The bodies are being recovered. The memorial services are being held. The inquiries are being announced. But as New Zealand moves from the immediate horror of the Mount Maunganui tragedy into the familiar ritual of official review, a harder set of questions is emerging. Not just “what went wrong at 9.30am on January 22?” but “why does this keep happening?” and “what, exactly, is the plan?”

The answer to that last question, as far as anyone can tell, is: there isn’t one.

Labour’s emergency management spokesperson Camilla Belich put it plainly this week: there has been a “rinse-and-repeat cycle” in New Zealand of experiencing a disaster, doing a review of what went wrong, and announcing we need to change the rules. Belich said: “We can’t keep that going indefinitely. We do need to draw a line in the sand and say we’re going to implement a different regime.”

She’s right. But the question is whether anyone in power is actually prepared to do that, or whether Mount Maunganui will become another entry in the long catalogue of preventable tragedies followed by narrow inquiries and incremental tinkering.

The Week before the disaster

Consider what happened on January 14, exactly one week before the fatal landslide at Mauao. According to Newsroom’s Fox Meyer, Forestry Minister Todd McClay wrote to Gisborne District Council with bad news. The council had spent months preparing a comprehensive business case for land use transition in Tairāwhiti, one of the hardest-hit areas from Cyclone Gabrielle. They asked for $359 million over ten years from central government, which they were prepared to match with $240 million from landowners, businesses and community groups. The requested amount was less than the losses suffered by the primary sector alone in the area during 2023 and 2024.

McClay’s answer? New Zealand’s “challenging fiscal position” meant the Government couldn’t afford it.

Then two weeks later, on January 28, McClay issued a press release with a familiar top line: “Significant rainfall, flooding, slips, and hailstorms have caused damage to farms, crops, and rural infrastructure.”

This is New Zealand’s disaster management strategy in microcosm. Reject the investment in resilience. Wait for the next catastrophe. Express concern. Repeat.

Eighty percent on recovery, eight percent on readiness

The pattern is not anecdotal. It is now documented. Fox Meyer also reported this week about a 2025 investigation by consulting firm Sapere, commissioned by Insurance Australia Group New Zealand, that found that just 8 percent of the $41 billion spent by the government on natural hazards since 2010 went to readiness or risk management measures. Recovery efforts accounted for 80 percent of the expense, with a further 12 percent spent on response.

Canterbury University adaptation expert Professor Bronwyn Hayward summarised the problem for RNZ: “Our key problem is that we tend to respond to every disaster in an ad hoc way. And we’re treating every disaster individually.”

This is not news. Emergency management experts have been making the case for resilience investment for decades. Official advice on the current Emergency Management Bill states that international evidence suggests every dollar spent on preparedness saves four dollars spent on recovery. Yet we keep doing the opposite.

Mike Hosking, not usually given to radical critiques of market mechanisms, made the point even more bluntly this week. The Government’s answer to repeated disasters, he noted, is more band-aids rather than prevention. He asked the obvious question after talking with Chris Penk, Mark Mitchell, and Christopher Luxon: “What’s the big picture? There is one, they reassure us. Not sure of a timeframe, which is political speak for ‘it’s on the never-never’.”

He went on: “Build it, watch it get destroyed, patch it up, watch it get destroyed and patch it up? It’s not my favoured plan.” When Mike Hosking and Bronwyn Hayward are making the same critique, perhaps it is time to listen.

Broken New Zealand

The Mount Maunganui tragedy fits a broader pattern I have been writing about in numerous columns recently: a country that has systematically lost the capacity for long-term planning, serious public investment, and collective action on hard problems.

Danyl McLauchlan, writing in the Listener this week, connected the dots with characteristic bluntness. The Coalition Government’s decision to “quietly abandon the mechanisms for delivering on most of our climate commitments” and roll back the policy infrastructure that National and Christopher Luxon “proudly agreed to in opposition” is, he argues, “entirely rational” from a short-term political perspective.

But it “locks us into a future in which our storms, wildfires and droughts get steadily worse, our bridges crumble into rivers, people drown in torrents of mud, insurance costs keep spiralling up and our councils go bankrupt.”

The abolition of the $6 billion National Resilience Plan in Budget 2024, with $3.2 billion returned to the Crown to help fund tax cuts, is the signature example. Labour established that fund after Cyclone Gabrielle precisely to address the chronic underinvestment in resilience. The current Government dismantled it.

McLauchlan asks the question that should haunt the political class: “So what is New Zealand’s climate strategy?” His answer: “At the moment it is to pretend to fulfil our obligations while doing nothing to deliver on them.”

Since we are obviously locked into a warmer, more destructive climate, building resilience should be a high priority: upgrading water infrastructure to cope with heavy rainfall, managed retreat from zones at high risk from floods and landslides. “But that, too, has been dismantled” says McLauchlan.

When Insurers become the planners

If government will not make the hard decisions about where it is safe to live and build, someone else will. Increasingly, that someone is the insurance industry.

This week AA Insurance stopped offering new home insurance policies in Westport because of the town’s flood risk. As the Herald editorial today warns: “Westport won’t be the only community to face this harsh reality; several towns and neighbourhoods will face similar challenges in the years ahead.”

The editorial framed the stakes clearly: “New Zealand is quickly approaching a climate crossroad that is on the verge of being washed away... If, at this junction, we continue down the same road of reaction, then some communities will face the prospect of being abandoned. If not by their people, then by those holding the purse strings, the insurance companies and the Government.”

This is a failure of governance. When private insurers are effectively deciding which communities are viable and which are not, we have outsourced one of the most fundamental questions of collective life to actuarial tables.

Councils, meanwhile, are caught in an impossible position. They are under pressure not to label risky land because landowners become aggrieved about its impact on property values and take legal action, as has happened repeatedly with coastal hazards. So official LIM reports note whether there have been slips (an incontrovertible fact) but often do not include modelled risk assessments. The hard work of determining where it is actually safe to live has been left, by default, to insurance underwriters.

As the Herald put it: “If we don’t make the difficult decisions then our insurers will.” The problem is that insurers acting as the “shadow government”, making their land-use and risk decisions based on profit margins, not public good or equity.

What kind of inquiry?

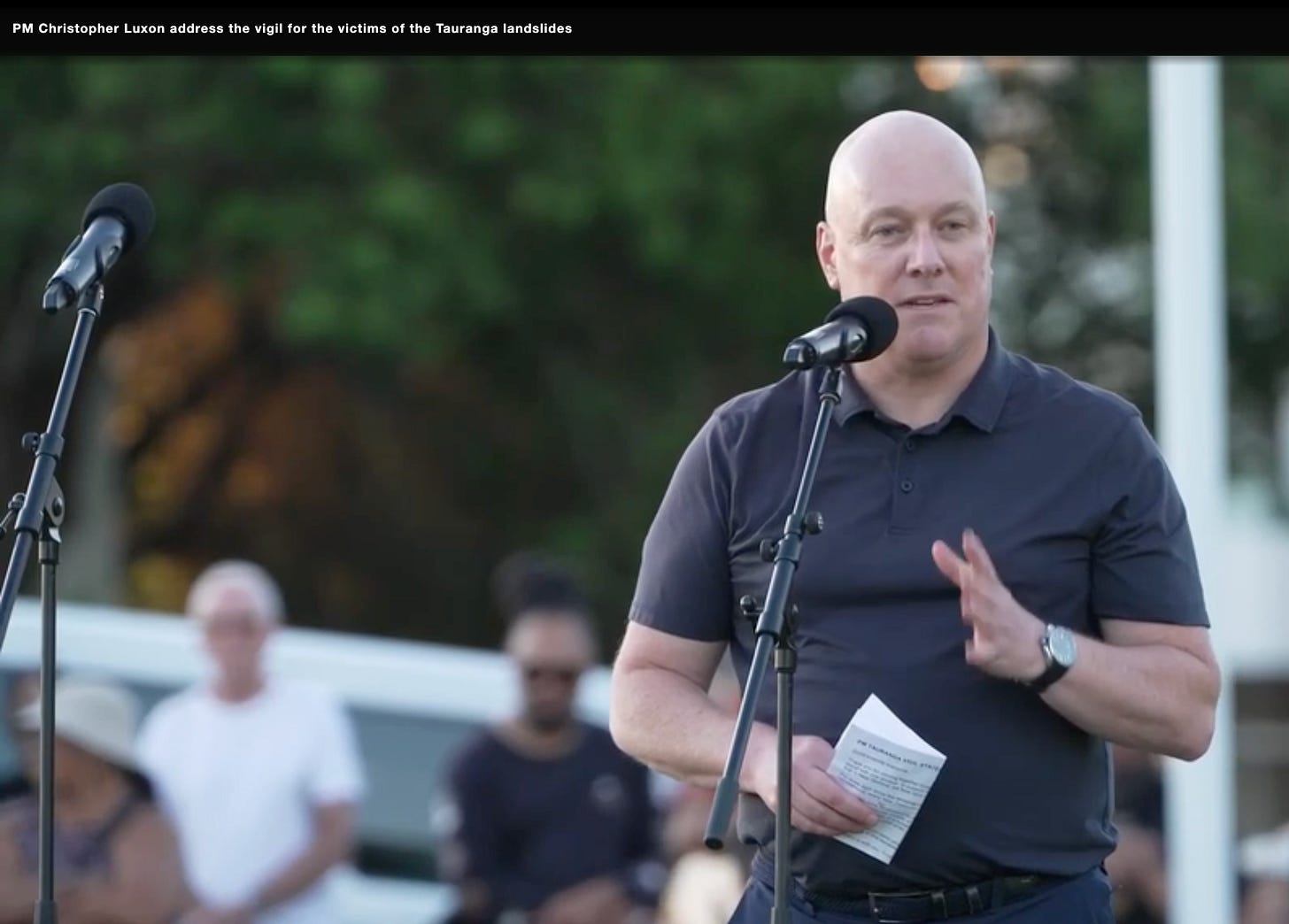

Multiple investigations are now underway or announced: Police examining potential criminal liability, WorkSafe investigating duty of care obligations, the coroner preparing an inquest, and Tauranga City Council commissioning its own independent review. The Prime Minister has signalled a “strong case” for a government-level inquiry.

But what kind of inquiry? And with what scope? Former minister Lianne Dalziel, who led Christchurch’s recovery from the earthquakes, has argued strongly for a single, comprehensive approach: “We don’t need multiple inquiries as happened with the severe weather events of 2023. This one needs to be joined up and completely independent.” She emphasises it “needs the ability to compel evidence, which is why the Government needs to be involved in setting it up.”

Peter Dunne has gone further, calling for a Royal Commission of Inquiry comparable to the Christchurch earthquakes investigation. Such a commission, he argues, “should be charged with looking at all aspects of the event, including the adequacy of the Council’s monitoring and regulatory procedures beforehand and the effectiveness and co-ordination of the post-event emergency response.”

Crucially, Dunne says a Royal Commission “could also look beyond the specific circumstances of Tauranga and consider whether the same potential risks exist in other parts of the country.”

This is the key point. A narrow inquiry focused on who wrote which email at 5.47am will produce a narrow set of operational recommendations. It will not ask why, twenty years after geotechnical engineers told Tauranga Council not to allow buildings in landslide runout zones, a campground full of families still sat directly in the firing line. It will not ask why hazard maps stop at ratepayer properties and do not cover tourists. It will not ask why the $6 billion resilience fund was abolished, or why councils are expected to manage climate risk on balance sheets never designed for it.

Imagine something different

Basher offers a more hopeful vision: “Imagine, as a result of the Mauao tragedy, someone high in Government wakes up to the big picture: that we have too many disasters and suffer too high a cost from them, in lives and financial losses.”

He proposes a radical institutional response: “a new Ministry of Risk and Loss Reduction... to get a better grip on New Zealand’s outsized disaster risks.” Strategic vision. Political leadership. Serious resources. “Fewer fatalities! Billions saved!”

Is this utopian? Perhaps. But consider the alternative. As Basher notes, “the economy bleeds billions of dollars as a result of disasters, year after year, yet this negative side of the economic ledger is ignored.” He notes that the words “disaster risk” do not appear in the current planning bill, environmental bill, or their explanatory briefings. We are legislating as if the last decade of floods, fires, and landslides never happened.

The Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill, designed to replace the Resource Management Act, continue this emphasis on “enabling housing, infrastructure and productive activity”, with environmental limits treated as secondary considerations. There are provisions for regional spatial plans over 30-year periods that will consider natural hazards, but the dominant legislative direction is clear: speed up development, reduce barriers, enable growth.

Nobody opposes housing or infrastructure in principle. The question is whether we are building the right things in the right places with proper attention to the risks. And the evidence suggests we are not, because the political system rewards short-term economic activity over long-term resilience planning.

Treasury has warned there is an 80 percent chance New Zealand will experience another Gabrielle-scale event within the next 50 years. The 2023 cyclone killed 11 people and the recovery bill for all the 2023 storms caused up to $14.5 billion in damage. Climate scientists tell us storms are becoming more frequent and more intense. Professor James Renwick recommends a national survey of all camping grounds to assess exposure to extreme weather. Dr Tom Robinson says we need “a really serious conversation nationally and internationally about how we’re going to manage the risks we’re faced with.”

Where is that conversation? Where is the national framework for climate adaptation that Renwick and others have been calling for, instead of the current piecemeal council-by-council approach? Where is the serious discussion of managed retreat from the most vulnerable areas – the conversation that everyone knows is coming but no politician wants to start?

My main point is that establishing what failed at Mount Maunganui is not enough. The harder question – the one that cuts to the heart of New Zealand’s governance crisis – is why this keeps happening. Why do we lurch from disaster to disaster, conducting forensic inquiries into operational failures while never examining the policy choices that guarantee the next tragedy? Why does a nation that knows it sits on geologically unstable ground, in a warming climate that is intensifying storms, continue to govern as though the future will take care of itself?

The answer is that Mount Maunganui is not actually an aberration. It is a symptom of systemic failures in how New Zealand approaches risk, planning, and climate adaptation. This is “Broken New Zealand” in action: a political system that prioritises short-term economic gains over long-term resilience, that systematically dismantles expertise, that talks earnestly about climate adaptation while cutting the funding for it, and that conducts narrow inquiries after each disaster without addressing the policy failures that created the conditions for harm. Until politicians confront this pattern, they are making policy choices that accept more preventable deaths.

An Election year test

This is an election year. The disaster at Mount Maunganui, and the broader summer of floods and slips across the North Island, presents a test for every party.

Will anyone make disaster resilience and climate adaptation a central election issue? Will anyone commit to restoring serious funding for hazard mitigation? Will anyone propose the kind of institutional reform that the evidence demands? Will we get a commitment to a Ministry of Risk and Loss Reduction, a proper national adaptation framework, and a genuine shift from reactive recovery to proactive prevention?

Or will we get the usual pattern: solemn words at memorial services, a narrow inquiry, some operational recommendations, and then back to business as usual until the next preventable tragedy?

The politics of this summer are already set. The only question is whether we are honest about what they reveal, and whether we demand more than the familiar cycle of disaster, review, and forgetting.

Basher asks the right question: “What better legacy could there be for those who lost their lives last week?”

Six people died at Mount Maunganui. Two more died in Pāpāmoa. They died because New Zealand, despite decades of warnings, has no coherent plan for managing the intersection of climate change, land use, and disaster risk. Fixing that would be a legacy worth fighting for.

The question is whether anyone in power has the will to try.

Dr Bryce Edwards

Director of the Democracy Project

My previous columns on this topic:

Bryce Edwards (Democracy Project): Shock turns to anger at Mount Maunganui

Bryce Edwards (Democracy Project): How Authorities failed campers at Mount Maunganui

Further Reading and Sources: