse” arrangement

While Treasury’s conflict management plan may satisfy the formal requirements of public sector governance, it is substantively inadequate. In response to the original RNZ reporting, I described the situation as a “Mickey Mouse” arrangement, noting: “It’s incredible. There are lots of logistical experts that are well-qualified to be appointed to the KiwiRail board. It’s bizarre that they’ve gone with one that is also a competitor to KiwiRail” (Hancock 2025b).

The core problem is that Minister Peters’ geographical recusal plan, whereby O’Donnell recuses himself from KiwiRail activities “primarily south of Oamaru” (Peters 2025), fails to address the strategic, national-level conflicts at the heart of KiwiRail’s operations. Critical decisions affecting rail freight, track access pricing, capital allocation, and KiwiRail’s relationship with major transport competitors are made at the board level in Wellington. A regional recusal is a cosmetic fix for a pervasive conflict.

While the Cabinet Manual allows for mitigation in some circumstances, it is clear that where a conflict is “significant and pervasive”, the appropriate remedies are divestment of the interest or resignation from the conflicting position. Yet in this case, O’Donnell was permitted to remain a director of Dynes Transport and H.W. Richardson Group while joining the KiwiRail board, creating an ongoing situation of dual fiduciary duty that cannot be adequately managed through procedural measures.

Systemic concerns

The Dynes-KiwiRail affair is, at its heart, a case study in the intersection of three systemic integrity issues: the influence of political donations on government decision-making; the inadequacy of current conflict of interest management regimes; and the risks of political patronage in public sector appointments.

The entire sequence creates an unavoidable perception that the $20,000 donation bought privileged access and favourable consideration across multiple government portfolios controlled by New Zealand First. This perception is precisely what the Auditor-General warned about in his June 2025 report on the Fast Track Approvals process, where he noted that ‘further thought could be given to the risks associated with making decisions that tangibly benefit a party donor’ (OAG 2025).

This case highlights the urgent need for reform: cooling-off periods between donations and eligibility for government funding or appointments; clearer Cabinet Manual guidance on party donations as potential conflicts; and more rigorous vetting of appointees’ commercial interests before, not after, appointments are announced.

It should also be noted that the $20,000 Dynes donation to NZ First is part of a wider pattern of support from the transport and primary industries sector, which also includes other 2024 donors such as Road Metals ($12,000) and Finland Holdings ($8,000).

4.3 Case study: Cash for honours? – Devaluing New Zealand’s highest accolades

The perception that New Zealand’s highest national honours can be bought is not new. In a 2014 speech in Parliament, then-opposition MP Chris Hipkins listed several prominent National Party donors who had received knighthoods or other honours, directly accusing the government of a “cash-for-honours” system:

“Look, for example, at the number of National Party donors who have been given honours under this Government. Tony Astle — 60 grand to the National Party was enough to make him an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit. Chris Parkin gave $66,000 to the National Party, and that made him a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit. Sir Graeme Douglas — twenty-five grand gave him an insignia of the Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit. Sir William Gallagher — $42,000 got him a knighthood. Lady Diana Isaac — $20,000 made her an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit. [Interruption] Oh, there is old “Maestro”, Jonathan Coleman, piping up at the perfect time, of course, because we know that Garth Barfoot gave him $5,000 for his campaign and he got made a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit in exchange for that.” (Hansard 2014)

The events of 2025 suggest this issue remains a bipartisan concern. The close proximity of very large political donations to the receipt of knighthoods has once again brought the integrity of the honours process into question.

In 2025 these are the two donors who were knighted:

Sir Brendan Lindsay: The founder of Sistema Plastics, Sir Brendan donated a total of $453,392 to the three coalition parties (National, Act, and NZ First) across 2022, 2023 and 2024 (including a 2024 donation to National of $138,392.78). He does not appear to have made any declarable political donations prior to 2023. In the June 2025 King’s Birthday Honours, he was made a Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for “services to business and philanthropy”. No media coverage of his knighthood mentioned his political giving.

Sir Ted Manson: A major Auckland property developer, Sir Ted’s family firm (Mansons TCLM) donated $15,000 to National in 2024, following a $70,000 donation from his son in 2023. Also, on September 26, 2024, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon’s official diary records a meeting described as “COFFEE: Ted Manson”. Then in the 2025 New Year’s Honours, Ted Manson was made a Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for “services to business, philanthropy, and the community”. The sequence of a large donation and a personal meeting with the Prime Minister, followed by a prestigious national honour, creates an undeniable perception that the honour was linked to the financial support and the access it granted.

Richard Balcombe-Langridge MNZM donated $10,277.80 to the National Party in 2024, and received a King’s Birthday Honour for services to business in 2025.

This pattern mirrors the United Kingdom’s infamous “Cash-for-Honours” scandal, where large, undeclared loans to the Labour party were linked to nominations for peerages (BBC News 2007). In that case, while no criminal charges were ultimately laid, the scandal did immense damage to public trust and the credibility of the honours system.

The issue is not whether the recipients are worthy philanthropists, but whether the system is perceived to be one where a very large donation is a prerequisite for consideration. This perception devalues the honour for all recipients and corrodes the principle of merit-based public recognition.

Lindsay and Manson aren’t the only donors on the list who have received honours – they are only the latest to be made knights. Longtime National donor Sir Graeme Harrison (of ANZCO Foods) gave over $100k in recent years and sits on the National Party’s board, exemplifying how major donors often receive establishment recognition. Labour also received $20k from retired food-industry entrepreneur Dick Hubbard ONZM. And Act received $10,000 from Sir Peter Vela and $21k from Dame Jenny Gibbs (bringing her total donations to Act to $741,989 to Act since 2014). See Appendix 2 for more on all these donors. More research on the relationship between royal honours and donations is required.

4.4 Case study: Regulatory U-turns in natural health

Beyond fast-track projects, donors have successfully opposed unwanted government regulation. A salient example is the natural health products lobby. Nutricom Australasia (a supplements company whose owner was a key figure in the Natural Health Alliance) donated $14,200 to NZ First in 2024. The party then campaigned against the Therapeutic Products Act 2023 – a law that would tightly regulate natural health products.

After the election, NZ First negotiated to include the repeal of the Act in their coalition agreement with the National Party. Shortly after coming to power the Government repealed the Act and by December 2024 had had entirely revoked the Therapeutic Products regime (National–NZ First Coalition Agreement 2023; New Zealand Parliament 2024). This pleased the supplements industry which considered the law overreaching.

Internal government briefings confirm NZ First Associate Health Minister Casey Costello met with Natural Health Alliance representatives (including Nutricom’s owner) early in 2024 to discuss scrapping the “overregulated” system (RNZ 2024). This is a textbook case where a donor’s desired policy outcome (no stringent regulation on their products) was achieved soon after their contribution – a coincidence that can’t be ignored.

4.5 Case study: Carbon farming, the ETS, and climate policy

One of the most conspicuous examples of donor interests intersecting with government policy comes from the burgeoning carbon farming industry. In 2024, a cluster of donations tied to a single carbon credit company demonstrated how “green” business interests seek to shape climate policy. The donor in question, NZ Carbon Farming (via entities linked to its director Matthew Walsh), made substantial contributions to the National Party.

This occurred just as the incoming government was gearing up to review New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) – a move with huge financial stakes for anyone in the carbon credit game. The confluence of timing, money, and policy here suggests a sophisticated attempt to influence the rules of the carbon market through political donations. This case study shows that it’s not only traditional industries like property or transport looking for political favour – even players in the climate change economy now use their financial resources to ensure their interests are heard.

Key Donor: A coordinated cluster of companies controlled by Matthew Walsh – principally NZ Carbon Farming Ltd and two associated firms (Tonic 42 Ltd and Mjtk Ltd) – donated a combined $52,482 to the National Party in 2024. These three donations, each below $25k but together exceeding $50k, were all lodged via the same accountancy firm’s address, indicating a deliberate, structured giving strategy.

NZ Carbon Farming is one of New Zealand’s largest carbon offset companies, specialising in planting forests (often pinus radiata) to earn carbon credits under the ETS. By splitting the contribution across multiple entities, the scale of his contribution is less easy to identify, and also signalled that this was a business-backed effort, with a professional veneer (using an accountancy hub) rather than a single individual’s whim.

Vested Interest: NZ Carbon Farming’s entire business model is predicated on ETS settings and climate regulation. The company’s profitability depends on the market price of carbon credits and the rules around what kind of forestry qualifies for credits. At the time of the donation, the new National-led government had announced a major review of the ETS and was expressing scepticism toward policies perceived as punitive on industry.

A key debate in climate policy was whether to restrict exotic tree plantations in favour of native forests for carbon offsets – a policy shift that would directly impact NZ Carbon Farming’s operations. The company thus had a multi-million dollar stake in how the government might tweak carbon credit rules, international carbon trading, and related climate measures. By funding National, NZ Carbon Farming and its associates were effectively investing in influence: ensuring they have the ear of policymakers as these critical decisions are made.

Policy Link/Outcome: The donations from Walsh’s cluster can be read as a strategic down payment on favourable policy. In government, National and its coalition partners indeed took a markedly industry-friendly approach to climate issues. They ordered an ETS review, signalled a pause or dilution of some climate regulations, and framed climate policy in terms of “pragmatism” and economic balance – positions very much aligned with large-scale carbon offset sellers who prefer flexible, high-volume credit markets.

While it’s impossible to draw a direct line from NZ Carbon Farming’s $52k to any single decision, the alignment of interests is undeniable. The company gained access and goodwill with the ruling party, and in turn the government’s early moves (such as reconsidering the ban on exotic forests in the ETS, and slowing the rise of carbon prices) benefited big carbon credit owners.

This case illustrates a modern form of green lobbying: far from being anti-environmental, a donor can be deeply involved in the climate economy yet still seek to influence rules for profit. It underscores that even climate policy – an area one might hope is driven solely by science and the public good – is subject to the same political finance pressures as any other big-money sector.

4.6 Case study: The Construction ecosystem and the infrastructure agenda

The influence of money in politics often extends beyond obvious players to an entire ecosystem of aligned interests. Nowhere is this more evident than in the construction and infrastructure domain under the National-led Government in 2024–25. Previous case studies highlighted property developers as key donors, but a closer look reveals that donations flowed from every part of the construction supply chain.

Major contractors, materials suppliers, and industrial manufacturers opened their wallets for the political parties championing a big infrastructure build-out. These contributions were essentially sector-wide bets on a friendly government: National’s campaign promises of new highways, streamlined consents, and public works meant a potential boom for everyone in the building business. This case study shows how a whole industry network can mobilise financially to tilt the policy environment in its favour, and how that investment can pay off through government agendas that cater to their economic interests.

Key Donors from the Construction Supply Chain: In addition to donations from property developers, National’s 2024 return featured significant contributions from:

· Major construction contractors – e.g. 3EYES Construction Ltd gave $23,650. 3EYES is a large Auckland-based builder involved in commercial and high-end residential projects (including notable hotel and resort developments). Its donation brought a frontline contractor into National’s donor cadre, not just the property owners.

· Core materials and logistics suppliers – e.g. Manukau Quarries LP donated $10,000. This company supplies the aggregate and raw materials fundamental to roading and construction, indicating the quarrying sector’s stake in National’s infrastructure push. (Tellingly, Manukau Quarries’ owners made an identical personal donation on the same day, doubling their support and hinting at an orchestrated effort.) Another example is Transport Trailers Ltd, a manufacturer of heavy transport equipment, which donated about $6,160. Such firms usually stay out of politics, so their donations signal that they clearly anticipated big growth under a National government’s building spree.

Vested Interest: All these contributors share a direct financial interest in a pro-construction policy environment. National campaigned on an expansive infrastructure agenda – including new highways (the “Roads of National Significance”), rapid transit projects, and loosening of Resource Management Act constraints on development.

For construction contractors like 3EYES, this means more government contracts to bid on and a steady pipeline of projects. For quarries and materials suppliers, more roads and buildings mean higher demand for gravel, cement, steel, and other inputs. For equipment makers and trucking firms, it means more machinery to sell or lease and more goods to haul. In short, every link in the construction chain stood to benefit financially from National’s policy platform of “building back” infrastructure.

Their donations can thus be seen as a collective stakeholder investment in a future governed by parties sympathetic to construction growth. It’s a form of industry-wide lobbying, with money as the lever: by donating to National (and NZ First), the construction ecosystem helped ensure that their preferred projects and deregulations stayed high on the political agenda.

Policy Link/Outcome: The payoff for these donors is apparent in the early actions of the government. One flagship policy, the Fast-Track Approvals Act, was designed to accelerate consenting for exactly the kinds of large projects these companies work on. This law essentially removes red tape for big developments, directly benefiting both developers and the contractors who build the projects. In fact, as noted elsewhere, some fast-tracked projects were linked to donors – reinforcing perceptions of a quid pro quo.

Moreover, the government’s commitment to spend billions on new transport infrastructure translates into concrete opportunities for these donors: tenders for construction firms, supply contracts for materials providers, and so on. While formal procurement processes prevent outright favouritism, the political climate now strongly favours construction expansion, which is exactly what this donor bloc wanted.

Their financial support helps secure them a seat at the table – through access to ministers, invitations to advisory groups, or informal influence in policy development. This case is thus about sector influence writ large. It wasn’t just one company seeking a single favour; it was an entire network of industry players collectively backing the politicians who would champion their sector.

The result is a government unabashedly focused on infrastructure building, to the applause of those positioned to profit. The risk, of course, is that public policy may become overly aligned with the construction industry’s interests – potentially at the expense of rigorous environmental oversight, prudent budgeting, or alternative investments (like maintenance or social infrastructure). In summary, the construction ecosystem’s donations vividly demonstrate how money can unite an industry and shape a policy agenda, highlighting the importance of transparency and vigilance to ensure that the public interest isn’t subsumed by a well-funded private interest.

4.7 Case study: The Loopholes – How the law facilitates obscurity

Even with the new transparency rules, the 2024 returns demonstrate how sophisticated donors can use legal loopholes to obscure the full scale and source of their contributions. These are not theoretical weaknesses; they are actively exploited techniques.

4.71 Donation splitting

In 2020 rogue National MP Jami-Lee Ross alleged that the National Party accepted large donations that were split across multiple “sham donors” to remain below the disclosure limits (RNZ 2020). In general, this practice involves breaking a single large donation into multiple smaller tranches, often through different but related entities, to make the total contribution appear smaller or, under the old rules, to stay below the disclosure threshold entirely.

The rules changed in 2023, with the threshold for donation declaration reduced from $15,000 to $5000. It’s not clear that all donors were aware of this change, with some donations appearing to be made as if they were configured to avoid breaching the $15,000 threshold.

Here are the four most overt examples from last year:

Billionaire Graeme Hart donated $50,000 to Act personally, while his 100%-owned company, Rank Group Ltd, separately donated $50,000 to New Zealand First. In the public returns, there is nothing to link these two substantial donations from the same ultimate source.

Three companies controlled by property developer Yuntao Cai — Precise FTD GP Limited, Precise Homes Ltd, and North Harbor Development Limited — donated a combined $36,338 to the National Party. The donations were made as three separate payments, all of which would have been below the old $15,000 disclosure threshold.

The Brady family of Ardmore split their support into a personal donation by Donnabella & Daniel Brady ($10,000) and another $10,000 via their company (Mahuraki/Ardmore Quarries LP). Individually, each $10k wasn’t remarkable, but together the couple effectively gave $20k to National while appearing as separate entries. This allowed them to double their impact without triggering higher scrutiny, since each portion on its own was relatively modest.

Three firms directed by Matthew Walsh have been able to make coordinated donations totalling over $52,000 to the National Party, via professional firm Baker Tilly Staples Rodway Auckland Limited. This is an evolution in political financing. This pattern demonstrates a move towards professionally managed political giving, where donations are treated as a formal component of a corporate or investment strategy, administered by accounting firms to create a layer of professional distance and administrative efficiency.

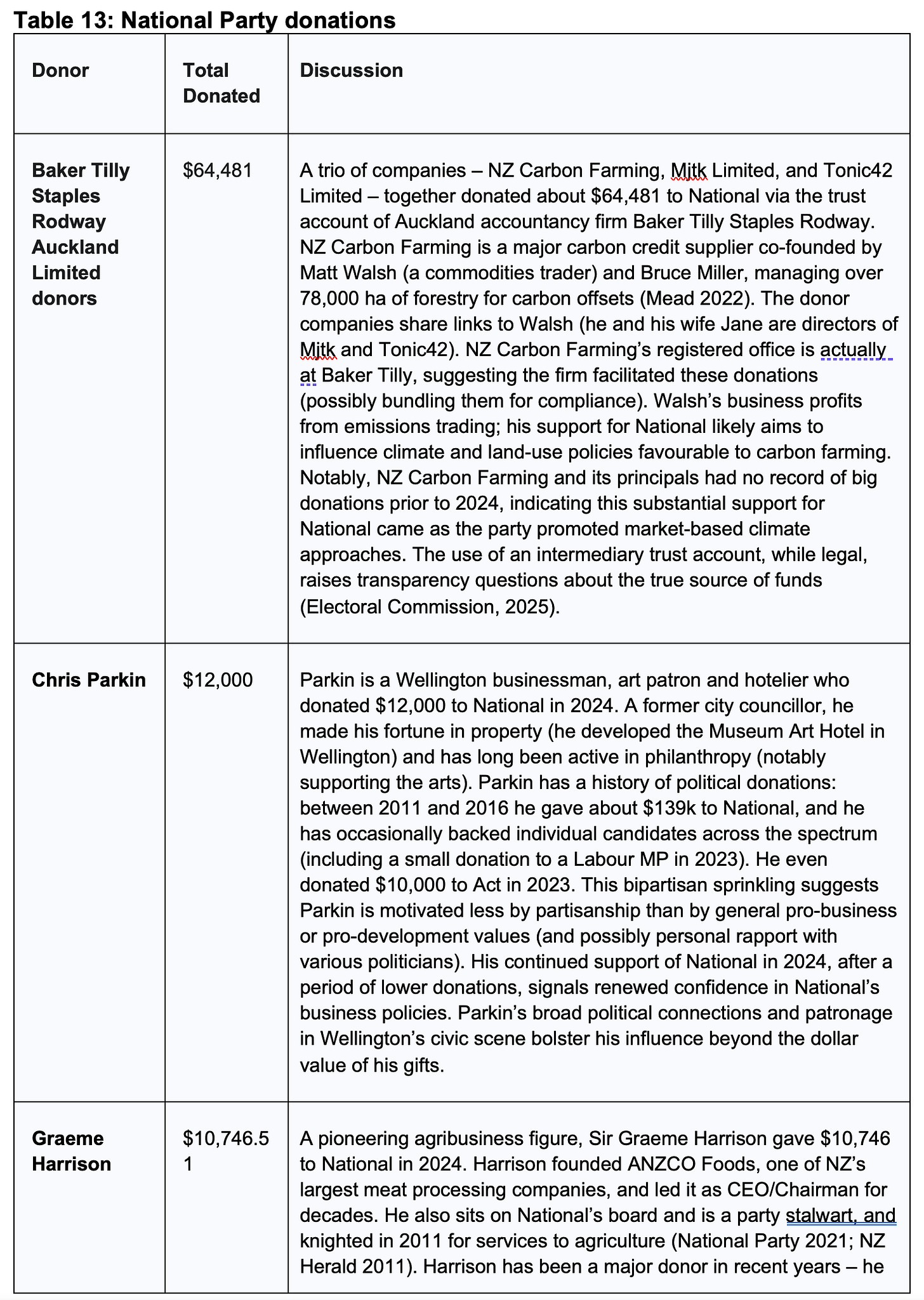

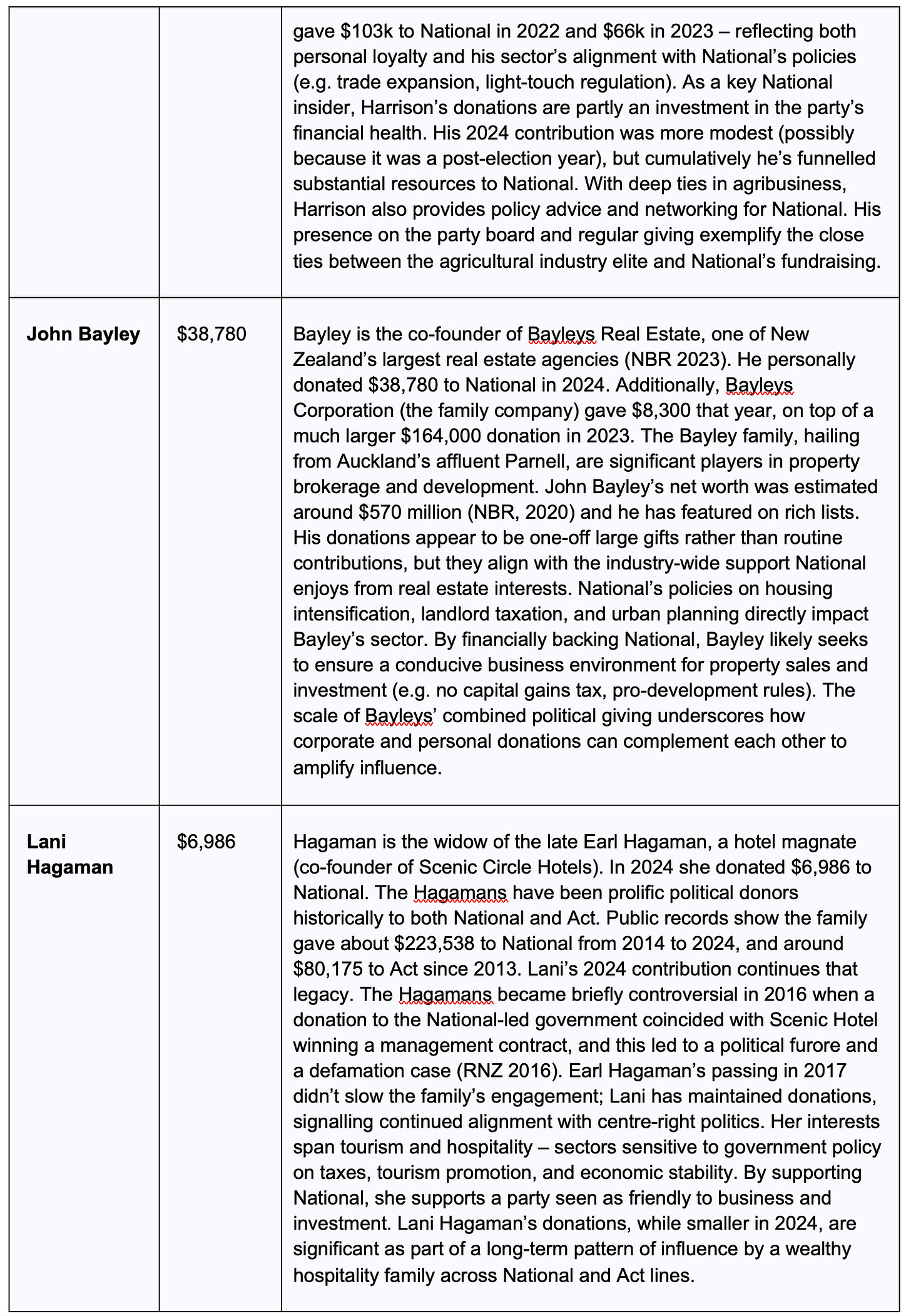

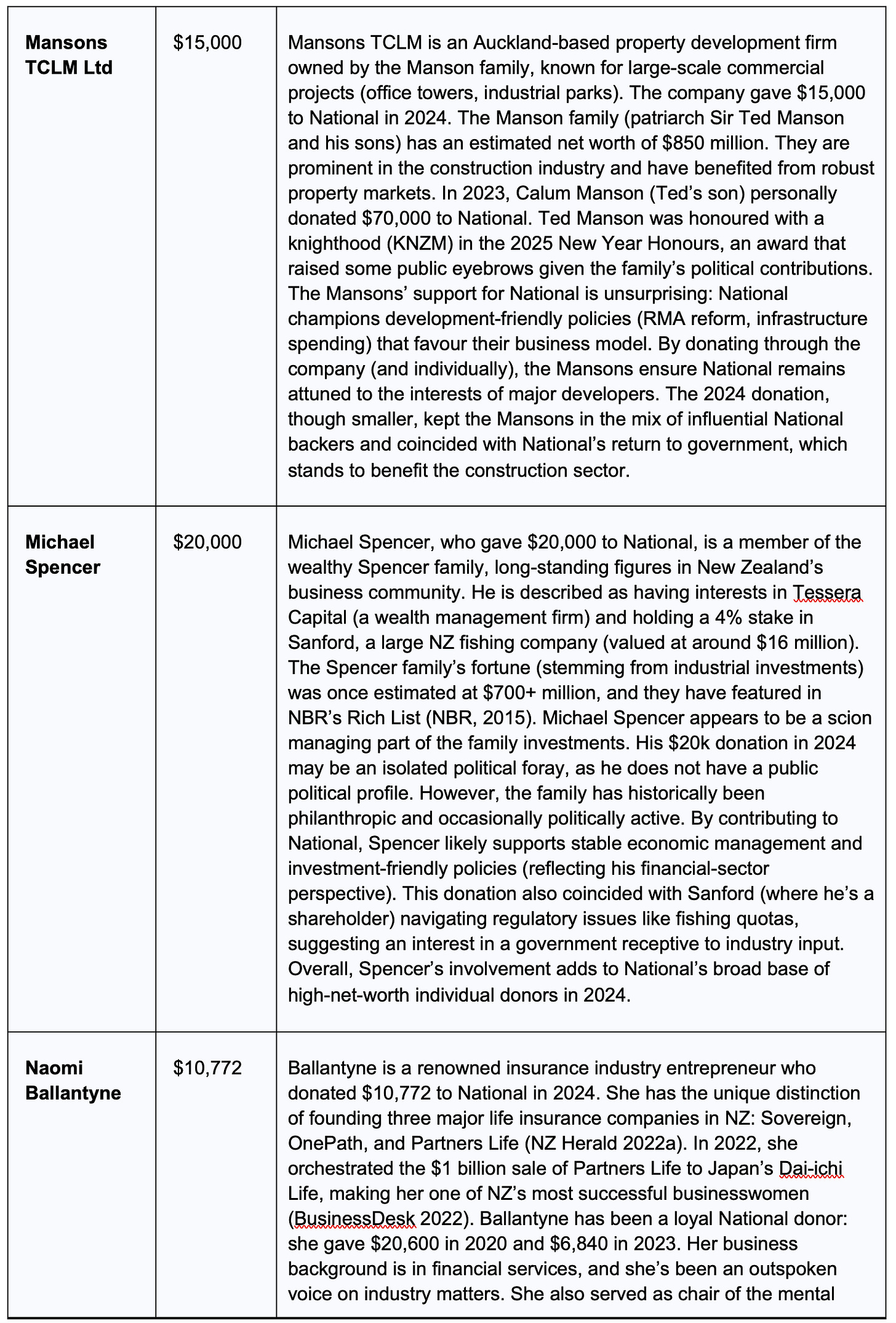

Section 5: National Party donations

5.1 Summary

As the lead governing party, National amassed nearly $4.9 million in declared donations – by far the largest war chest of any party. This money came overwhelmingly from wealthy individuals and corporations, cementing National’s reliance on big-ticket donors.

Property developers, construction firms, agribusiness magnates, and financial services executives dominate the donor list, reflecting National’s deep ties to corporate New Zealand. A significant pattern is apparent: the sectors that bankrolled National’s election campaign are the very sectors poised to benefit from its policy agenda. While this support energised National’s return to power, it also raises clear influence risks, as many donations came from entities with a direct stake in government decisions.

Moreover, several integrity flags emerge in National’s fundraising, including sophisticated donation-splitting techniques, opaque trust contributions, large in-kind donations, and even an auditor’s warning that not all funds may have been fully accounted for (BDO 2025). In short, National’s donor profile illustrates both the clout of concentrated private money in our politics and the potential vulnerabilities that come with it.

5.2 Sectoral and geographic clusters of donations

Big donors and sectoral patterns: National’s financial backing reads as a who’s who of the business elite. Longtime party patrons feature prominently. For example, the late John Wares (former Nelson branch chair) and his wife Irina gave a combined $346,000 to National, making them the party’s largest benefactors. Real estate baron Garth Barfoot (director of Barfoot & Thompson) continued his decade and half-long support with major contributions (over $270,000 donated since 2010).

National also drew on a new generation of mega-donors such as billionaire Nicholas Mowbray, co-founder of Zuru, who along with his family poured $400,000+ into National/Act coffers over 2022–2023. The pattern is clear: National’s top donors are predominantly high-net-worth businessmen, often with interests in property, finance or primary industries, who can write five- or six-figure cheques.

Beyond individual tycoons, entire industry blocs underpin National’s fundraising. The property and construction sector stands out as National’s financial backbone. Property developers and investors large and small – from Auckland moguls to regional builders – pepper the donor roll. In many cases their giving aligned with National’s pro-development platform. For example, Russell Property Group director Brett Russell donated $35,000 personally (with another $12,000 via his company) shortly after his 2,700-home Beachlands housing project was approved for fast-track consenting.

Likewise, National received major contributions from the wider construction ecosystem, not just developers. A leading contractor, 3EYES Construction Ltd, gave $23,650, while raw materials supplier Manukau Quarries LP chipped in $10,000 (matched by an equal sum from its owners on the same day), and heavy equipment manufacturer Transport Trailers Ltd added over $6,000.

These donors span the supply chain (builders, quarry operators, engineering firms) all backing a party promising a multi-billion-dollar infrastructure program. It suggests a broad coalition of construction interests investing in a government that has promised to “build roads of national significance” and streamline development approvals.

Indeed, Case Study 4.6 (above) illustrates how this sector’s donations and National’s policy agenda align. In total, companies and individuals linked to projects in the new government’s fast-track consenting regime contributed over $180,000 to National and its partner NZ First last year (Hancock 2025a). Such temporal proximity between donations and policy outcomes (e.g. expedited consents) heightens the risk – or at least the perception – of a quid pro quo.

National’s donor base extends into other key sectors of the economy as well. The agribusiness and primary industries were significant contributors, consistent with National’s rural support. Prominent farming enterprises and food processors appear among mid-tier donors (e.g. Woodhaven Gardens with $5k, WoolWorks NZ $7.8k), alongside agricultural suppliers and transport firms that rely on rural growth. These donors have a vested interest in policies on water use, environmental regulation, and regional development – areas where National’s approach is seen as more industry-friendly.

Similarly, National drew donations from the manufacturing and tech sector, such as Tiger Brokers (NZ) Ltd which gave $49,665. Tiger is a fintech brokerage, and its near-$50k contribution suggests an expectation of influence over financial market regulations, fintech innovation policy, and taxation settings affecting investors.

Another notable donor, David John Ryan (the managing director of Aalto Paints), contributed $23,629, bringing a rare domestic manufacturing voice into National’s funding mix. His interests are likely to lie in trade policy, industrial training, and procurement rules that could affect local manufacturers. The picture that emerges is a broad coalition of business interests rallying around National – from real estate to finance to farming – each arguably “investing” in a favourable policy environment for their industry.

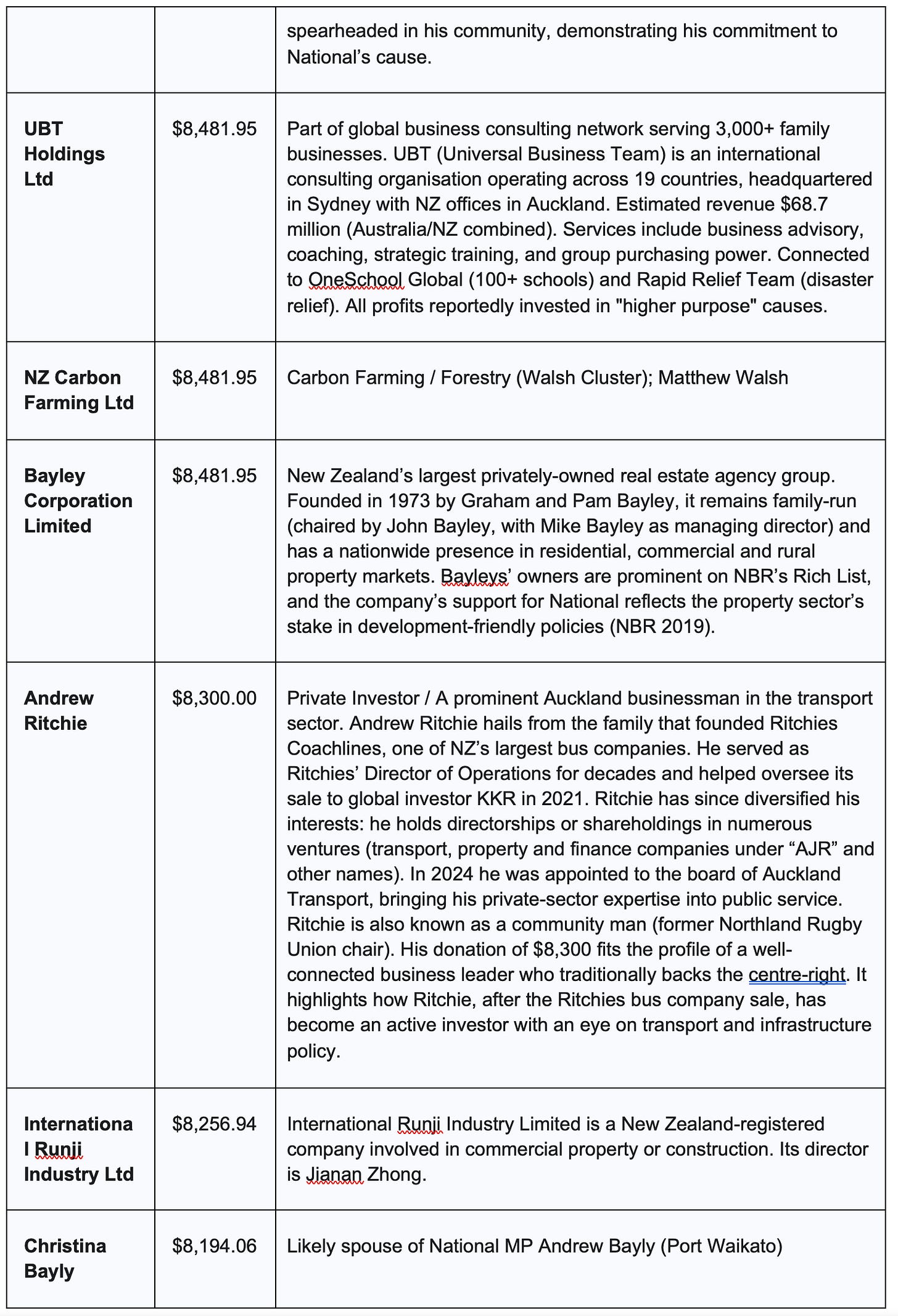

5.3 The Rise of diaspora donor networks

One striking development last year was the rise of diaspora business networks as a component of National’s funding. The party attracted numerous mid-sized donations (often $5k–$15k) from New Zealanders of Chinese and Indian heritage, indicating organised support from migrant entrepreneur communities. For example, Ranjay Sikka (Slumberzone bedding and property ventures) gave $12,354, Wenbin Yao (property investor) about $11k, and Divay Shrivastava (IT/health consultant) $11k.

Collectively, dozens of donors from these communities contributed significant funds. This trend reflects a strategic alignment: National’s platform of tougher law-and-order, pro-business immigration settings, and trade-friendly foreign policy resonated strongly with many migrant business owners. Their donations can be seen as a rational bet on a party promising stability and growth, and they underscore how National has broadened its financial base beyond the traditional Pākehā business elite. In essence, a new constituency of diaspora capital has joined the old money in backing National, adding a multicultural dimension to the party’s corporate fundraising machine.

5.4 Risks of influence (quid pro quo)

Influence risks and integrity flags: Given National’s donor profile, concerns naturally arise about policy capture and ethical boundaries. Many of National’s biggest donors are not just passive supporters but interested parties with direct stakes in government decisions. The Fast-Track consents case is the clearest example: donors like Brett Russell stood to benefit immediately from National-led policy, and indeed saw their projects accelerated (Hancock 2025a).

Similarly, the carbon farming case (Case Study 4.5) reveals how a cluster of donations from NZ Carbon Farming (via three Matthew Walsh-controlled companies) totaling over $52,000 was timed as the new government signalled an overhaul of Emissions Trading Scheme rules. NZ Carbon Farming’s business model (planting forests to earn carbon credits) is acutely sensitive to ETS policy settings. The sizeable donation by Walsh’s group, split across multiple entities, can be seen as a bid to ensure the company’s voice is heard in pending climate policy reforms.

National’s early rhetoric on “pragmatic” climate policy (focusing on economic growth over punitive emissions costs) certainly aligns with this donor’s interests. While no illegality is implied, the optics of such contributions are problematic: they create an expectation that access and influence can be purchased on matters of public policy. National’s reliance on big-money backers thus poses a standing risk of conflicts of interest, where decisions might be – or appear to be – shaped by who writes the cheques.

Beyond specific policies, systemic integrity issues emerge in National’s 2024 return. An obvious red flag is the presence of donation-splitting and obscured donor identities. For instance, the Matthew Walsh cluster mentioned above was carefully structured: three corporate donations (of $20k, $17k, $8.5k) all came from the same address (an accountancy firm) and ultimately from the same source. By parcelling out over $50k through different entities, this donor stayed under certain per-donor reporting radars while still exerting outsized influence.

Likewise, National received a $50,000 contribution from the Canterbury Nationalist Trust, an entity linked to former MP Jim Gerard. Only insider knowledge connected Gerard to the trust. Without a full list of trustees and beneficiaries, the ultimate source of this $50,000 remains partially obscured.

These examples show how trusts and corporate vehicles can obscure the true source of political funds – a loophole that National’s donors have not hesitated to exploit. Another example in the wider coalition was billionaire Graeme Hart, who last year donated $50k to Act personally while his 100%-owned company gave $50k to NZ First, effectively halving the visibility of his support. Such practices undermine transparency: the public may see “two $50k donations” instead of recognising one $100k influencer. The Integrity Gap widens when the wealthy can so easily conceal their full political spending.

National also accepted donations last year from a property developer who had previously been fined $123,000 in 2019 for breaches of the Overseas Investment Act. Yuntao Cai, an Auckland developer had bought a Birkenhead property for development while technically classified as “overseas persons,” violating the rules (Overseas Investment Office 2019; RNZ 2019). And in 2024 Cai donated $6,988 to National via his company Precise Homes Ltd. This raises an integrity concern: National accepted money from an individual who previously flouted NZ’s investment laws. While the donation is legal, it “looks bad” from an optics perspective as it exemplifies how a person penalised for trying to circumvent NZ law is now funding a major party.

5.5 Non-monetary contributions

National’s 2024 disclosures also highlight the role of non-cash donations as an underappreciated influence channel. The party’s official return shows it received roughly $193,000 worth of “Non-monetary Party Donations” (i.e. goods and services provided for free). This included pro bono professional services, discounted advertising, venue hire, and other in-kind support that saved the party significant money. In fact, these in-kind contributions made up nearly 4% of National’s total donations by value.

While perfectly legal and disclosed in aggregate, they present an integrity challenge: such contributions often fly under the radar and can create subtle debts of gratitude. A law firm quietly providing free legal counsel or a PR agency managing a campaign at no charge might gain privileged access and influence within the party in ways the public cannot easily trace. National’s campaign, for example, benefited from almost $200k of services it didn’t have to pay for, freeing up cash for other uses. The specific donors of these services are listed among monetary donors, but their in-kind nature means the real currency of influence may be expertise and insider access, not just dollars.

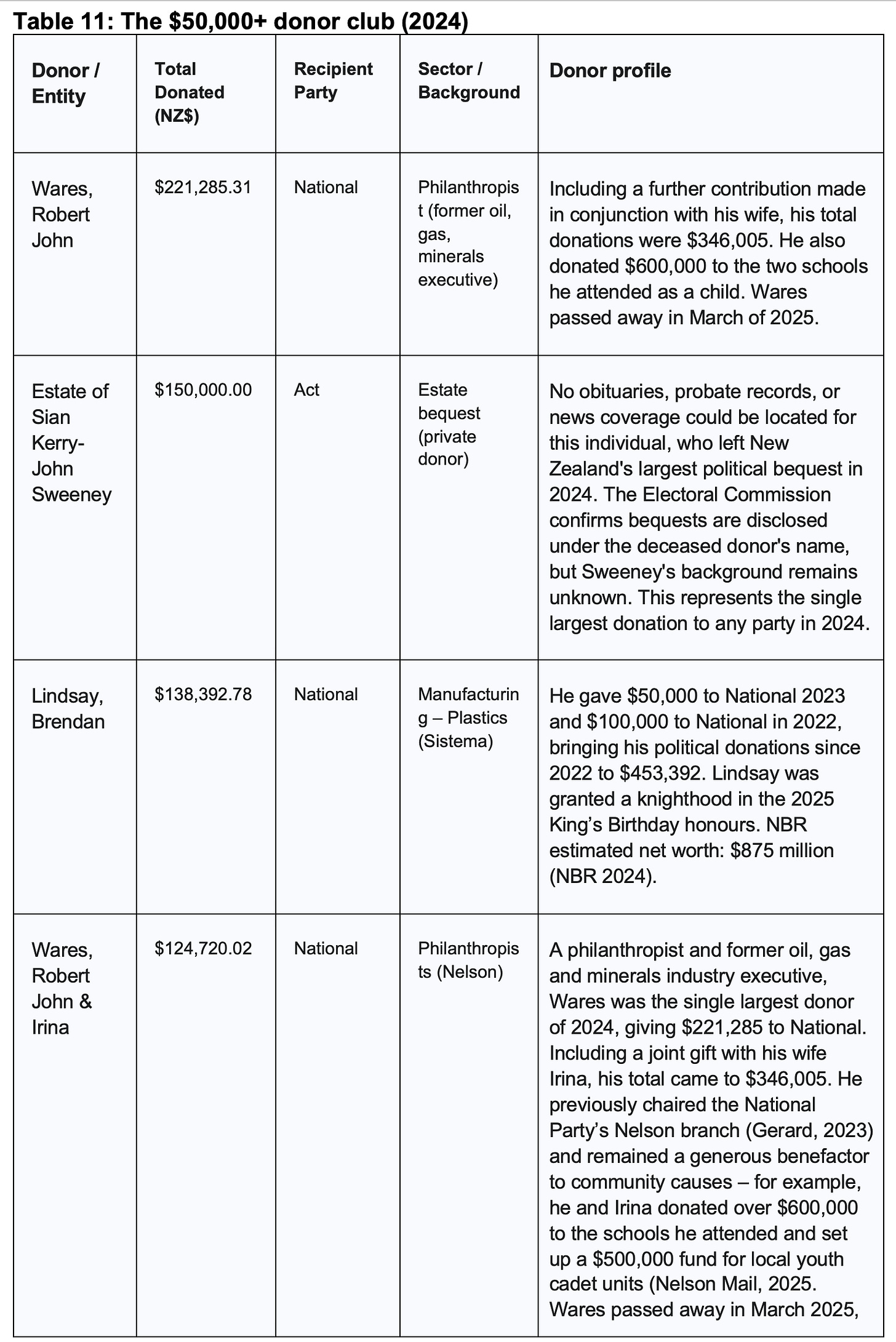

5.6 Compliance issues